Why the Farmers in India are Up in Revolt

Farming turning increasingly unviable across vast swathes of India, and the Narendra Modi-led government not delivering on the BJP’s election promise to “make agriculture rewarding” lie behind the massive protests that have rocked several BJP-ruled states in the recent weeks.

In the run-up to the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP vowed to ensure a prosperous future for the country’s peasantry. One major item in its manifesto was that steps would be taken to enhance the profitability of agriculture by ensuring a minimum of 50 per cent profit over the cost of production as recommended by the National Commission on Farmers headed by MS Swaminathan. In the same vein, Prime Minister Narendra Modi pledged last year to “double the income of farmers” by 2022.

However, the farmers were in for a rude awakening. While the promised remunerative prices for crops were nowhere to be seen, demonetisation dealt a heavy blow by crippling trade in agricultural commodities at a time of good harvests. As a result, the recent months saw colossal crashes in the prices of a large number of crops. Forget 50 percent profit over the cost of production, the farmers were forced to sell their produce at well below the minimum support price and the cost of production, pushing them deeper into debt. For example, the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for moong for the Kharif 2016-17 season was Rs. 5225 per quintal, while the average price in Madhya Pradesh on 6 June 2017 was Rs 3677, almost 30 percent lower than the MSP.

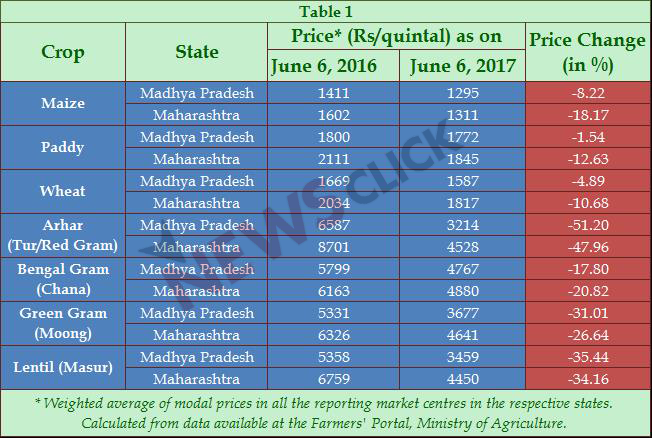

Table 1 shows the prices in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra of seven major crops on 6 June 2017, the day of the police firing in Mandsaur, Madhya Pradesh which resulted in the death of 5 farmers, compared to the prices that prevailed one year ago.

Pulses were severely hit – price crashes to the tune of about 50% for Arhar (tur/red gram), 35% for lentil (masur), 17-20% for Bengal gram (chana), and 26%-31% for Green gram (moong) have been nothing short of catastrophic for the farmers. Cereals such as wheat, paddy and maize also saw prices declining sharply. (Note that what we have here are nominal prices. The fall in real prices (which take into account inflation) is steeper.)

The peasant protests gathered further strength following the Mandsaur killings. The farmers demanded debt waiver and fair prices for their crops – that is, prices which are 50% above the cost of production. Amidst country-wide outrage and stormy agitations, the central government announced Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for crops, for the Kharif 2017-18 season. However, this is unlikely to be sufficient to satisfy the peasantry, for three main reasons.

First, the announcement of the MSPs need not mean that the farmers will be able to sell their crops at that price. If the government does not ensure that crops are procured at the support price through purchasing centres, and if the market conditions are unfavourable, the farmers can very well end up being forced to sell their crops below the MSP. Under such circumstances, the MSPs declared by the government remain merely on paper.

Second, the estimates of Cost of Production are themselves outdated. The Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) – which makes the MSP recommendations – uses cost estimates that are generally available with a time lag of three years in case of kharif crops. The Cost of Production estimates of 14 crops for the kharif season 2017-18 are projections based on actual estimates for the three years from 2012-13 to 2014-15. The CACP’s report shows that in most cases, the Cost of Production projections by the State governments are significantly higher than the projections of the CACP. For instance, the cost of production projections of the CACP for paddy for 2017-18 are Rs 1495 per quintal in Andhra Pradesh and Rs 1656 per quintal in Odisha, but the State governments' projections are Rs 1866 (Andhra Pradesh) and Rs 2344 (Odisha). Farmers’ organisations attest that the State governments’ calculations of the Cost of Production are closer to the calculations of farmers.

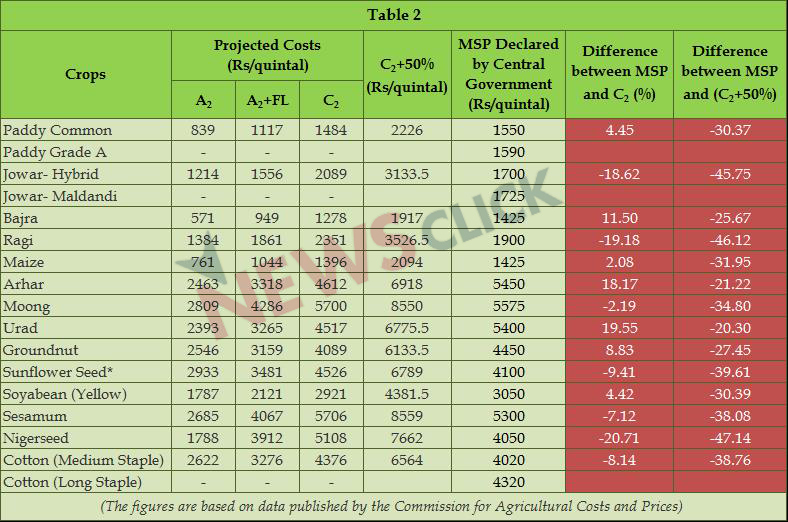

Third, the MSPs announced are too low compared to what the farmers have been demanding. The MSPs are lower than the cost of production, especially if the comprehensive costs (termed C2 by the CACP) including imputed value of family labour, imputed rent and interest on owned land and capital are taken into account. (The other two measures for Cost of Production used by the CACP are A2, which covers actual paid out cost, and A2+FL, which covers actual paid out cost plus imputed value of family labour.)

As Table 2 shows, the MSP declared by the central government is lower than the cost of production (C2) for jowar, ragi, moong, sunflower seed, sesamum, nigerseed and cotton (medium staple).

The column titled ‘C2+50%’ shows the prices as per the Swaminathan Commission formula when C2 is taken as the cost of production. As can be seen from the last column, not a single crop’s MSP comes anywhere close to what the farmers are demanding and what the BJP had promised.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, the peasantry’s anger against the government’s callousness has not abated. Long-time observers of the political scene in India have noted that the peasant movement that has emerged now is coming after a gap of nearly four decades. The farmers are on the move, and are preparing for country-wide agitations.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.