Remembering Another Rama on Ram Navami

Several groups associated with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) are holding the “largest ever demonstration in Bengal” over a week till April 11th to mark Ram Navami. The rallies will be “fully armed”, said RSS sources to The Hindu on the 5th of April. The news item continues: “In the districts,” the news item continues, “they will be carrying swords, tridents as well as bows and arrows.”

This ominous use of a martial Rama in a public rally brings another time, and another Rama, to mind.

After the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, several writers were invited to speak to school children about what had happened. Many teachers told us that their students were puzzled and disturbed by what they had heard on television, in their homes and their neighbourhood. In response, Shama Futehally and I got together with other writers to retell, for children, what we called “the jigsaw puzzle that is India”.

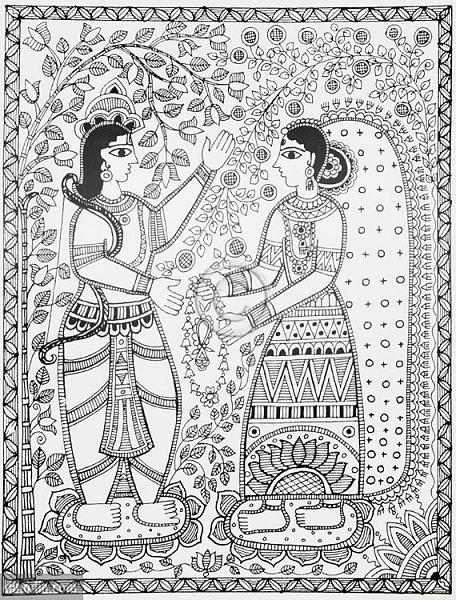

I decided to write a story about the many Ramas we know. The Hindutva brigade sees only some faces of Rama. They only talk about Rama as a god they have exclusive access to, or as a warrior bearing weapons, or as a stern husband or king laying down the rules. In effect, they miss out on the many dimensions, the richness, of the men and women who people our epics.

Remembering a story of Rama as, above all, a compassionate man, I decided that this was the face we needed to see once more, so we could insist that no one’s story is complete. Nor does it have a monopoly. Our cultural legacies have meaning for us only if we tell and re-tell multiple stories of heroic figures, whether mythical, legendary or historical.

Rishab’s Rama

Rishab pushed open the door of his house and ran in. His bag flew from his back on to a nail on the wall.

“First time!” he shouted gleefully. He had been practising for months, and now the bag had flown to its right place almost on its own, as if it had a pair of wings.

“Is that you, Rishab?” called his grandmother, coming in from the kitchen. Rishab grinned to himself. His grandmother asked this question every single day. The running footsteps and the bag’s slap against the wall told her who it was, but still their afternoons together always began with this question.

Later, after they had eaten and she had washed the dishes, they lay down side by side.

Sometimes, when Rishab thought about which part of the day he liked best, he found it difficult to make up his mind. He loved the early morning when he woke up to the sound of his grandmother singing under her breath, as she picked flowers in the muddy little patch behind the house. Or the evening, when his mother got home from work, then his father.

But the afternoons were, he decided, the most peaceful. His grandmother and he would lie side by side, the sun streaming in through the window into the quiet room. Or she would tell him stories, stories different from the kind he read, or heard in school.

Some days, she would sing him one of the hundreds and hundreds of songs she knew. She had a soft, trembling voice, but she knew what every word meant. Rishab could tell, from the way she sang, that she believed in the song. He could see how much she loved it.

Sometimes she would sing a story-song; a story from the Ramayana or the Mahabharata.

She told Rishab once, “Rama is called karuna-samudra. Do you know what that means?”

Rishab shook his head.

“Karuna is like pity,” she said. “The gentle, sorry feeling you have when you see something that needs your kindness. Samudra of course is a deep deep ocean. So you see, there is no end to Rama’s kindness, or his tenderness for all living things.”

Then one day, Rishab came home later than usual. His grandmother stood at the door, waiting for him.

He went in with her, so full of news that he forgot to make his bag fly on to the nail on the wall.

“Pati!” he said, breathless, before she could ask him why he was late. “I saw a big procession today on the way home.”

“Oh? What procession was that?” she asked him, taking the bag off his back.

“There was a huge cardboard Rama with a bow and arrow. There were people with loudspeakers on a lorry. And everyone was shouting ‘Jai Shriram! Help us to defeat our enemies!' ”

Rishab was so full of the crowds he had seen – the colour, the noise and the marching that had reminded him of an army – that he didn’t notice how silent his grandmother was.

“And then, when the procession had marched down the road, I ran after it till the market,” said Rishab. “Look, one of the men with a trishul in his hand gave me this kumkum.”

Grandmother didn’t even look at it. “Put it away and come to eat,” she said.

Rishab was so excited by what he had seen that he had forgotten how hungry he was.

Later, as they lay side by side, Grandmother suddenly said: “Rishab, when Rama, Sita and Lakshmana were in the forest, they saw a deer grazing near their hut. It had a beautiful tail.”

“Sita admired the tail very much. She thought she would like to take home a tail like that to remember her years in the forest.

“Rama decided to get the deer’s tail for Sita.

“But the deer suddenly turned around. Now Rama could no longer see the tail. Instead, he saw the deer’s large, trusting eyes, and its defenceless neck – stretched out as if it was offering it in place of its tail.

“Rama was filled with pity, with tenderness. Sita didn’t get the deer’s tail. But as they went back into their hut, their faces – the faces of Rama, Sita and Lakshmana – were full of wonder at what they had seen: the beauty of love and trust between two living creatures.”

Grandmother stroked Rishab’s hair gently. “I know that look,” she told him. “That face of Rama you don’t need cardboard to see.”

Rishab looked at her, a little puzzled by Grandmother’s earnest face.

“Do you remember what I called the song I sang yesterday?” she asked him.

“Yes,” said Rishab, “you called it prema bhakti.”

“Do you remember what that means?” she then asked.

“A prayer that is love,” he replied.

And Rishab remembered the song again. He saw a peaceful, loving, generous face, like Rama’s when he spared the deer. This was the face of Rama that he saw in his head whenever he heard Pati sing.

“But Pati,” he said, still puzzled, “this face looks different from the cardboard one. Are they two different Ramas?”

“Sleep now,” said Grandmother, her voice barely above a whisper. “Rama lives in your heart, not on cardboard or in some building. And a prayer – or a song of love – does not need loudspeakers.”

Then they fell asleep together, side by side, as if they had travelled a long distance that afternoon.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.