In Jharkhand’s Asbestos Clean-up, Victim Compensation Remains Elusive

Scarred dump visible from distance.Picture Credit to iBAN (India Ban Asbestos Network).

The inhabitants of 14 villages near Roro hills in Jharkhand live in the vicinity of asbestos mines that were abandoned decades ago. Since these mines were not scientifically closed before being abandoned, there still exist tonnes of asbestos tailings, scattered in and around the mines, which have a hazardous effect on the health of the tribal communities that live here. These waste particles have also contaminated the land, nearby streams, and the Roro river.

The mines in Roro were leased to Hyderabad Asbestos Cement Product Ltd (now known as Hyderabad Industries Limited or HIL) in 1963 to mine chrysotile asbestos. HIL was also involved in milling raw asbestos on-site to produce chrysotile asbestos fibre. The mines employing 1,500 workers were one of the largest asbestos mines in India. In 1983, the company stopped its mining activities as it ceased to make profits. Blatantly, the mines were abandoned without adopting safety measures for restitution of the mines, which is necessary to mitigate the adverse environmental and health impact in the mined area and its surroundings.

It is medically established that when asbestos fibres are released into the air, they can be easily inhaled, and may remain in the lungs for long periods. This can cause lung cancer, mesothelioma, and asbestosis, among many other asbestos-related diseases (ARDs).

erosioned roro hills. Picture Credit to iBAN (India Ban Asbestos Network).

When the adverse impact of asbestos waste exposure first became evident in these villages, Environics Trust, a Delhi-based community development organisation, along with the local organisations and independent researchers, did an intense study on the mines, collated information from the affected community, and identified similar unregulated mining practices across the country.

Based on their findings, in 2012, a landmark case was filed by the NGO in the National Green Tribunal (NGT), on behalf of the victims, seeking directions for scientific restitution of abandoned asbestos mines, and for creation of a trust fund for rehabilitation of the victims. It is also pertinent to mention that while the mines were in operation, the mine workers were unaware of the health risks they faced, and also oblivious of the Indian legislation on occupational diseases.

Even though asbestosis is a notified disease in Schedule III of the Factories Act, 1948, HIL did not conduct regular health check-ups, follow safety measures, and create awareness about the dangers of asbestos dust. Also, in violation of section 25(1) of the Mines Act, 1952, the disease was not notified to the government authorities.

Underscoring these violations of laws by HIL, the complaint filed in NGT sought appropriate compensation for the mine workers, and called for direct prosecution under section 27 of the NGT Act, 2010, for allowing asbestos dust pollution from the HIL mines while they were operational.

After several years of litigation, the NGT issued an order in January asking the state government to implement a restoration and compensation plan to protect the villagers from further asbestos waste exposure. In August, the state government submitted a compliance report, elucidating the schemes that have been initiated for conducting community health surveillance, and restoration of the mine area. A detailed project report was prepared for the rehabilitation of the mines with a financial outlay of Rs.13.45 crore.

The final order of NGT, and the subsequent compliance by Jharkhand state is a giant step in occupational health in India, which is otherwise an extremely neglected area of health.

Krishnendu Mukherjee, a barrister in London who represented the victims in the case, says, “The NGT judgement is a very significant decision because it confirms the important principle that companies will always be held strictly liable for their hazardous activities, however distant in the past and even if they complied with all the requisite laws at the time. The polluter pays principle which the NGT upheld in this case is an important mechanism for deterring companies from polluting through their toxic activities. It is hoped that the principle will be used for other sites of toxic exposure in India and elsewhere.”

The NGT judgement, however, skirted the issue of monetary compensation for victims, citing the absence of specific data or claims pertaining to the mines. The bench directed the state government to provide a forum to enable victims to make claims, and to confer power for adjudicating such claims on a sitting or retired officer/judge.

Environics Trust has taken up the matter of monetary compensation with the state administration. Dr. Sreedhar Ramamurthi, an earth scientist and managing trustee of the NGO, explains, “We are trying to convince the state administration to consider NHRC’s Special Report on Silicosis, submitted to Parliament in 2011, which gave an estimate of Rs.13 lakh as the loss to the worker in case of silicosis. We are arguing that Rs.5 lakh is already being paid by the government of Rajasthan to pneumoconiosis victims, and an inflation-adjusted amount should be given now to the victims of Jharkhand. Even in Jharkhand, Rs.4 lakh has been paid to silicosis victims four years ago.”

Health surveillance and mine-area reclamation schemes:

A committee set up by the state has taken a slew of decisions for rehabilitation and reclamation of the abandoned mines in Roro, which include laying of coir matting over the dump site; soil capping work; plantations and seed sowing around the dump area; installing display boards notifying people about the hazards of asbestos; building a retaining wall along the foothill of the dump; and bio-remediation.

The state government has allocated Rs.1.65 crore from the District Mineral Foundation Trust (DMFT) fund for various schemes involving construction of water tanks, repairing and construction of roads, and barbed wire fencing of the mine site. For these schemes, HIL will be asked to indemnify the state government.

Use of asbestos dump for road construction in the village. Picture Credit to iBAN (India Ban Asbestos Network).

Several schemes have been initiated to conduct community health surveillance. A health screening of 565 local residents revealed that 60 among them suffered from asbestosis. It is possible that the number of ARD patients is higher, since most ARDs have a long latency period spanning 20 to 35 years, and with their slow progression these diseases are often not identified as ARDs.

Weak implementation of occupational health laws in India:

There is no safe level of asbestos exposure, and therefore almost 70 countries worldwide have banned its use in any form. Despite the ban on mining of asbestos in 1993, India continues to import, use and process asbestos in significant quantities.

The most critical roadblock in seeking a ban on asbestos is the lack of acceptance and acknowledgement of the existence of ARD victims both by the government, and the employers. Moreover, the country’s health and safety legislation does not cover 93% of workers in the unorganised sector, where asbestos exposures are extremely high.

There is an urgent need to identify asbestos victims, and to provide them with necessary scaffolding to seek compensation from mine and factory owners. The India Ban Asbestos Network (IBAN), a public interest initiative, has launched several interventions to support asbestos victims.

Pooja Gupta, national coordinator of IBAN explains, “We have identified more than 1,500 cases of ARDs during several medical camps. Providing these victims a common platform to share their struggles and stories, and to motivate and support them is our main goal. We have also been legally engaged in seeking justice on occupational and environmental health in various courts. Our network members are constantly engaged in educating different stakeholders and awareness generation on such grave issues.”

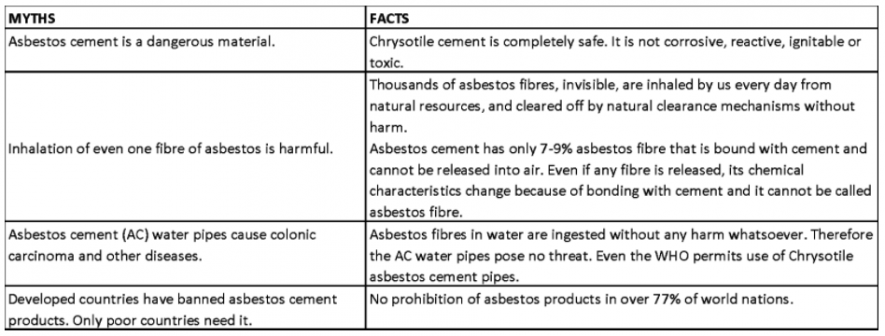

The WHO and ILO have repeatedly highlighted the carcinogenicity of all forms of asbestos. Yet, the Indian asbestos lobby maintains that chrysotile asbestos is safe for roofing and piping. The main lobby group - Fibre Cement Products Manufacturers Association (formerly known as The Asbestos Cement Products Manufacturers Association)—dismisses health concerns related to asbestos as “myths”.

Take for instance the “Myths and Facts of Chrysotile Asbestos Cement Products” listed on the website of the Fibre Cement Products Manufacturers Association:

According to official records, there are 112 large “asbestos-containing material” manufacturing plants present in India. A study suggested that there could be several more plants—either established prior to the Environment Protection Act coming into force or operating without clearances, and hence without any safeguards and permissions. Around 62% of these industries have not submitted any environmental compliance report, which is a mandatory requirement every six months. Moreover, only 38% of them have ever been inspected by the ministry.

Inspection of factories has hit a roadblock with the government’s attempt to improve ease of doing business. Ramamurthi says, “Currently there is a lack of proper inspection or compliance in factories, and this is a critical concern. Factory inspectors claim that inspection has become even more relaxed with the introduction of ease of doing business, and they are usually not allowed to inspect the factory on various grounds.”

Necessary government intervention:

The irresponsible use of asbestos is likely to lead to a spurt in the number of ARD patients in the coming decades. A study reveals that there will be at least 12.5 million [1.25 crore] ARD patients and 1.25 million [12.5 lakh] asbestos-related cancer patients worldwide in the near future, and half of them will be in India. The only relief that the government can offer to victims and their families is monetary compensation, investment in specialised healthcare, palliative care, and adequate diagnosis facilities.

The policy efforts by the government to improve occupational health in India has been encouraging in the past few years. The National Mineral Policy, 2019, has made the scientific closure of mines a requirement. The governments of Haryana and Rajasthan have launched a silicosis (2017) and pneumoconiosis policy (2019) respectively. Now, the Jharkhandis’ Organisation for Human Rights (JOHAR) has proposed to draft a pneumoconiosis policy similar to that of Rajasthan. Such efforts can help India achieve three of United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals that are directly related to health and safety at the workplace.

Through this case, the NGT has set a precedent by ensuring that the state government adequately compensates the community, and that the mining company indemnifies the state for this. For the asbestos victims of Roro, the state government’s compliance to the NGT order is only a partial victory. The litigation process for claiming monetary compensation will hopefully be a short one for them.

The author holds an MPhil in Economics from JNU and works as an independent researcher. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.