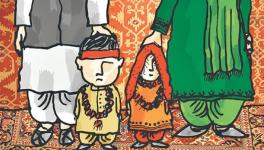

Poverty and the Pandemic are Fuelling ‘Trade’ in Children

A massive spurt in trafficking across several poverty-stricken districts in Bihar has seen village after village emptied of children. Bedaulia, Parasia, Naudiha, Chuabar, Vidyachuk, Amouna, these are just a few villages in Gaya district of Bihar where only a few children between the ages of 12-18 are still left.

Activists working in these districts confirm that the resumption of road and railway traffic, as also a big spike in unemployment following the Covid-19 pandemic, is forcing debt-ridden families to hand their children in bondage to traffickers in exchange for small sums of money.

Gaya-based advocate Neeraj Kashyap, who has been working with trafficked children for over a decade and has been travelling extensively through the region these villages are in over the past few weeks, says, “Parents are close to starvation and willing to let their children go to work in bangle factories in Rajasthan and other manufacturing hubs, in exchange for five to ten thousand rupees.”

Suresh Kumar, executive director of the Bihar-based NGO, Centre Direct, emphasises that since July traffickers have been coming to eastern Bihar in small pick-up trucks and luxury buses from Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, to ferry children to manufacturing hubs.

“They come armed with fake Aadhaar cards that show 12 and 13-year-olds to be 18 or 19. Since parents are facing deprivation and hunger, many travel with their children right up to factory sites so that the authorities do not become suspicious of the passengers,” said Kumar.

“We are aware of how these vulnerable children are being exploited post the pandemic and trying to stop this trafficking. On 19 August, we received a tip-off and intercepted one luxury bus on the outskirts of Rohtas with police help. We freed six young boys who were being taken to a bangle factory in Jaipur, but some were travelling with their relatives,” he said.

“Each bus is being hired at over Rs.3 lakh. That is the kind of investment factory owners are willing to make. Each trafficker is paid a minimum of Rs.1,000 per month for as long as the child works in the factory. The parents receive a measly Rs.2,000-3,000 every month for the child’s labour. It is difficult for us to match the muscle and money power of these traffickers,” says Kumar.

Also working to stop the blight of trafficking is the Salaam Balak Trust. Anjali Tewari, a group council member at the trust, says the organisation was recently tipped-off that on 7 September children were being brought by the Mahananda Express train to the old Delhi railway station.

“In the raid we freed 14 boys and got 10 traffickers arrested. The children were between 12 and 15 years old and had been brought to work as domestic labour in Delhi and Faridabad,” says Tewari who looks after the NCR region for the trust. The arrests were made under section 370 of the Indian Penal Code, which deals with prosecution of child trafficking offences.

Both the rescued children and the traffickers are from the same villages in Katihar, Munger and Madhubani districts of the state. Therefore, they had established close links with the parents of the trafficked children. Most traffickers, activists say, also succeed in getting bail and then return to trafficking. Penury-struck parents sooner or later, feel compelled to let children earn some money, even though abuse cannot be ruled out in these circumstances.

Tewari says that on 12 September, his organisation received another tip-off that a group of children were being brought to the Old Delhi Railway Station in the Capital. “We alerted police and were ready to nab the traffickers but they got wind of it and probably disembarked at Aligarh. They will probably remain in hiding there for a few days and then bring the boys into the National Capital Region by another means of transport,’ he says.

Tewari believes Childline, the helpline for children which is active in railway stations at Delhi and Ghaziabad has forced traffickers to change their strategy. Instead of arriving at these points they use Aligarh or another earlier station.

“The present spike in trafficking has come when only nine trains are arriving at Old Delhi Railway Station every day. The scenario when 300 trains start arriving here, as was the case prior to the pandemic, cannot be imagined,” he says.

Any humanitarian crisis, a cyclone, earthquake or a pandemic, leads to a jump in trafficking. Activists are alarmed at how the traffickers are able to out-manoeuvre the authorities in the present circumstances.

During the lockdown, transport was suspended and trafficking cases had declined. Rather, during May and June a reverse migration was taking place wherein children working in the factories of Gujarat and Rajasthan were escorted back to their villages by the traffickers from fear that if they were infected by Covid-19, the authorities may get alerted to the children living in confined spaces and coerced into working.

Patna-based Shilpa Singh, convenor of Bhumika Vihar, an NGO that helps rehabilitate trafficked youngsters, warns that the last three months have been terrible for the poorer socio-economic segment in Bihar. “Trafficking and forced migration of children has assumed astronomical proportions. In fact Bihar has gone back 20 years because there is no work and people have no money to buy food. Obviously, if traffickers offer Rs.50,000 to arrange the ‘marriage’ of young girls, or smaller sums for young boys to work somewhere, parents fall for the bait,” says Singh.

Bhumika Vihar, along with Campaign Against Child Trafficking, is presently organising a survey of 15 of the poorest flood-prone districts in Bihar to gauge the extent of this scourge. These districts, she says, are home to most migration.

Singh says, “It is unfortunate that the district authorities do not view trafficking with the seriousness it deserves. They see trafficking of child brides and of young boys as a social concern and not a crime. Therefore, this issue is not tackled with as much strictness,” she says.

And it is not just Bihar; the Calcutta High Court recently directed the West Bengal government to take steps to protect children in the wake of reports on the spike in trafficking, including for marriage, following cyclone Amphan and the pandemic. The Supreme Court has also sought a reply from the Centre and the National Disaster Management Authority on the spurt in trafficking after the lockdown.

Heenu Singh, regional centre head (North), Childline India, says, “With no jobs and no food for millions of families, the pandemic is turning out to be a golden period for traffickers. They are going to enjoy a free hand.”

The decision of the five state governments of Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat to relax labour laws has only emboldened traffickers and their customers, who employ hapless children. The future of the vulnerable children is being blighted for more and more families are being driven to destitution and it is all a matter of survival, of life and death.

The author is a freelance journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.