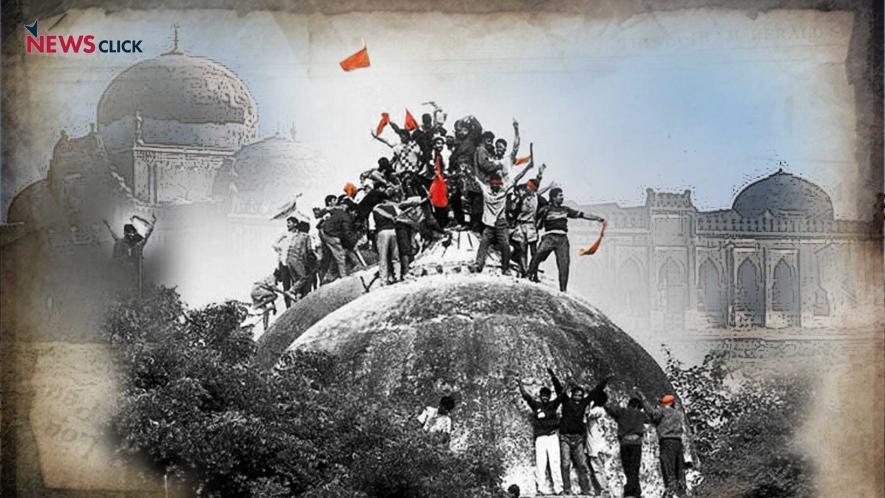

Babri Masjid Demolition was the First act of a Retributive Tragedy

Two books – the first written in 1993 and the second published almost three decades later in 2021, innumerable articles, several television and video shows and talks later, I still feel that one can never have enough of writing or talking about the demolition of the Babri Masjid and how the event 'reconfigured' India. There are countless ways to recall the events in either time sequence – the early years of the agitation till contemporary times, or begin with the current period and go back into the past.

Whenever weighing in the mind if one should write another and risk repeating oneself, the first realisation is the 'sense of duty.' As a person on the 'wrong' side of India's demographic tide, it is the obligation of my generation to share firsthand socio-political cataclysms and good fortunes.

Doubts are overcome by the fact that almost 52% of Indians are below 30, meaning they have no living memory of events three decades ago in 1992. Add another 7-8% of those who would have been less than six years old.

This is the age when most people begin storing memories in the 'active' drive in their brains. Effectively, this leaves nearly 60% of people with little or no memory of the events leading to the demolition. Just as the generation I belong to learnt about India's independence and the national movement that preceded it from our elders and, of course, textbooks, the ones below their mid-30s could do with a helping hand from us.

Sharing information and perspective becomes all the more essential because textbooks are fast changing, and so is official historiography. Unlike the past, the present has become a doorway to the past – our politics of the present moment decide what history we would like to believe in – were India's medieval ages assimilative or repressive, for instance?

The history of the Babri Masjid is almost five centuries old, given that the founder of the Mughal Empire, Babur, arrived in India in 1526 and two years later was purported to have issued the edict for the construction of the mosque that existed till December 6, 1992.

The history of contemporary Ayodhya is older – beginning with the sixth century BC when the first signs of human habitation were found during archaeological excavations conducted under the aegis of the Archaeological Survey of India.

History, especially when discussing any issue or event that is doubly contentious, has a tendency to get unnecessarily long-winded. Instead of examining the deep past, it is more prudent to limit to events immediately preceding the demolition, the violent action on that fateful day and the fallout – in the short-run as well as the long-term.

Although earmarked as the issue that had the potential to catapult the Sangh Parivar to the centre stage, the agitation for a Ram temple in place of the Babri Masjid began in real earnest only after stormy petrel of Muslim politics in the 1980s, the retired Indian Foreign Service officer, Syed Shahabuddin, called for boycotting Republic Day celebrations in 1987.

Although the protest was withdrawn, it provided an opportunity for Sangh Parivar leaders to accuse Muslims of placing religious matters above the nation's foundational day. Lal Krishna Advani said the threatened boycott was "antinational, inflammatory and irresponsible...(and a)... unabashed attempt to intimidate the nation by threats of violence." The VHP accused the Muslim leadership of putting "religion over the nation."

Effectively, when the Babri Masjid was demolished, the agitation had been waged for just five years. But in this short period of time, the nature of the dispute had widened – not only were the mosques in Varanasi and Mathura introduced to the wish list but an alternate view of history was being peddled.

After initially claiming that they would "prove" the existence of Ram and that a temple indeed existed at the site of the Babri Masjid, the stand was altered when it dawned on them that the antiquity of contemporary Ayodhya was not that old and also that there was no archaeological evidence of a Ram temple being demolished for raising a mosque.

That was when the infamous slogan was penned: Ram is a matter of faith. Since then, the argument has been used ad nauseam – be it regarding the alleged finding of a shivling in the Gyanvapi Mosque or that plastic surgery and in vitro fertilisation (IVF) were regular practices in ancient India.

The BJP was in power in Uttar Pradesh when the mosque at Ayodhya was torn down. The government at the Centre had a Congress leader at its helm. While Kalyan Singh indulged in doublespeak and promised to safeguard the structure, he did nothing to prevent rampaging mobs from assembling in the temple town. His behaviour was the polar opposite of Mulayam Singh Yadav, who in 1990 almost lived up to his pledge: parindey ko par nahi maarne doonga (even a bird would not be allowed to flutter its wings in Ayodhya).

PV Narasimha Rao deluded himself – outwardly stating that he took Sangh Parivar leaders' words at face value, but deep down possibly nurturing that the Babri Masjid's demolition would be 'good' for the nation because the BJP and its allies would lose the 'hate symbol' they had in their clasp. The Supreme Court, which could have stepped in, chose to delay decisions, possibly because judges felt that it was the responsibility of the political leadership or the Executive specifically, to ensure that law and order were maintained and no constitutionally mandated guidelines were violated.

As a result, no decision was reached in time on the land Kalyan Singh's BJP government had acquired in Ayodhya and handed over parts of it to the Vishwa Hindu Parishad. The criminal case for the demolition was filed in the immediate aftermath of what the Supreme Court, in its final November 2019 judgement, stated was an "egregious violation of the rule of law." The judgement was finally delivered by a CBI court in September 2020 – underscoring the deeply flawed nature of the judicial system in India. This case was illustrative of the partiality of the entire legal process involving the Babri Masjid from the time the idols were forcibly installed inside the mosque.

For the romanticist in me, it was a tragic irony that the Babri Masjid was demolished on the day that was also the 36th death anniversary of Dr BR Ambedkar. That he was popularly referred to as the Father of the Indian Constitution made the coincidence infinitely more paradoxical.

But for the cynical side of my persona, primarily shaped by the ringside view of the rise and growth of the Hindu rightwing political groups in India, there could not be anything more symbolic: expectations of the rule of law being enforced to protect basic rights guaranteed under the Constitution were also laid to rest on Ambedkar's death anniversary.

No year has passed when Prime Minister Narendra Modi has not "paid homage" to Babasaheb's "Mahaparinirvan Diwas" and recalled his "exemplary service to our nation. His struggles gave hope to millions, and his efforts to give India such an extensive Constitution, can never be forgotten."

Such statements typify utterances of this regime – term Parliament as the 'temple of democracy' but trample it like one wouldn't a temple desecrate, call it the 'only Holy book' but run the Constitution's spirit like one would recycle waste to make it unrecognisable.

For much of that day, journalists had no time to let emotions a free run. But late at night, after putting the newspaper to 'bed', as I had watched along with a few others, the dust of the Babri Masjid settle over its rubble, I realised how a decrepit mosque had become the symbol of the dream for India that our ancestors had clutched tightly while fighting colonialists.

India now possibly prepares for several more anniversaries on the lines of Babri Masjid's demolition. The Sangh Parivar has made considerable progress in seizing the Gyanvapi Masjid and the Shahi Idgah – the path becoming easier with a regime in place, a more pliant judiciary and, more importantly, with the altered thinking of a significant section of the population. The constitutionality of the Places of Worship Act is also under challenge, and the basis of the Ayodhya verdict may get knocked off completely.

The slide into a section of society being blasé about justifying violence and constantly holding hatred against anyone who disagrees has happened over the past thirty years. Probably a large number of Indians in post-colonial India never agreed with the path the country chose and the relations it forged between diverse religious communities.

All it required was a leader to come along and say that holding prejudice was not politically incorrect. It required someone to signal, by words and actions, that spreading fear and distrust was justified for unspecified "indignities in history."

When we look back at December 6, 1992, realisation dawns that it was not the violent endpoint of a political narrative. Rather, it was the first act of a much longer and more retributive tragedy that would continue to unravel bit by bit.

The writer is an NCR-based author and journalist. His latest book is The Demolition and the Verdict: Ayodhya and the Project to Reconfigure India. He has also written The RSS: Icons of the Indian Right and Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times. He tweets at @NilanjanUdwin

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.