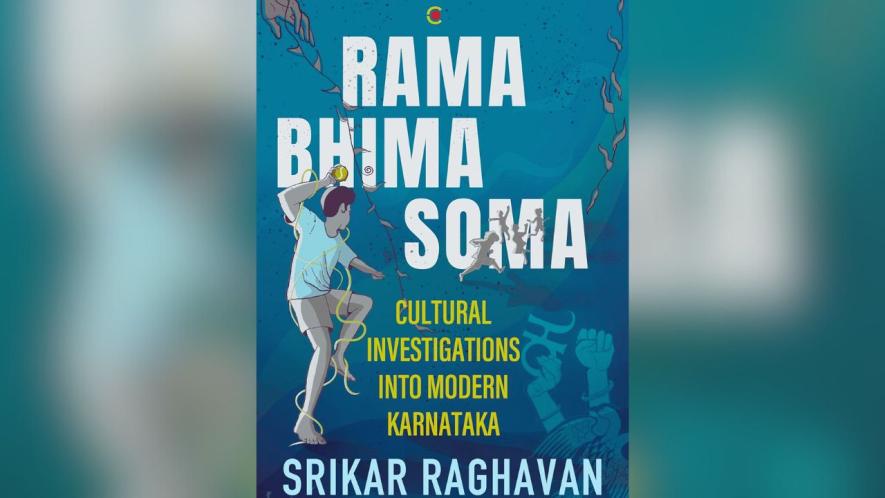

Rama Bhima Soma – A Bouquet of Stories and Conversations on Modern Karnataka

Karnataka is one of India’s most diverse states, as rich in literary and cultural traditions as it is in democratic struggles and political churns. The 20th century witnessed the birth of a modern Kannada renaissance, accompanied by the emergence of a powerful social conscience. One young man’s desire to explore this vibrant historical backyard, born out of a feeling of being linguistically unmoored, compounded by worries over an increasingly opaque political direction, leads to an ambitious—no, audacious—attempt to unpack the region’s social and cultural histories.

Rama Bhima Soma is an enterprise of translation and rediscovery, packed with stories and conversations. The life and times of legends like Kuvempu and Shivaram Karanth; the fall of socialism and the rise of the Hindu Right; the intellectual ruminations of U.R. Ananthamurthy, D.R. Nagaraj and M.M. Kalburgi; the wildly popular television serials of T.N. Seetharam and the community-centred one-woman theatre shows of Du Saraswathi; a brief history of Naxalism in Karnataka and glimpses of other complicated legacies of the 1970s’ Left—the book explores a dizzyingly wide sweep of Karnataka’s contemporary history, seeking, above all, to forge new connections and begin fresh conversations.

Marshalling a diverse range of literary and scholarly resources, framed through biographical sketches and immersive reportage, Srikar Raghavan’s genre-bending work of narrative non-fiction reanimates some pivotal moments in the making of modern Karnataka. The result is a sizzling dish of ideas rescued from the deep freeze of historical amnesia.

FIVE

Lost in Translation

Kannada after Boosa

When the raingod’s diamond

axed me at dawn,

glancing off a broken bottle

in the slum window

with half a broken wall,

it unbound the waters

throttled in my year of fever,

released a dynasty in my throat.

—A.K. Ramanujan, Soma: Sunstroke I 18 November 1973.

Seventeen days after the state of Mysore was renamed Karnataka.

Under the aegis of an Ambedkarite organisation, the Hosa Alegalu (New Waves) conference is underway in the centenary hall of Maharaja’s College, Mysore. A lawyer by the name of Sanjeevayya begins a speech in English, upon which some in the audience shout their desire that he speak in Kannada instead. Sanjeevayya continues to speak in English, undaunted. The blistering dalit politician B. Basavalingappa (popularly called BB) is also on the stage; he defends Sanjeevayya’s choice and makes a long statement expressing his personal thoughts on the subject. The following report appears in the Kannada newspaper Prajavani a few days later.

Reading Kannada books will not boost your intellect or patriotism

Minister Shri Basavalingappa is of the firm opinion that reading Kannada books will not improve anyone’s critical thinking, courage or service-mindedness. There must be Kannada pride; we must speak in Kannada; Kannada must grow, said Shri Basavalingappa, who has worked as the secretary of the Karnataka Unification Committee. However, he added that reading in English could also impart critical thinking skills, an independent sensibility and love for one’s country. Comparing Kannada books to boosa [cow fodder], the minister urged students and youth to disregard anyone who, under a veil of Kannada pride, asked them not to read English. Shri Basavalingappa, who spoke at length about New Waves, said that nobody in the orthodoxy whom he is protesting against has come forward to debate with him. If they can show with evidence and reason that I am wrong, I will become their follower, and if I show them otherwise, they should become mine, he said.

Notice the clickbait nature of the headline, and the selective positioning of Basavalingappa’s combative personality. The article could have chosen to highlight his bilingual stance, but it instead finds the most negative element in the mix to twist out of shape. Basavalingappa had no clue how momentous his speech would turn out to be. His original intentions became irrelevant, as the media and public began to create their own interpretations of his words, and one word in particular: boosa.

Boosa became the magic word that suddenly opened up longstanding fissures in Kannada society. Writers, politicians, students and activists began to voice their responses, creating a polarised arena, where English was pitted against Kannada, dalits and upper castes mobilised against each other, and the world of letters was suddenly forced into critical reflection. Violence erupted across the Mysore– Lost in Tran Bangalore region. Buses were burnt, donkeys were paraded on the streets, schools were shut down, effigies were burnt in front of the Vidhana Soudha, and police resorted to lathicharge to subdue angry mobs of mobilised students. BB’s statement had sent shockwaves across the state, setting the tone and tenor of social discourse for the tumultuous decade that the seventies will be.

Basavalingappa suspected that some of his own political colleagues had orchestrated his media trial. The matter reached such a fever pitch that Devaraj Urs ended up dropping him from his cabinet. Basavalingappa felt betrayed by his own comrades— but such is the nature of power politics. The controversy went on to make national headlines, and the ever blunt Khushwant Singh even wrote an editorial where he affirmed that boosa pervaded all regional literatures in the country, not just Kannada.

Basavalingappa later clarified his stance to journalists, saying;

We have become caught up in a fabricated controversy. Resolving this controversy itself will be a New Wave. Regarding this subject, what I wish to say is that literature should become richer. The textbooks we currently have do not possess the substance to make our students more courageous, patriotic and socially aware. They are still founded on conservatism, exploitation and are essentially dry material. Our students must read revolutionary books in other languages and enrich the Kannada world. Any literature without this is boosa—this is what I had said in that situation.

BB’s gesture was widely commended and appreciated by many, including writers like U.R. Ananthamurthy. In his autobiography, Ananthamurthy remembers the deeply anti-brahmin atmosphere during those years, when he too faced exclusion from some literary meetings. He viewed this prevailing temperament as a historical necessity, and tried not to take it personally. Ananthamurthy points to the cyclical nature of history, and the creative necessity of ensuring the unhindered turning of the wheel of time, which in this case meant a whole-hearted recognition of the dalit movement for dignity and respect. ‘With no movement, there is no vitality, and life is not creative.’ Ananthamurthy sees hypocrisy in the way society accepts rebellion as an abstract concept, but fails to tolerate actual rebellious ripples in the sociopolitical sphere. He asks his readers to inquire into why Basavalingappa would utter such words, and what reflections this throws up about society at large.

On the other side of the coin, dalits began to face increased oppression for their support of BB’s comments. The poet Siddalingaiah, who was yet to gain fame as a writer, used to be a frequent visitor to Mysore. He remembers how dalit students were picked out and beaten black and blue by angry upper-caste peers. Some principled reactionaries went so far as to accost teachers and students and smear vibhuti on their foreheads forcibly—the controversy had taken a religious tinge, another example of how caste and religion are well-nigh inseparable. Many dalits skipped town and returned to their villages to avoid the onslaught. Siddalingaiah and his comrades courted arrest through protest and landed up in jail, where, ironically enough, they were safer than their brothers-inarms out on the streets.

Siddalingaiah and his band of brothers (sisters were still few and far between) were the first generation of politically organised dalits in the state, and the boosa movement was their first war cry, like the cry of Vritra after enduring Indra’s vajra in the Ramanujan poem that begins this chapter. Siddalingaiah, who had grown up peering through the ‘slum windows’ of Srirampura in Bangalore, helped organise literacy campaigns in these deprived landscapes. I met communist veterans (all upper-caste men) in Bangalore who were part of these endeavours, actively teaching dalit children during weekends. One of them spoke a little mournfully about how Siddalingaiah had forgotten him upon rising to fame.

The movement was also aided by the fact that Chief Minister Devaraj Urs had fashioned a new paradigm in Karnataka politics by foregrounding leaders from backward castes, breaking the domination of vokkaligas and lingayats. He had also set in motion land reforms, and introduced a landmark reservation bill for backward classes under the stewardship of L.G. Havanur. This bill would greatly Lost in Tran influence the Mandal Commission a decade later. Thus, building on a larger political scaffolding, the dalit movement began organising a collective of artists and writers who sought to create an alternative world of letters, as well as a new media landscape, to confront the social elites who had cornered the narrative until then. With this, the individualised, psychoanalytic, libidinous, self-exploratory aesthetics of the Navya movement—in the ranks of which were those like U.R. Ananthamurthy and Gopalakrishna Adiga—began to transition into the sociopolitical protest movement known as dalit-bandaya. Communities that had been oppressed and excluded for centuries were finally entering the literary arena, and all the accumulated anger and rage spilt over into the fiery verses of poets like Siddalingaiah. One of the most famous poems from his first collection, Holemaadigara Haadu (Songs of the Holeya-Madigas), simply titled ‘A Song’, begins:

Bash them, kick them,

Skin those bastards alive!

God is one, they claim,

But build a different temple on each street! (translated by Maithreyi Karnoor)

These were verses designed to be sung in the public square, crafted to rankle the caste orthodoxy and plunge it into unbelief. The use of violent and vulgar language was a literary ploy, an outburst meant to challenge anybody who was socially coy. Siddalingaiah’s initial verses were all of this raging variety, though his work softens over time. His autobiography is uncharacteristically jolly for a dalit memoir, and his later verses too become gentler, more culturally welcoming, as in this one from a collection titled Hosa Kavitegalu (New Poems), published in 2000:

Let new vitality, new emotions,

be ushered in by a fresh Ugadi.

In the sunshine of love,

May Mother Earth forget herself.

Despite the desire for cosmopolitan English pedigree that boosa espoused, the dalit movement was decidedly down-to-earth and desi. This new literary environment brought with it entirely new forms and dialects of Kannada, and rich streams of metaphors and idioms which had once been confined to the alleyways of backward boondocks. Standardised in the nineteenth century by German missionaries and the arrival of the printing press, Kannada had remained a phenomenon of the literary elite throughout the early-twentieth-century renaissance. Now, the ‘saviraaru nadigalu’ (thousands of rivers—a phrase coined by Siddalingaiah) of regional expression were finally reaching the ocean of Kannada literature.

The writings of Devanura Mahadeva carried a dialect so uniquely rooted in the villages around Nanjanagud that it has been seriously asserted that his works must first be translated into Kannada so that they may become more widely readable. His late-eighties novel Kusumabale reaches back to the unique champu-desi hybridised flavour of fifteenth-century oral epics like Male Mahadeshwara Kavya and Manteswamy Kavya. These epics had very much been in dialogue with the sharanas of the twelfth century, as the similarities between Manteswamy and Allama Prabhu’s hagiographies demonstrate. They portrayed the various historical stages of civilisation through elaborate metaphors and imagery. Kusumabale employed this prose-poetry style to create a miniature epic that captures the realities of caste society in the modern world, and many, including D.R. Nagaraj, saw it as a genuine breakthrough in the aesthetic imagination of the dalit movement. A.K. Ramanujan had apparently expressed great desire to translate this work, but he doesn’t seem to have got around to it.

In the March of 1979, on the very day the annual Kannada Sahitya Sammelana was happening in the religious town of Dharmasthala, the rebel literary conference Bandaya Sahitya Sammelana was symbolically held in Bangalore. The two conferences symbolised two sides of the same coin of idealism—one being a conservative-mindedness that sought to preserve a comfortably prestigious past, and the latter a revolutionary consciousness in the process of Lost in Tran imagining a radical new future. When the poet Chennanna Walikar and his associates had asked Hampa Nagarajaiah, then president of the Kannada Sahitya Parishad, to allocate a special section of the conference for dalit writing, Nagarajaiah had sallied that there was no such thing as ‘dalita, balita, kalita’. Gopalakrishna Adiga, who had in the spring of his youth rejected the likes of Kuvempu and Masti and the old guard, was now, as head speaker at the conference in Dharmasthala, subjected to a similar rejection by the succeeding generation—definitely a Rama Bhima Soma moment, if ever there was one. The rebels made clear to the establishment that this was not a protest against an individual or an organisation, but a much larger one, against an entire system of values.

Excerpted with permission from Rama Bhima Soma: Cultural Investigations into Modern Karnataka, authored by Srikar Raghavan, Context- Westland Books.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.