Scotland: The Country That Almost Was

As the day dawned on 19th September 2014, an independent Scotland came close, but not as close as many thought, to becoming a reality. For now, the Union Jack will retain the blue background and white diagonal stripes that make up the Saltire or Scottish flag. The final tally of 45% Yes in favour of Independence to 55% No revealed a larger margin than opinion polls had indicated on the eve of the referendum. On the other hand, the Yes campaign got much nearer to the half-way mark than was widely believed to be likely even a few months back. In the last few weeks, the momentum was clearly with the Yes campaign but the results showed that most of the large numbers of undecided voters --- perhaps undeclared would be more accurate --- felt the risks of independence were either too high or not known well enough, and eventually voted to stay in the Union.

Anxieties tipped the scales

28 of the 32 councils voted No and many with large margins. Only Scotland’s largest and heavily working class city of Glasgow with high unemployment rates voted Yes, but only by a narrow margin belying expectations of a sizeable enough lead to counter No votes in more conservative rural or middle-class areas, along with neighbouring Dunbartonshire, Lanarkshire and Dundee. The capital Edinburgh, host to Scotland’s parliament at Holyrood, voted a surprising 60% in favour of the Union. Pro-independence partisans and several commentators were quick to opine that “Project Fear” had succeeded, referring to the No campaign’s strategy of scaring voters with possible negative impacts of Scottish Independence such as uncertainty about existing pensions and future jobs, flight of capital, withdrawal of the pound sterling, membership of the EU and NATO.

Whereas pro-Union Parties and supporters were guilty of complacence early on, the Yes campaign on its part probably underestimated the anxieties of substantial sections of the electorate and did not provide convincing answers to many questions that were troubling them. Even though Scotland’s first Minister Alex Salmond heroically led a vigorous and content-rich Yes campaign, his resignation from Scottish government and from leadership of the Scottish National Party (SNP) in the immediate aftermath of the referendum results, was probably an acknowledgement of some failures due to which support for Independence could not be pushed past the half-way mark.

Many voters seem to have opted for the known devil of a United Kingdom rather than the uncharted waters of an independent Scotland. Whatever role fear played in swaying voters towards the No option, panic in the Westminster establishment and all the UK-wide parties at the looming spectre of a break-away Scotland, certainly shook them out of complacency and triggered a belated but more positive campaign justifying it Better Together name. The eleventh hour promise by all three main UK-wide Parties to bring about greater devolution of powers, the so-called devo max, even after a No verdict, must also have swayed a substantial chunk of fence-sitters.

Yes campaign more than nationalism

Even though Scotland ultimately voted to stay in the Union, fact is that 2 out of 5 Scots voted to leave the UK. The results of the referendum leave the protagonists on both sides of the argument with many troubling questions, and many lessons to be learned. Not just Scotland, but Wales, Northern Ireland, England and the Union as a whole have much to ponder over. The Scotland referendum process has been keenly followed by other restive regions such as Catalunya in Spain, the Flemish part of Belgium, Russian-majority regions of Eastern Ukraine and, nearer to home, even in Kashmir on both sides of the LoC.

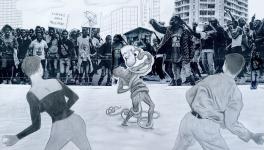

One of the noteworthy features of the campaign for Scottish independence was its appeal and reach far beyond nationalism and cultural exceptionalism. While there were undoubtedly some Yes proponents who flaunted kilts, tartan plaid, bagpipes and traditional Scottish highland sports, most of the campaign looked forward to a different future rather than backwards at Scottish history. The famous Scots clans led by lairds or landlords who, between about 500 families own over 75% of land in Scotland, were overwhelmingly with the Union, as were owners of the unique Scotch whisky distilleries. Younger voters, lower-rung workers, and deprived and disenfranchised sections, favoured Independence. Both sides of the issue agreed that the campaign was a truly energizing exercise in participative democracy that motivated almost all adult citizens (here defined as over 16) to discuss in depth many issues that touched their lives.

The Scottish National Party (SNP), mistakenly viewed by many outsiders as a mainly nationalist force, actually led the pro-Independence campaign on a much wider range of socio-economic and political issues such as free education (as against the high tuition fees levied by the Tory-Lib Dem government triggering widespread student protests), revival and strengthening of the National Health System (NHS), a deepening of the welfare state, a suitably reformed income tax regime, and a host of other measures seeking to promote egalitarianism in the face of the highly unequal society (among the most unequal in Europe) that the UK has now become. The Yes campaign also called for expulsion of the UK’s nuclear submarine-based deterrent from their only bases in Scotland. In many ways, it was the Better Together campaign that continually appealed to British nationalism and a sense of “Britishness” as raison d’être for retaining the 300 year-old Union.

Backing for Independence came from well beyond the SNP and its support base, itself embracing a far wider section of Scottish society than the fringe following it had two decades ago. A substantial section of Asians, mostly Sikhs and Scotland’s largest minority, supported Independence as a stepping stone towards a greater role in decision-making and more autonomy from an exclusivist Westminster elite. Large sections of the traditionally Labour-supporting classes, around 27% according to some post-referendum studies, switched to the Yes camp. The pro-independence vote clearly reflected a widespread rejection of the neo-liberal consensus at Westminster melding together the Conservatives, the Liberal Democrats as well as New Labour, with even the fast-rising and right-leaning UK Independence party not challenging it. The media too, almost universally bar the Herald from Glasgow, favoured the Unionist side and echoed the common conservative critique of by lampooning Yes supporters as those constantly wanting more subsidies, handouts and doles.

Posers for major political parties

Given the long-standing inclination of Scotland to elect Labour MPs, for instance having sent 40 Labour MPs to Westminster out of a total 60 in the previous elections in 2010, it was little wonder that the Better Together campaign comprising all three major UK-wide parties was chaired by Alistair Darling, former Chancellor of the Exchequer under Prime Minister Gordon Brown. Brown, who threw himself energetically into the campaign only in the last fortnight, is widely credited with having won over sizeable sections of traditional Labour voters to the No camp at the last minute, despite the distaste of Scottish Labour supporters at seeing Labour in bed with the Tories in this campaign. With the Tories having only 1 MP from Scotland (the Lib Dems have 11), and with PM David Cameron being widely disliked there, the No campaign pushed Labour to the forefront. From the steps of 10 Downing Street, David Cameron rightly congratulated Darling for the successful No campaign. But this credit for the Unionist victory is a double-edged sword and Labour will probably pay a heavy price for it in Scotland in the next general elections due in 2015. The fact that the Labour leader Ed Miliband was almost as ineffective, and almost as disconnected from the average voter, in the Scotland campaign as David Cameron was does not augur well for the new generation of New Labour leadership.

Having almost presided over the break-up of the United Kingdom, the Tories under PM David Cameron are in all sorts of trouble. Cameron’s first move has been to virtually renege on his promise of devo max or greater devolution of powers not only to the Scottish parliament but also to the Assemblies in Northern Ireland and Wales (the least empowered). Cunningly introducing a caveat he had not revealed during the referendum campaign, Cameron linked devo max to comparable devolution within the same time frame in England, which is today governed directly by the UK Parliament at Westminster, and evolving institutional mechanisms for “English votes for English laws.” (This is the so-called West Lothian question, the term deriving from the constituency of the Labour MP who first raised the issue in 1977 when the proposal for a devolved Assembly in Edinburgh was initially discussed.)

Implication is that devo max could take much longer than No voters in Scotland were led to expect, especially since England-centred devolution would probably involve re-writing the hitherto unwritten Constitution! Cameron may have felt he has upstaged the right-wing UK Independence Party while also wrong-footing Labour. But the Tories now risk provoking a backlash and even greater distrust in Scotland and elsewhere in the UK, perhaps hastening an earlier call for another referendum than may otherwise have happened. This cynical and dangerous Tory ploy of stoking English nationalism and majoritarianism, can only further alienate the other nationalities in the Union.

Major issues bedevil the Union

Regardless of the result, the Scotland referendum has thrown the cat among the pigeons with respect to the political structure of the United Kingdom and its constituent nationalities in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. There is already some considerable English backlash to Scottish devolution or possible independence, and parties like the Conservatives and UKIP are playing with fire by encouraging such sentiments and supposed grievances. Questions being raised, which some polls have suggested have the support of as much as 65% of the English population, include why should Scottish MPs be allowed to vote on English issues in Westminster when Scotland has its own Parliament, and why should Scottish Ministers hold certain portfolios in the UK government on subjects that are under the jurisdiction of the devolved government in Scotland? If answers to such questions lie in federalism, what would such a federal structure look like? Is there still room for a central Parliament in Westminster? And if there is an English Parliament covering 85% of the UK population, would it not wield de facto power over the rest of the Union?

Another major conundrum will be posed by the proposed “in-out” referendum to be held in 2017 on whether the UK should stay in the EU or exit it. Membership of the EU was an important plank of the pro-Independence campaign in Scotland. The Yes campaign countered the supposed benefits of staying in a larger Union, namely the UK, with the idea of Scotland becoming part of an even larger entity namely the European Union! The Scottish government in Edinburgh even brought out a White Paper on the subject! Doubts as to the viability of an independent Scotland were answered by the Yes campaign pointing to the success of similarly-sized Denmark and other EM member states. The piquant question now is if the UK as a whole, with only 15% of its population in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, votes to exit the EU, where does that leave regions like Scotland which want to stay in? Labour, and the Left in general in the UK, have many issues to think about.

Finally, the Scottish referendum has sent powerful ripples across Europe and even further afield. Spain continues to rule out any similar referendum in Catalunya where long-standing clamour for independence may lead to a “non-binding” vote on the issue later this year or the next. Spain also declared, well before the Scottish referendum was held, that Scotland should not expect automatic EU membership and that Spain would oppose its entry! Belgium said more or less the same, worried about implications for its restive Flemish-speaking region. Even the former EU Commission President Jose Manuel Baroso stepped into the Scotland fray, stating that the EU has no provision for admitting countries formed by breaking away from member States, clearly pandering to and echoing the anxieties of many EU countries.

After the Scotland referendum, many countries and groupings have cause for worry. Not only about self-determination but also about participatory democracy.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.