Shyam Benegal: Pioneer of Politically Engaged Cinema

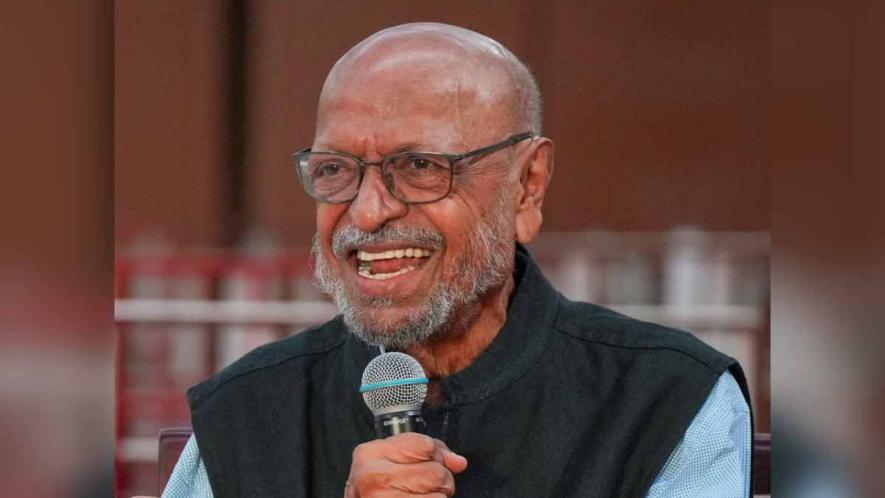

Shyam Benegal. Image Courtesy: PTI

Shyam Benegal (December 14, 1994 – December 20, 2024) happened to be a towering figure in Indian cinema, celebrated for pioneering a socially conscious and politically engaged cinematic style that redefined Hindi cinema. Emerging during the 1970s, a time when Indian society grappled with significant political and social upheaval, Benegal’s films introduced a fresh narrative voice -- one that probed deep into the realities of the marginalisd, challenged socio-political conventions, and inspired filmmakers across generations.

This article is a homage to Benegal’s monumental contributions to politically engaged Hindi cinema and explores how his legacy resonates in contemporary filmmaking. By tracing his journey, stylistic elements, and thematic preoccupations, we understand how his work shaped not only the parallel cinema movement but also influenced modern filmmakers who seek to balance art and activism.

The Genesis of a Revolutionary Filmmaker

In India, where cinema holds a unique place in the collective consciousness, certain filmmakers have dared to break free from formulaic narratives and embrace the medium as a canvas for activism and social critique. Among these, Benegal stands out as a pioneer who reshaped Hindi cinema with his uncompromising vision, politically charged narratives, and deep empathy for the human condition.

Emerging during the 1970s, a turbulent era in Indian history marked by political unrest, economic struggles, and rapid societal changes, Benegal’s work resonated with the aspirations and anxieties of a nation coming to terms with its identity. While Bollywood catered to the masses with escapist fare dominated by melodrama, song, and spectacle, Benegal charted a different course. His films illuminated the struggles of the marginalised, exposed systemic inequities, and gave a voice to the voiceless -- often in stark opposition to mainstream cinema’s celebration of fantasy and excess.

More than just a filmmaker, Benegal became a chronicler of India’s socio-political landscape, blending art and activism in ways that were both innovative and impactful. Through his films, he presented a cinema that was not only rooted in the country’s realities but also deeply reflective of its cultural, historical, and political complexities. His works addressed issues of caste, class, gender, and power with a rare sensitivity, offering audiences an unflinching gaze at the world around them.

Born in 1934 in Hyderabad, Benegal grew up in an India transitioning from colonial rule to independence. His formative years were marked by political turmoil and the socio-economic transformations of a nascent nation-state. These influences laid the foundation for his sensitivity to the struggles of the common man, an undercurrent that would define his oeuvre.

Benegal’s journey into cinema began with advertising, where he honed his storytelling skills through short films and documentaries. His first feature film, Ankur (1974), marked the beginning of a new era in Hindi cinema. This film, and the series of masterpieces that followed, became a cornerstone of what would be termed the "parallel cinema" movement.

In the 1970s, Hindi cinema largely revolved around escapist, melodramatic narratives dominated by the formulaic song-and-dance routine of commercial Bollywood. Parallel cinema, an alternative stream influenced by European auteurs and neorealist style, emerged as a counterpoint. It sought to depict stark socio-political realities with artistic integrity. Benegal was at the vanguard of this movement, and his films carved a unique niche by weaving personal stories with systemic critiques.

Benegal’s films delved into the intricacies of rural India, a stark contrast to Bollywood's urban-centric narratives. Ankur (1974), for instance, unflinchingly portrayed feudal oppression, caste discrimination, and gender inequalities through the lens of a young Dalit woman’s struggle for dignity. The realism of Ankur was both poetic and political, breaking new ground in Indian cinema. Likewise, in Nishant (1975), Benegal addressed the unchecked power of rural elites and its devastating impact on the lives of ordinary villagers. These films reflected not just individual oppression but systemic issues rooted in India’s socio-economic fabric.

Women’s Empowerment and Gender Politics

Benegal’s cinema has been a trailblazer in presenting women as complex, independent, and multi-dimensional characters. At a time when mainstream Hindi films often relegated women to the roles of supportive wives, sacrificial mothers, or decorative love interests, Benegal’s stories placed women at the centre, giving them agency and allowing them to challenge societal norms. His films explored the inner lives, struggles, and aspirations of women, making him a pioneer of feminist storytelling in Indian cinema.

One of the most striking features of Benegal’s work is his unwavering commitment to portraying women as protagonists, not merely as adjuncts to male narratives. His 1977 film, Bhumika, is a prime example of this approach. Based on the autobiography of Marathi stage and film actress Hansa Wadkar, the film delves into the life of Usha, played by Smita Patil, a woman caught between her professional ambition and personal struggles in a patriarchal society. Usha's journey of self-discovery is portrayed with sensitivity and depth, highlighting her vulnerability, resilience, and defiance against societal expectations.

Through Bhumika, Benegal not only critiques the oppressive structures of patriarchy but also explores the nuanced intersections of personal agency and systemic constraints. The film was a bold statement, challenging the narrative conventions of its time by presenting a woman who refuses to conform to the roles imposed upon her.

Similarly, Mandi (1983), one of Benegal’s most acclaimed films, tells the story of a brothel and the women who live and work there. The film, featuring powerhouse performances by Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil, turns the lens on the lives of sex workers, presenting them as individuals with dreams, fears, and a sense of solidarity. By humanising women often stigmatised and dismissed by society, he compels the audience to question their own biases and societal hypocrisies.

Benegal’s women cantered narratives are not limited to individual struggles; they also expose the systemic nature of gender oppression and the complicity of societal structures in sustaining it. In Ankur (1974), for instance, Lakshmi, played by Shabana Azmi, is a Dalit woman who becomes the target of exploitation by a privileged landowner. The film juxtaposes her dignity and strength against the moral cowardice of her oppressors, presenting a searing critique of the intersection of caste, class, and gender oppression.

Another noteworthy example is Kondura (1978), a film that explores the social and moral hypocrisies of a patriarchal society. Here, Benegal uses myth and folklore to critique the restrictive roles assigned to women and the ways in which male-dominated societies manipulate religious and cultural traditions to maintain control.

Benegal’s films also highlight the economic and social challenges faced by women, particularly in the context of labour and identity. Susman (1987) is a poignant exploration of the handloom industry and the struggles of artisans. While the film primarily focuses on the economic exploitation of weavers, it also sheds light on the role of women in sustaining their families and communities amid adversity. These women, often unacknowledged, are portrayed as the backbone of their households, navigating the dual burdens of labour and societal expectations.

In Manthan (1976), which revolves around the White Revolution and the establishment of milk cooperatives in rural India, women play a central role in the narrative. The film showcases their collective power and resilience in challenging oppressive systems and asserting their rights. It is through their empowerment that the cooperative movement gains momentum, making them agents of change in a male-dominated rural economy.

One of the defining aspects of Benegal’s women centred-storytelling is his collaboration with some of Indian cinema’s most iconic female actors, including Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, and Deepti Naval. These performers brought depth and authenticity to his narratives, embodying characters that were both rooted in reality and universally relatable.

Azmi and Patil, in particular, became synonymous with Benegal’s cinema, delivering some of their most memorable performances in his films. Their ability to bring emotional nuance and strength to their roles elevated the portrayal of women in Indian cinema, setting a benchmark for future storytellers.

In an industry still grappling with issues of gender bias and stereotyping, Benegal’s body of work stands testament to the power of cinema to question, challenge, and inspire change. Through his nuanced, empathetic, and unapologetically honest portrayal of women, Benegal redefined the possibilities of Indian cinema. His films continue to serve as a touchstone for feminist narratives, proving that cinema can be both a reflection of society and a force for its transformation.

Intersection of History and Contemporary Politics

Benegal’s cinema has always been deeply rooted in the socio-political realities of India. Beyond depicting the present, his works often delve into the past, using history as a lens to comment on contemporary issues. By revisiting pivotal moments and figures in India’s history, he crafts narratives that not only educate and inform but also provoke critical reflection on the enduring relevance of these events and ideas. His ability to intertwine historical exploration with contemporary political discourse sets him apart as a filmmaker deeply engaged with India’s identity and trajectory.

One of Benegal’s most ambitious projects in this realm was The Making of the Mahatma (1996). The film chronicles Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s transformative years in South Africa, a period often overshadowed by his later role in India’s independence struggle. By focusing on Gandhi’s early encounters with racism, inequality, and colonial exploitation, Benegal unpacks the evolution of his ideology of non-violence and civil disobedience.

Rather than deifying Gandhi, Benegal presents him as a human being shaped by his circumstances, personal struggles, and interactions with the oppressed. This nuanced portrayal demystifies the icon, making him relatable and, in turn, inspiring for contemporary audiences grappling with their own socio-political challenges. The film’s emphasis on Gandhi’s moral dilemmas and evolving strategies also serves as a subtle commentary on the importance of adaptability and self-reflection in leadership.

Similarly, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero (2005) sheds light on a controversial yet compelling figure in India’s freedom struggle. The portrayal of Bose navigates the complexities of his ideology, his disillusionment with mainstream nationalism, and his embrace of radical strategies to achieve independence. By presenting Bose in all his complexity, Benegal challenges the simplistic binaries often used to define historical figures, encouraging audiences to engage with history critically.

One of Benegal’s most significant contributions to Indian visual storytelling is the television series, Bharat Ek Khoj (1988). Based on Jawaharlal Nehru’s seminal work, The Discovery of India, the series spans centuries of Indian history, exploring the cultural, religious, and political developments that shaped the nation. Structured as a series of episodes, each focusing on a particular epoch or event, Bharat Ek Khoj offers a comprehensive yet accessible narrative of India’s evolution.

What makes Bharat Ek Khoj remarkable is its balance between historical fidelity and socio-political commentary. Through its exploration of episodes like the rise of Buddhism, the Bhakti and Sufi movements, and the colonial encounter, the series draws parallels between historical events and contemporary issues, such as communalism, caste discrimination, and gender inequality. Benegal’s use of storytelling, visuals, and performances transforms what could have been a dry historical account into a dynamic and engaging exploration of India’s pluralistic identity.

In a country where history is often politicised and selectively interpreted, Bharat Ek Khoj stands as a reminder of the richness and complexity of India’s past. The series remains relevant as it encourages viewers to embrace India’s diversity while critically examining the forces that threaten its unity. For example, the narrative frequently highlights the role of women in shaping India’s cultural and political landscape, from figures like Razia Sultana and Rani Lakshmibai to the women of the Bhakti and Sufi movements. This inclusive approach challenges the patriarchal lens through which history is often told, presenting a more holistic and egalitarian vision of India’s past.

Benegal’s historical narratives often engage with the legacies of colonialism and their continued impact on Indian society. In The Making of the Mahatma, for instance, he explores how colonial oppression shaped the political consciousness of both the colonisers and the colonised. This interrogation extends to his broader body of work, which frequently addresses the social and economic structures that colonialism left behind.

The Use of History to Comment on the Present

Benegal’s use of history is never purely retrospective. Instead, he employs historical narratives as a way of engaging with contemporary socio-political concerns. In Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero, for instance, Bose’s struggles against imperialism and his calls for radical change resonate with modern debates about leadership, nationalism, and the ethics of revolution. Similarly, The Making of the Mahatma emphasises the importance of non-violence and civil disobedience as tools for resistance, drawing implicit parallels to contemporary movements for social justice and human rights. By framing these historical narratives within a broader discourse on power, resistance, and identity, Benegal ensures their continued relevance for modern audiences.

Music and sound design play a significant role in Benegal’s historical works, with scores that evoke the cultural and temporal settings of the narratives. For instance, the use of traditional instruments and compositions in Bharat Ek Khoj adds depth to the storytelling, creating an immersive experience that transports viewers to the historical periods being depicted.

In an era marked by polarising debates about history and identity, Benegal’s work serves as a reminder of the importance of nuanced and inclusive storytelling. His films and series encourage audiences to see history not as a static record of the past but as a dynamic dialogue between the past and the present. His intersection of history and politics transcends the boundaries of cinema, offering a framework for understanding and addressing contemporary challenges. In tracing the legacy of Shyam Benegal’s historical works, we celebrate not just a filmmaker but a historian of the human condition, whose contributions continue to resonate in a world seeking to reconcile its past with its future.

Stylistic Signatures

Benegal’s films are a masterclass in subtlety, realism, and layered storytelling. His stylistic choices, both in form and content, set him apart from the commercial Bollywood formula and aligned him with the global tradition of socially conscious filmmakers. By employing a unique combination of minimalist aesthetics, collaborative craftsmanship, and narrative complexity, he redefined the language of Indian cinema. This section delves into the signature elements that characterise his work and continue to influence filmmakers.

Benegal’s films are marked by their understated visual style and restrained storytelling. Unlike mainstream Bollywood, which often relies on larger-than-life sets, melodrama, and grand musical numbers, Benegal embraced minimalism to reflect the raw and unembellished realities of his subjects. This approach is evident in his preference for naturalistic settings, which often include rural landscapes, humble homes, and workplaces that feel lived-in and authentic. For example, in Ankur (1974), the rural backdrop becomes a character in itself, reflecting the stark socioeconomic divide between the feudal landlords and the oppressed villagers. The cinematography captures the textures of the earth, the wear and tear of the villagers’ homes, and the intimate details of their daily lives. This realistic treatment is a hallmark of Benegal’s cinema, drawing viewers into his narratives without the distraction of artifice.

Benegal’s films owe much of their emotional depth and authenticity to his collaboration with some of India’s finest actors and theatre artists, such as Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri, and Amrish Puri, who became synonymous with his work and the parallel cinema movement as a whole. These actors, many of whom came from a theatre background, brought a naturalistic and nuanced approach to their performances. For instance, Azmi’s portrayal of Lakshmi in Ankur and Patil’s performance in Bhumika demonstrate an emotional depth rarely seen in mainstream cinema at the time. Their ability to inhabit characters from vastly different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds added authenticity and richness to Benegal’s narratives.

Music in Benegal’s films plays a supportive rather, used sparingly to heighten emotional or thematic moments. This restraint stands in stark contrast to the mainstream Bollywood tradition, where songs often interrupt the narrative. In Benegal’s films, music functions as an extension of the story, often rooted in the cultural or regional context of the film. In Manthan (1976), the song "Maro Gaam Katha Parey" reflects the ethos of rural India and the collective spirit of the milk cooperative movement. Similarly, in Bhumika, the use of classical music underscores the protagonist’s connection to her cultural and professional roots.

Benegal’s cinematographic style is rooted in simplicity and functionality, with an emphasis on serving the story rather than creating visual spectacle. His long-time collaboration with cinematographer Govind Nihalani resulted in aesthetically pleasing and deeply grounded visuals. In Nishant (1975), the camera often lingers on faces and spaces, creating an intimacy that draws the audience into the characters’ emotional and physical environments. The use of long takes and minimal cuts gives the audience time to absorb the details of the setting and the subtle shifts in the characters’ expressions. This deliberate pacing creates a sense of realism and emotional depth.

Benegal’s preference for natural lighting and on-location shooting adds to the authenticity of his films. Whether it is the arid landscapes of Ankur or the bustling interiors of Mandi (1983), the visual elements in his films are always rooted in the lived realities of the characters.

Benegal’s films often operate on multiple levels, combining personal stories with larger social, political, or historical themes. His narratives are layered with symbolism, inviting viewers to look beyond the surface to uncover deeper meanings. For example, in Ankur, the title itself meaning “seedling” - symbolises both hope and the beginning of change. The film’s exploration of caste and class dynamics is enriched by subtle visual cues, such as the contrast between the landlord’s luxurious home and the sparse living conditions of the villagers.

Similarly, in Manthan, the cooperative movement is not just about milk production but a metaphor for grassroots empowerment and the power of collective action. His use of visual and narrative metaphors often aligns with his broader themes, such as resistance, resilience, and the possibility of transformation. This multi-layered approach ensures that his films resonate on both an intellectual and emotional level.

One of Benegal’s most distinguishing stylistic features is his aversion to melodrama. His characters express their emotions with authenticity and subtlety, relying on small gestures and expressions rather than grandiose declarations. In Bhumika, for example, the protagonist’s turmoil is conveyed not through loud confrontations but through her quiet introspection and nuanced interactions with the people in her life. This understated approach makes the emotional moments in Benegal’s films all the more impactful, as they feel earned rather than manufactured.

Whether set in rural Maharashtra, South India, or Gujarat, his films pay meticulous attention to local customs, dialects, and cultural nuances. This regional specificity adds depth and realism to his narratives. For example, in Manthan, the characters speak a mix of Gujarati and Hindi, reflecting the linguistic diversity of the region. Similarly, in Kondura, the cultural practices and folklore of South India are woven seamlessly into the narrative, creating a rich tapestry of local life.

Underlying all of Benegal’s stylistic choices is his humanist ethos. His films are deeply empathetic, treating even flawed or antagonistic characters with compassion and understanding. This humanism is reflected in his visual style, which often focuses on faces, gestures, and intimate moments of connection.

By redefining the stylistic possibilities of Hindi cinema, Benegal has not only created a body of work that stands the test of time but also paved the way for future generations to explore the intersection of art, activism, and storytelling. His filmmaking is celebrated for its seamless integration of documentary aesthetics into narrative cinema.

Blurring Lines Between Fiction and Reality

A hallmark of Benegal’s filmmaking is his ability to weave documentary techniques into his feature films, grounding them in reality. By employing natural lighting, on-location shooting, and unembellished production design, he creates cinematic worlds that feel organic and lived-in. For instance, in Ankur (1974), Benegal’s use of real village settings and non-professional actors alongside seasoned performers lends the film an unmistakable air of authenticity. Similarly, Manthan (1976), funded by India’s National Dairy Development Board, incorporates a documentary approach to depict the grassroots milk cooperative movement. By focusing on the collective efforts of rural communities, the film blends fictional storytelling with real-world socio-economic transformations.

Beyond his feature films, Benegal has created an impressive body of work in the documentary format, exploring topics ranging from Indian art and culture to political and historical themes. One of his most notable works is Satyajit Ray: Filmmaker (1985), a documentary that provides an intimate look at the life and craft of India’s legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray. This National Award-winning film is a testament to Benegal’s ability to capture the essence of his subjects while paying homage to their contributions to art and culture.

His documentary approach has had a profound influence on the Indian parallel cinema movement. His works inspired a generation of filmmakers to adopt realism and socio-political engagement in their storytelling. Filmmakers like Anand Patwardhan (Jai Bhim Comrade, War and Peace) and Rakesh Sharma (Final Solution) have carried forward this tradition, using documentary techniques to highlight systemic injustices and amplify marginalised voices.

In a world where the boundaries between truth and fiction are increasingly blurred, Benegal’s approach to cinema remains a vital template for filmmakers seeking to reflect society’s complexities with honesty and integrity. His documentary style continues to influence contemporary Indian cinema, ensuring that his legacy endures in the works of those who use cinema as a tool for truth-telling and transformation.

Benegal’s Continued Influence on Contemporary Cinema

Shyam Benegal’s commitment to addressing complex social and political themes resonates strongly in the works of contemporary filmmakers. like Anurag Kashyap, Nagraj Manjule, Meghna Gulzar, and Zoya Akhtar among others. Nagraj Manjule’s Sairat (2016), a searing exploration of caste-based discrimination and forbidden love harken back to Benegal’s masterpieces such as Ankur and Nishant. Similarly, Meghna Gulzar’s Talvar (2015) and Raazi (2018) reflect Benegal’s influence in their blend of social critique and gripping storytelling. By using real-life events as a backdrop for their narratives, these films continue the tradition of politically and socially conscious cinema that Benegal helped establish.

Benegal’s films, deeply rooted in the socio-economic realities of rural and regional India, paved the way for contemporary filmmakers to explore narratives that go beyond urban-centric Bollywood stories. This influence is evident in the works of regional filmmakers who highlight local cultures, dialects, and struggles.

Nagraj Manjule’s Fandry (2013) and Sairat, Rima Das’s Village Rockstars (2017), and Lijo Jose Pellissery’s Jallikattu (2019) carry forward Benegal’s tradition of crafting stories that resonate with global audiences while remaining rooted in local realities. The revival of regional Indian cinema in recent years owes much to Benegal’s emphasis on authenticity and grassroots storytelling.

Films such as Article 15 (2019) by Anubhav Sinha, which addresses caste-based oppression, and Newton (2017) by Amit V. Masurkar, which critiques the bureaucracy of India’s democratic process, reflect Benegal’s legacy of tackling systemic issues through storytelling. These films, like Benegal’s Manthan and Susman, shine a light on institutional failings while celebrating the resilience of ordinary people. Directors like Hansal Mehta (Shahid, Aligarh) and Neeraj Ghaywan (Masaan) also adopt Benegal’s aesthetic in their emphasis on restrained performances and realistic settings.

At the core of Benegal’s legacy is his humanist approach to filmmaking - a belief in the power of empathy, dignity, and solidarity. Contemporary filmmakers like Shoojit Sircar (October, Piku) and Anand Gandhi (Ship of Theseus) reflect this ethos in their exploration of human connections, ethical dilemmas, and societal responsibilities.

Conclusion

As we mourn Benegal’s demise, his legacy continues to resonate, influencing contemporary filmmakers who grapple with similar questions of identity, justice, and representation in their work. His legacy is alive in the works of contemporary directors who dare to question, provoke, and inspire through their narratives. As long as cinema remains a medium for truth and change, the spirit of Shyam Benegal will continue to guide and inspire storytellers. In honouring his contributions, we celebrate the enduring relevance of politically engaged cinema in shaping society’s conscience and imagination. Fostering this continuity can be the only true tribute to him.

Pravin Raj Singh is an Associate Professor in the Department of English, Satyawati College, University of Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.