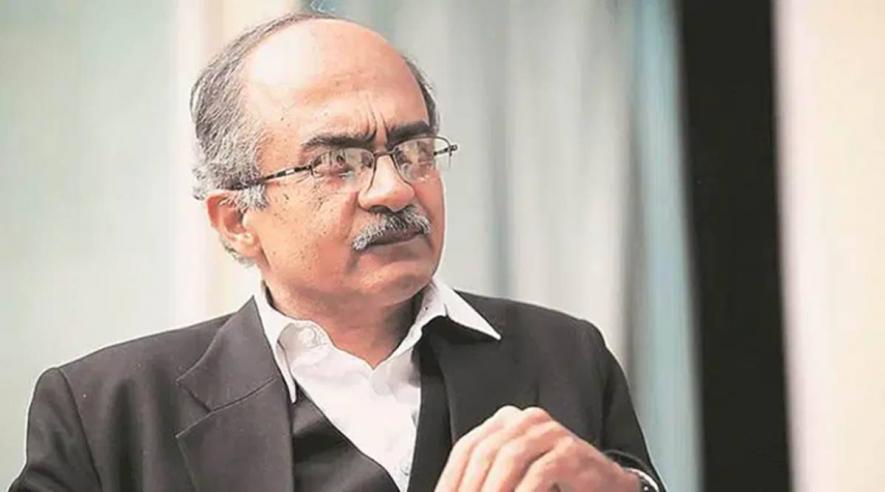

Will an Apology Make Prashant Bhushan a Mahatma?

Image Courtesy: The Indian Express

First, a confession: I often read court reportage, especially the obiter dicta and exchanges during hearings at the apex court. When I am tired, I have found these light-hearted exchanges between the bar and the bench hilarious. Notwithstanding the storied reputation of the highest court, these exchanges also show that august judges are human too. From time to time, reading a judgment of the highest court can also help glean the state of our judicial health and wellness. The honourable court itself has said that the judiciary is a “central pillar”. (This is rather in keeping with an Odiya proverb that elevates dhobi ghats—where we cleanse our linen—to the best indicator of a village’s health and hygiene.)

But nothing stirred my soul more than the sage words of Supreme Court Justice Arun Mishra in the Prashant Bhushan case on August 25. The court did, to be fair, sound rather desperate, clutching at the proverbial straw. The judge said, while reserving judgement in the case: “Tell me what is wrong in using the word ‘apology’? What is wrong in seeking apology? Will that be reflection of the guilty? Apology is a magical word, which can heal many things. I am talking generally and not about Prashant. You will go to the category of Mahatma Gandhi, if you apologise. Gandhiji used to do that. If you have hurt anybody, you must apply balm. One should not feel belittled by that.”

Going by media reports, the bench sought an apology after Rajeev Dhavan, Bhushan’s counsel, was critical of the court’s contempt judgment and labelled an order which says it will “only accept unconditional apology” as an “exercise of coercion”. Dhavan, according to LiveLaw, told the court, “An apology cannot be made to escape the clutches of law. An apology has to be sincere.” He said he has written over 900 articles on the apex court and that he once “said that the Supreme Court has ‘middle class’ temperament’. Is that contempt?” He reminded Justice Mishra that as Chief Justice of Calcutta High Court he had not initiated contempt against Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee for her comments that judges are corrupt. “Your Lordships took into account her position as Chief Minister,” Dhavan said.

I personally would deem the solicitation of an apology among the most masterly utterances I ever heard, a cerebration of the apex court as the upstanding protector of citizens’ inalienable fundamental rights. I read and re-read the words “You will go to the category of Mahatma Gandhi if you apologise.”

Really!

Such despairing words, but they were uttered with solemnity by the court. We have heard charges of bench-hunting and we have read how Bhushan is “not worthy of even contempt” (as Justice Dipak Misra opined in November 2017). The court once bristled against Bhushan and Dushyant Dave in the Judge Loya judgment delivered by Justice DY Chandrachud when it said in April 2018, “The conduct of the petitioners and the intervenors scandalises the process of the court and prima facie constitutes criminal contempt.”

However, the court took a “dispassionate view” and decided not to initiate criminal contempt proceedings, “...if only not to give an impression that the litigants and the lawyers appearing for them have been subjected to an unequal battle with the authority of law… The credibility of the judicial process is based on its moral authority. It is with that firm belief that we have not invoked the jurisdiction in contempt.”

I can only recall the words of Bhushan’s father, Shanti Bhushan, in an affidavit in 2010 in the same corruption case of past Chief Justices which is now being resurrected after a decade of somnolence: “...since the applicant is publicly stating that out of the last sixteen Chief Justices of India, eight of them were definitely corrupt, the applicant also needs to be added as a respondent to this contempt petition so that he is also suitably punished for this contempt. The applicant would consider it a great honour to spend time in jail for making an effort to get for the people of India an honest and clean judiciary.”

So the recent judicial past is really no guide into contempt jurisdiction. The law of the land is patchy, if not surreal. To cite another example, the notice for appearance issued to former judge of the apex court Justice Markandey Katju by a bench headed by Justice Ranjan Gogoi was seen to have diminished the dignity of the court itself.

Let us face it. The contempt of court law is a medieval monarchical appendage when judges exercised delegated kingly power. Any offence to the court was deemed to have offended an almost divine power! So antediluvian it looked, that even the hide-bound Britishers would let it slide.

It hardly needs repeating that democracy derives its arc from the Public Master, and Public Servants are supposed to be democracy’s mere servants. The master doubtless has the right to express itself within the bounds of constitutional law and rule of law.

“Justice is not a cloistered virtue.” We often mouth these words of Lord Atkin’s as legal cliché. “She must be allowed to suffer the scrutiny and respectful even though outspoken comments of ordinary men,” Atkin drove his point home. The judiciary must, like democratic India’s other public service organs, suffer criticism and open debate. No institution is absolute. The separation of powers and checks and balances within the system are part of a conscious design to stop the exercise of untrammelled power.

Ringing in my ears like tinnitus are the former French president Charles de Gaulle’s memorable words in response to the clamour to arrest author-philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre for civil disobedience during the Paris strike of 1968: “You don’t arrest Voltaire!” This is what defines a mature democracy—the desire to ensure that citizens’ freedom of expression is not stymied. It’s a pity that we are resurrecting the contrary, shushing the voices of dissent that are the heart of democracy.

Confident nations need no such forcing. An apology, like respect, is not enforceable. When demanded, the abstract notion of an apology willingly tendered shrinks, shrivels and evaporates. It morphs into coercion against the citizen’s moral compass. The bench would have done well to take into account Bhushan’s statement that an apology would amount to “contempt of my conscience”. We must all live and act as our conscience dictates.

The problem is in our feudal makeup. Public offices often (wrongly) vest public servants with an outsize sense of importance. Those who hold public office confuse themselves with the institutions they serve. That was the issue with the egregious framing of a sexual harassment charge against a chief justice as an attack on the judiciary. So appears to be the case here. There is a sore need for introspection among judges about their role in public service. Within the bounds of propriety, they, too, need an honest dialogue with their conscience and humility, to accept the democratic ordering of reality.

Seeking an apology is no prescription. For a common citizen caught up in these fraught times of a dystopic pandemic, here are a few morals for public officials everywhere to intone:

1. Never bite off more than you can chew.

2. Beware your intrinsic limitations.

3. Official perches are no vaccination against public put downs, more so in the age of social media.

4. No shield can protect the fragmented inner self. The tics and tells creep up in the unlikeliest ways and reveal whatever is going on in the inner recesses of the mind.

5. The same sauce works for the gander and the goose alike.

Lord Salmon, in AG vs British Broadcasting Council, 1981, described the term “contempt of court” as misleading. “Its object is not to protect the dignity of the court, but to protect the administration of justice.”

This is a final acid test that can help us reassess ourselves, including those who hold public office. The demand for apology will not wash.

The author is a former civil servant. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.