SC’s Reluctance on Babri Masjid Dispute Could Fuel Discord in Near Future

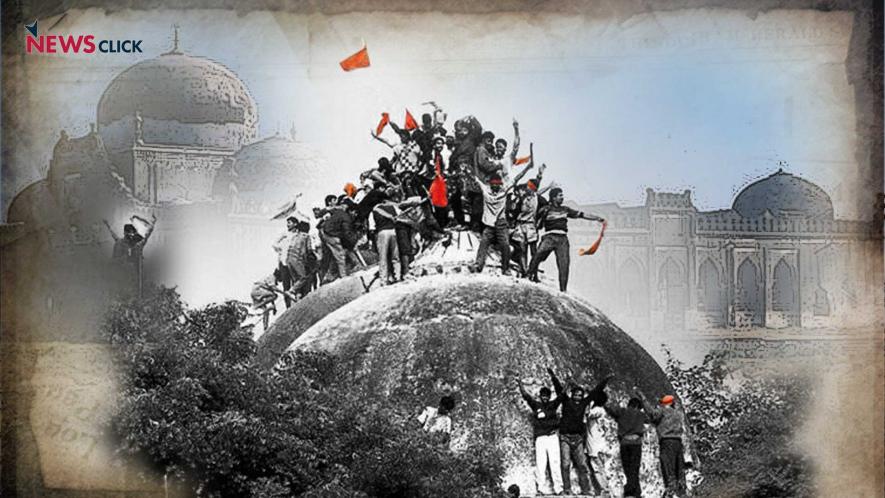

“A mosque is not an essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam and namaz (prayer) by Muslims can be offered anywhere even in open”- this observation by the majority in a constitution bench of five judges of India’s Supreme Court in a 1994 case concerning the demolition of a mosque by Hindutva forces created a maelstrom when it was delivered then, and carried the potential to stoke communal fires even now. Especially when India goes to polls in mid-2019 in a political atmosphere surcharged with partisanship and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party making it clear that Hindutva would be its decisive agenda.

In such a scenario, a 2:1 majority judgement by the Supreme Court on September 27, has led to both the Hindutva parties who fervently support the building of a Ram temple in the same place where the Babri Mosque originally stood, and the Muslim parties who are staunchly opposed to this idea, to respectively claim victory. The former have claimed that the ruling lends much credence to their long-standing demand that they have a legal right to construct the Ram temple where the 15th century mosque originally stood, while the latter have stated that they see the judgement as contributing to some “positive movement in the case”.

But the questions remain – what is the real effect of the ruling? More importantly, did the Supreme Court majority take the correct and just decision? Opinions differ.

A Fractured Verdict, and a Powerful Dissent

In its ruling, the majority declined to grant the petitioners’ prayer that the 1994 judgement be referred to a larger bench of five judges, so that the latter could reconsider it and correct what they contended was a gross error. The majority, comprising Chief Justice Dipak Misra (who retired on October 2) and Justice Ashok Bhushan held that the observation in the 1994 ruling was made only in a specific context and would not affect the adjudication of the main dispute-- that is, the appeal against the 2010 Allahabad High Court judgement which gave Hindus a greater right over that of Muslims regarding the disputed area-- it split the land between the Hindu and Muslim parties, though the main part was given to the former. A three-judge bench of the High Court had arrived at this conclusion by placing the “faith and belief of the majority-- the Hindus” on a higher pedestal than the legitimate claims of Muslims who had contended that the 15th century mosque should not have been demolished to make way for a Hindu temple, and has been subjected to much criticism.

Relying on principles of statutory interpretation, the Supreme Court majority held that the comment of Justice J.S. Verma in the 1993 ruling should be interpreted as being relevant only in the context of the government having the right to acquire land, irrespective of which place of worship stood on it. But that right of the State was always there, and was not in dispute in the case. What causes consternation is the fact that the majority, by taking, perhaps, a narrow view of the issue, might have given the Hindutva (a particularly virulent and political ideology of Hinduism) parties an upper hand in the dispute which is yet to be finally decided by the apex court.

But the focus of attention ought to be the powerful dissenting opinion authored by Justice S. Abdul Nazeer, a Muslim judge. He disagrees with the majority, and makes out a strong case for referring the matter to a larger bench, given its seminal importance in the history of Indian politics. It would be myopic, and dangerous, he said, to classify the present case as one of a title suit or a property dispute, and ignore the ramifications it has for millions of India’s Muslims and on electoral politics.

While doing this, he accepted the arguments of senior counsel Rajeev Dhavan who consistently argued that the matter has great significance in how the judiciary interprets the cardinal doctrine of secularism. He pointedly asked-- if issues like whether Hindus can use public spaces to celebrate festivals like Dusshera and hold prayers where hundreds throng, are being referred to a larger bench for adjudication, why not this particular issue? Are the religious rights of Muslims less important compared with those of their Hindu counterparts? Justice Nazeer also pointed out how the 2010 High Court judgement, which had given preference to the rights of Hindus, had been influenced in no small measure by the observation in the 1994 ruling.

Sharp Criticism, Heightened Scrutiny

Rajeev Dhavan, who is representing the majority of Muslim parties before the Supreme Court, has called the majority decision “fatally flawed” and said that the majority judgements in the 1994 and present case, respectively, in this case “have pre-emptively knocked the bottom out of the Muslim case” and that “Worse, Hindu fundamentalists are given a license to trespass into a mosque and destroy it to claim both prayer in, and ownership of the site!”

Senior Advocate Sanjay Hegde, who had once written that the temple-mosque issue would take centrestage in the 2019 national elections when the incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi would be going all out to secure a second term, and that the final verdict would leave an indelible mark on the politico-social ethos of India, said that judicial propriety and discipline required that the issue be referred to a larger constitution bench. “The majority judgement would only fuel fear and doubts in the minds not only of Muslims but also of secular Indians who repose faith in the Supreme Court’s impartiality and commitment to the constitutional ideal of secularism which is a part of the basic structure of the constitution”, he said.

Fuzail Ayyubi, who appeared from one of the parties in the matter, had written about why the Supreme Court must refer the matter to a larger bench because the 1994 ruling negates the principle of secularism, said that the apex court did good to clarify that the observation in the 1994 case would not affect the present pending matter, but could have gone further, even if it was to bolster its own image before the population and India’s minorities. He sounded guarded in his remarks, though.

With PM Modi raking up the issue of the Ram Temple and casting aspersions on the crusaders of the Muslim cause even in a speech delivered for a local election in 2017 , with legal scholar A G Noorani questioning the Hindutva parties’s tearing hurry in getting the case finally decided before the 2019 elections and stating that the Supreme Court is on trial, and the ruling BJP’s parent parent organisation’s chief and Hindutva ideologue Mohan Bhagwat boasting about the majoritarian will, it appears that India’s top court has put itself in the line of heightened scrutiny, even criticism.

Saurav Datta works in the fields of media law and criminal justice reform in Mumbai and Delhi.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.