The 1918 ‘Spanish’ Flu Pandemic in India and Eerie Similarities to COVID-19 in 2020

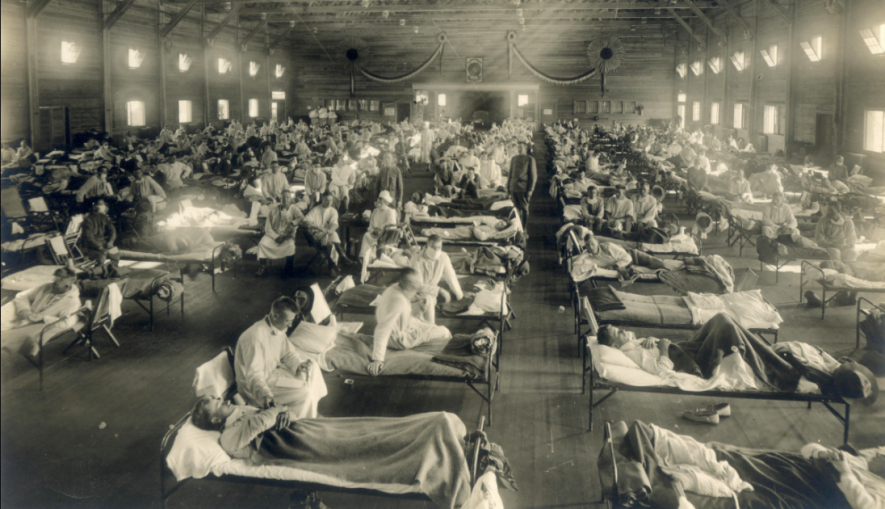

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, ill with Spanish flu at a hospital ward at Camp Funston

Last week, the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) of the Indian government asked its universities and research institutes to ‘delve into their archives’ to study how British India handled the 1918 H1N1 pandemic- commonly referred to as the ‘Spanish’ Flu. The suggestion was based on a legitimate belief that the research will help support the broader effort of the Government in its fight against the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Although it took a pandemic for the wider importance of historical research on science, technology and medicine (STM) to be acknowledged, this beginning, however limited, is welcome, and it sincerely hoped that the MHRD allocates more resources to Indian universities and research institutes in the future to encourage critical research on the historical aspects of STM in India.

The experience of the ‘Spanish’ Flu in British India does not, however, offer lessons that are radically different from some of the genuine demands that have emerged over recent days in the wake of the lockdown necessitated by the COVID-19 outbreak in India. These involve curbing hunger and malnutrition among the poor and vulnerable, providing adequate personal protective equipment (PPEs) to health workers and adopting a broad-based and inclusive approach in organising relief efforts. If anything, the evidence from the 1918 pandemic confirms what most of us already know; that a hungry, famine-stricken population with serious deficiencies and shortcomings in its medical infrastructure provides a fertile ground for a debilitating attack by a highly contagious and lethal virus.

The 1918 pandemic and its impact

Contrary to its name, the ‘Spanish’ flu that swept the globe in 1918 seems to have originated in the United States. Some of the earliest recorded cases of the virus were among army recruits in Kansas in the US, in March 1918. The virus seems to have then spread eastward across Europe, and then to the rest of the world from Northern France in April 1918, reaching India and China in June. Given that the pandemic swept the world during the First World War, troop movements, amply aided by transportation, via railways and steamships acted as an important conduit for its transmission.

The pandemic itself struck in two waves, broadly. The first was a mild wave that lasted until July, while the second, more virulent, wave began in late August and continued into 1919. The second wave of the disease was one of the most lethal pandemics to have swept the world, accounting for a global death tally running into tens of millions of people.

Complications to the respiratory tract and lungs were considered to be the key reason for a number of such deaths. British India (including modern day Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar) was the region that saw the most number of causalities due to the pandemic, with the estimated number of deaths between 12.5 and 20 million people (close to half of all deaths due to the pandemic). British India was followed by China which was witness to between four to nine and a half million deaths and Sub-Saharan Africa, which saw between 1.7 and two million deaths. In this sense, the 1918 influenza pandemic affected the poorer countries and regions more severely than the richer ones.

Even within countries, it was the poor and the deprived that bore the brunt of the disease, as examples from British India will amply indicate. In 1918, vast parts of India faced famine-like conditions following the failure of the south-west monsoon. Famine was officially declared in two Indian provinces- Central Provinces (includes parts of today’s Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh) and the United Provinces (today’s Uttar Pradesh)- while the lack of rains also seriously affected areas in Bombay presidency. These famine-stricken regions were also the most severely affected by the disease.

For instance, the Central Provinces registered the highest mortality per 1000 people due to the disease at 67.6, followed by the Bombay Presidency at 54.3 and the United Provinces at 47.2. The corresponding rates for Madras Presidency (15.8) and Lower Burma (16.2) were in the range of the global average rate of between 13.6 and 21.7 per 1000 people.

The economic strain due to war-time inflation and commodity shortages further exacerbated these difficulties by making essential commodities such as food and kerosene dearer, and thus beyond the reach of the vast majority of the population. Although not directly related to the disease, parts of Madras Presidency witnessed food riots in September 1918, indicating the extent of economic deprivation that was rife among the Indian population of that period. The mortality statistics of Bombay city in late 1918 provide more clinching evidence of the differential impact of the disease on the country’s poor and deprived sections. The category ‘low-caste Hindus’ – which refers to the socially oppressed sections in India – registered the highest case specific mortality rate per 1000 people in the city at 61.6; a number much higher than the average rate for the remaining categories of people, which stood at 14.35. The numbers certainly indicate who the most likely victims of an epidemic disease will be. Therefore, any relief effort during such epidemics should be specially geared towards increasing access of food and essential commodities to these sections if a catastrophe of the magnitude of the 1918 flu is to be avoided.

Although there did not seem to be any economically disruptive ‘lockdowns’ in 1918 like the ones we are currently witness to in 2020, the period had its fair share of serious economic dislocations, as workers and professionals were incapacitated by the disease. Unlike COVID-19, which is known to attack relatively older people more severely, the ‘Spanish’ flu in India severely affected people in the working age group who were between 20 and 40 years of age. From mines to textile manufacturing units and agricultural fields to the docks, workers belonging to most sectors of the Indian economy were directly affected by the disease. In Bombay presidency, the aforementioned monsoon failure and the reduction in workforce that this illness lead to meant a 19% reduction in the area under food crop cultivation, thus contributing further to food shortage in the country. The pandemic left deep scars on an already battered war-time Indian economy.

Responses to the pandemic

The colonial government’s response was directed along two lines – relief and research. However, on both these counts, its efforts proved inadequate to handle the severe onslaught of the virus. In 1918, India possessed a fragile medical system urgently in need of expansion, concentrated as it was, chiefly, in its cities. War-time deployment meant that even this system was further depleted of its personnel. Private medical practitioners were available but they were known to charge exorbitant fees, using the pandemic as an opportunity to make money, thereby making medical care even more expensive to the general populace. A large section of medical practitioners were themselves struck down by the disease, and were incapacitated at a time when they were needed the most, highlighting the importance of providing adequate protection to the health workers at the forefront of treating contagious diseases.

In Bombay city, as the incidence of the disease began to peak, hospitals were overflowing with patients and crude versions of dispensaries were raised on the roadsides to provide medical relief in an effort that roughly parallels the construction of makeshift hospitals in many parts of the world following the recent outbreak. The colonial government met the virus outbreak with a sense of resignation and helplessness, and found isolating a large number of patients affected by the virus ‘impracticable’. Facing a paucity of health workers, the Bombay city’s municipal corporation gave a call for volunteers to help, even with its medical relief efforts. It also opened up cheap grain shops, and attempted to provide foodstuff such as milk for free to the patients.

The government’s scientific research work was geared towards developing a vaccine to treat the disease. This effort did not create a big impact, given the then prevalent lack of clarity in the medical knowledge of that period on disease causation. There was a lack of consensus on what the specific germ that was responsible for this outbreak was. It was then widely believed, albeit with doubts, that the disease was caused by a bacteria, bacillus influenzae, and it was not until 1933 that the virus that caused this pandemic was isolated.

Fortunately for India, the pandemic rapidly lost its virulence from December 1918, although, not after claiming millions of lives. One contemporary estimate of the morbidity of the disease put the figure at between 50% and 80% of the population of India. As the epidemic receded in Bombay city, its health officer showered his thanks on the city’s private individuals and non-official organizations for their voluntary services in carrying out relief work in the city. This effort during the 1918 pandemic was an early precedent to the impressive relief efforts undertaken by a huge number of volunteers in different places in India following the recent COVID-19 lockdown.

It has been more than 100 years since the devastating Spanish influenza outbreak happened in India. While there are important differences between it and the pandemic we face now, some of its lessons certainly continue to ring true for contemporary India, as well as for other developing countries, that in the short term, the virus cannot be effectively fought without fighting hunger and deprivation, if large scale human suffering and devastation is to be avoided. While at the same time, this examination of the past also emphasises the importance of providing adequate protection to health workers. This examination also shows that a broad- based and inclusive co-operation of the state with non-governmental outfits such as civil society groups, trade unions, peasant organizations and the like can certainly be used as important vehicles to direct and deliver short term relief. In the longer term however, prioritising liberal expenditure on the country’s public health infrastructure to vastly increase its capacity to effectively respond to epidemics, would be a useful starting point. In this regard, it seems that even supposedly richer countries seem to have forgotten this very important but basic lesson from the ‘Spanish’ flu.

The author is a PhD scholar at the Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine at King’s College in London. He is on Twitter @ViswanathanVe11

The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.