Note to ‘Anti-Nationals’: Strengthen Bonds Among Those Being Made Victims

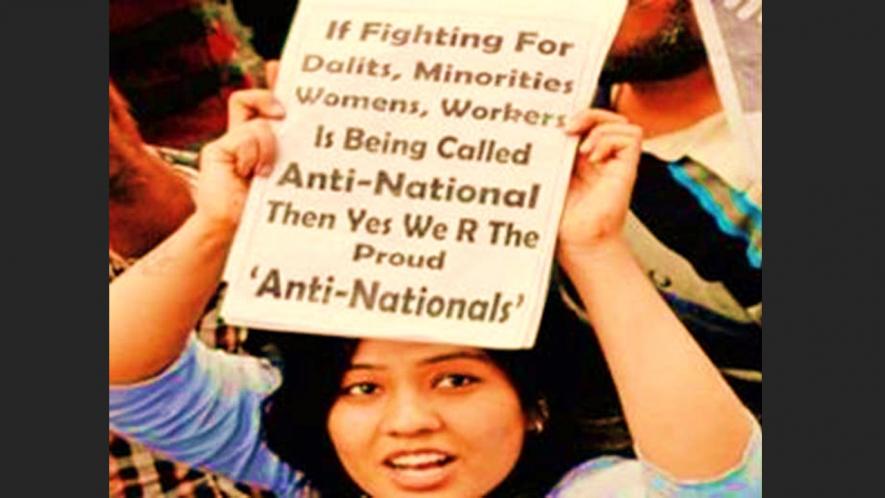

Representational image. | Image Courtesy: countercurrents

In its over five years in power, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has successfully created an ‘anti-nation’, a veritable nation populated by dissenters and victims of its ham-handed ideas of governance. This anti-nation can forge a new path, by neither reflexively reacting to the dominant ideas of power nor succumbing to its whims and fancies.

The process of creating the anti-nation started when the BJP started discrediting notions of social or political consent. Mob lynching marked the beginning of this negation of consent. Its recent moves in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) demolished consent at the level of the federal structure of the country.

While the government has projected the landmass of J&K as a part of the Indian nation since time immemorial, its inhabitants have been cast as ‘anti-nationalists’.

This abrogation of consent also marks the revision of syllabi in Delhi University. In the university, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), an offshoot of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or RSS, the ideological parent of the BJP, has demanded parts of various courses, particularly the history syllabus, be revoked. These moves are eerily connected to the communalisation of the National Register of Citizens or NRC in Assam. In all of its steps the government has sought to deploy nationalism to silence its critics.

It would be naïve to believe that the BJP and its various arms are solely driven by a desire to close the space for contestation. In Delhi University they have sought to claim their hegemony over the entire discipline of history by demanding that parts of the syllabus be subtracted. To wield the power to dictate terms, the RSS created a dogma of ‘urban naxals’ and ‘anti-nationals’. Its supporters coined derogatory terms such as ‘libtard’ and ‘sickular’ in order to strategically control and silence the mass media. It also privileged slogans such as ‘Jai Shri Ram’ and ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ over all other slogans.

Only after it put exclusion and polarisation into practice could the regime appropriate the NRC for communal polarisation or abrogate J&K’s autonomy to propagate essentialising myths throughout the country.

In this way, the present regime’s desire is to build an ‘anti-nation’, populated by so-called anti-nationalists. Their objective is to render citizens outsiders from within, to make certain groups and individuals espousing ideas different from theirs homeless within their homeland.

The anti-nation has made entire groups appear to be members of an imagined community that is always hatching conspiracies and fostering sedition.

All those who do not share its views are seen as inhabitants of this imaginary ‘anti-nation’ created by the regime. For this reason, the government is obsessed with weeding out ‘non-citizens’ and dissenters. What seems like an administrative task—such as carving two Union Territories out of J&K or identifying ‘illegal’ residents via the NRC—is actually an ideological project.

This anti-nation has been created by the BJP-RSS because it wants to establish a Hindu Rashtra. For this, everything has to be reduced to binaries—citizens versus non-citizens, Hindus versus non-Hindus, nationalists versus anti-nationalists. Without such binaries, the dispossession, deprivation and subjugation of large sections of society will become impossible to shove under the carpet.

In a way, the RSS has radically altered its fundamental objective. Today, it is far more concentrated on controlling counter narratives in order to perpetuate its own narrative. This is a strange form of exercising power, where the regime constantly generates imagined enemies and a sense of urgency to combat them. The so-called defiant individuals who make up this anti-nation have been foisted with the burden of proving their fealty.

Niccolo Machiavelli, the 15th Century Italian diplomat and historian, had said, “Everyone will be in my party without knowing it.” This Machiavellian logic dictates the terms of being Indian today. This twisted logic requires the press to be neutralised by the press itself. Journalism’s power is sought to be transformed into ‘journalism incarnate’. Like the Hindu god Vishnu, the press is re-imagined as a hundred-armed figure. Each arm stretches out to shape every variety of opinion into something that confirms to the regime’s worldview.

As Machiavelli had noted, the subjects in such a regime may think that they are speaking in their own language when in fact they are speaking the language of those in power. Those who think they are marching under their own banner, will be marching under the dominant order’s banner. Machiavelli would exult in the context of today’s India. Maurice Joly, the French satirist, says in his Dialogues in Hell between Machiavelli and Montesquieu: “I direct opinion at will on all questions of external and internal policy. I awaken people’s minds or lull them to sleep. I reassure them or confuse them. I plead for and against, the true and the false.”

It is in this context that the replacement of history by a compendium of myths should be seen. It is happening in step with propaganda subsuming news. History and news aid the creation of identity and knowledge, but even a remote possibility that either of them may unsettle the regime are being characterised as thought processes emanating from the imaginary anti-nation.

The 19th Century French political theorist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon had said, “The nation, in effect, gets likened to a herd of sheep where ‘glory, the most foolish of divinities and the most murderous, [takes] the place of liberty’.” Proudhon’s words would ring true for many a dissenting or disagreeing Indian today. The nation is constantly being projected as under threat while the dominance of those in power is rising in proportion.

Such a regime makes conventional ways of reclaiming history from the clutches of its abusers virtually impossible. This is why the Nehruvian notions of unity in diversity and harmonious coexistence have been falling upon deaf years. To speak of heterogenous histories will be seen as an expression from the ‘anti-nation’.

To many, Indian history is replete with conflict—continuous or intermittent—between classes, castes, and communities. For them it is necessary that they choose sides in such historical struggles. But the RSS wants to perpetuate these conflicts, not undermine them.

What those who are branded as members of the anti-nation can do is recognise that they can blunt and undermine the vengefulness and violence of the privileged. They can recognise that their ideas perpetuate not historical privilege but an alternate vision of the nation. This vision departs from the norms of the existing one in that it can bond people to one another by their being made into victims and martyrs.

Such members of an anti-nation would have a strength of their own. The anti-nation’s resilience would not arise out of opposing the RSS’ worldview. It would turn the RSS project to create an anti-nation on its head. It would denounce the premise of the RSS that a better future cannot be imagined with the baggage of a worse past. It can claim that whether the Hindu god Rama was born at the site of the destroyed Babri Masjid is irrelevant: What matters is whether those who destroyed it are brought to justice or not.

History-writing in India is often pulled in two opposing directions. The long-standing attempt has been to portray the past as harmonious, full of synthesis and relative amity. The response to this has characterised Indian history as one of discord, divergence, and overwhelming violence. ‘Myth-busting’ by the academia on both sides has often resulted in claims and counter-claims backing convenient truths. Their arguments have failed to influence the notion of history in the psyche of the common citizen. The argument that histories of conflict can and should be written without perpetuating conflict has not overstepped the bounds of the academia.

Thus, it is not sufficient to simply counter the abuse of history. What is required is a total dismantling of history’s hallowed position of power in the public sphere. Should this happen, those who abuse history to use it as a weapon, will not be able to mobilise it any further. This requires, however, that the abuse of history in order to create a nation is properly recognised and understood.

In his essay, On Nationalism, Rabindranath Tagore defined a nation “in the sense of the political and economic union of a people”, as “that aspect which a whole population assumes when organised for a mechanical purpose.” Conversely, the anti-nation category could include all those who are being excluded by the project of nation-building. Its fundamental characteristics can be non-conformity and heterogeneity. The subversive aim of the anti-nation would be to question and unsettle any national pride that subjugates citizens. As Tagore said, “…pride in every form breeds blindness at the end….”

In his Notes on Nationalism, George Orwell said, “Every nationalist is haunted by the belief that the past can be altered. He spends part of his time in a fantasy world in which things happen as they should — in which, for example, the Spanish Armada was a success or the Russian Revolution was crushed in 1918 — and he will transfer fragments of this world to the history books whenever possible.”

The British historian Eric Hobsbawm begins his 1992 paper published in Anthropology Today, Ethnicity and Nationalism in Europe Today, with the claim that “…historians are to nationalism what poppy growers in Pakistan are to Heroin addicts: we supply the essential raw material to the market… What makes a nation is the past, what justifies one nation against others is the past, and historians are the people who produce it.”

Yet, fighting the abuse of history does not require the reiteration of a firm commitment to a rigorous reading of the nation’s “real” history. What is indeed essential is to dislodge nationalism from the pedestal of being a high virtue and imagine an alternative idea of the ‘nation’ as we know it. Therefore, it is crucial to seize control of the making of the anti-nation, by suggesting that this idea transcends parochialism.

Even if India is not truly a socialist secular republic and never was, there is no reason why it should not be made into one. Connected in being relentless and unapologetic dreamers, the inhabitants of the anti-nation can lead the way.

Suchintan Das is a student at St Stephens College, Delhi University. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.