Not Just a Love Story?

Image Courtesy: The Hindu

We are used to clear-cut classifications in India, such as commercial versus art cinema or progressive films versus entertainment masala films. Even film-makers who are not shy of dealing with caste oppression or women’s issues can fall into the trap of catering only to particular cross-sections of the audience.

What puts Sekhar Kammula’s new Telugu film ‘Love Story’ in a class apart is his ability to portray intersectionality. Love Story can be seen as a film about caste dynamics, child sexual abuse, the evolving gender matrix in romantic relationships, city-village interactions, or, of course, love. Kammula successfully interweaves multiple dimensions without overburdening the film. The sum of parts is certainly greater than its individual components.

Imaginative Backdrop

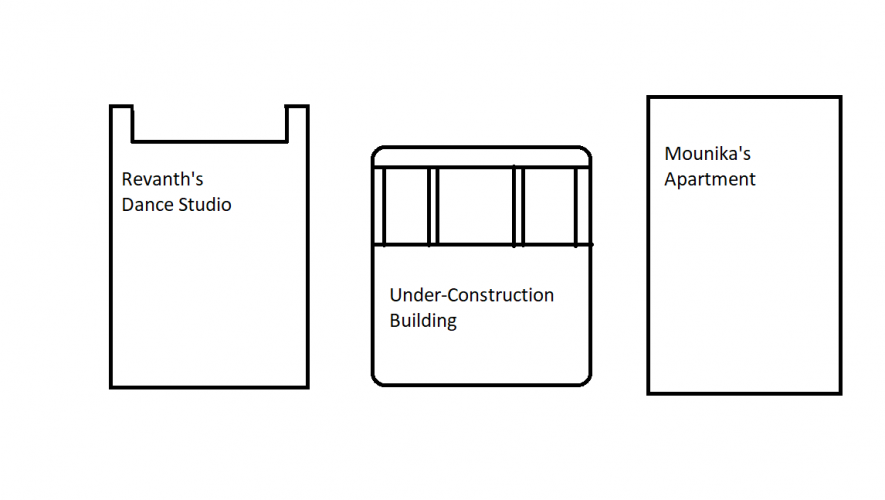

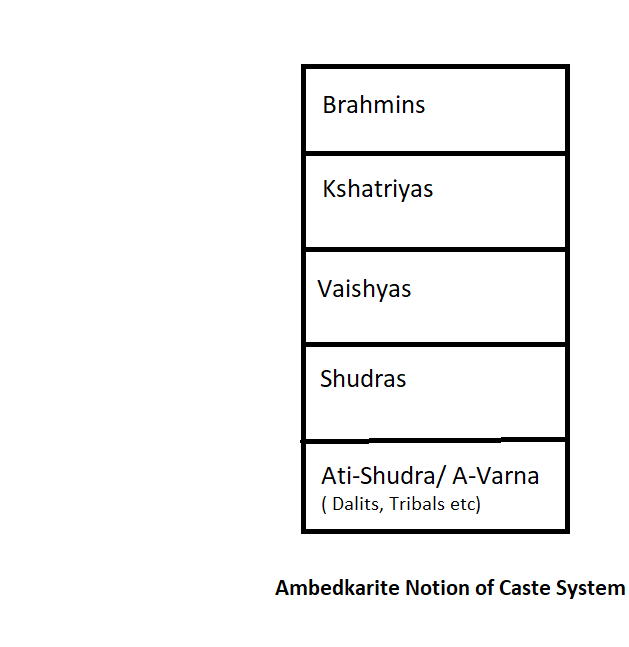

Revanth, a Dalit, and Mounika, belonging to an upper-caste zamindar background, often interact on the terraces of their respective apartments, separated by an under-construction structure. The setting reminds of how Dr BR Ambedkar described the caste system. He called it a “...multi-storied building without any staircase. Each floor is allotted to one caste. The floor on which one is born is also the floor on which one dies."

The architecture of their living spaces reflects the rigid caste structure. Revanth and Mounika, from either end of the caste spectrum, are represented by their separate residential quarters. Ambedkar’s argument resonates strongly here. He had said, “There are no ladders or stairs that connect different floors,” i.e., caste groups. The distance between Revanth and Mounika’s buildings signals the caste system’s denial of even a possibility for genuine dialogue between members from different social strata.

The under-construction structure between Revanth and Mounika’s apartments plays a unique symbolic role. It represents a meeting place for two people from very different backgrounds. The imagery of an under-construction building signifies a social order that is slowly being built where people can transcend the inhibitions of caste, class and gender. The fact that the building is under construction symbolises the incomplete but ongoing project of social transformation.

How and when will this project reach completion? Ambedkar had said inter-caste marriage is a way out. In other words, the coming together of two individuals can help break the rigid shackles of caste society by building bridges (or staircases) where none exist. That, however, requires a leap of faith, as Revanth realises at a crucial point in the film. When Mounika agrees to professional collaboration with Revanth, ecstatic, he leaps from his rooftop onto the roof of the under-construction building. This dangerous act with potentially fatal consequences signifies the risk involved in pursuing a better tomorrow.

The under-construction building is a zone of uncertainty where individuals willing to transcend their socially-assigned identities must be prepared to enter. When Mounika reaches the rooftop of the under-construction building to meet Revanth mid-way, she leaves behind all her pretence of being an engineer and zamindar. Revanth, too, gives up his false self-image of being a prosperous businessman. Atop the under-construction building, he no longer conceals his economic vulnerability from her. Only when individuals shed their sense of socio-economic pride and expose their human vulnerabilities—when they enter a zone of uncertainty—can something new and beautiful like love emerge.

Later, Mounika places a wooden plank between the under-construction building and Revanth’s building, making it possible to move seamlessly between the three buildings. It is a condition that Ambedkar called social endosmosis—wherein individuals from diverse social backgrounds can move between social positions without barriers. According to Ambedkar, the caste system makes social endosmosis impossible. The wooden plank represents individual efforts to overcome social obstacles by creating small spaces for social endosmosis.

Dalit Capitalism: Route to Emancipation?

Love Story treads a path different from contemporary films with Dalit lead characters such as ‘Karnan’, ‘Kaala’ and ‘Pariyerum Perumal (Tamil), ‘Court’ (Marathi) or Newton (Hindi). The new wave of Dalit cinema portrays stories where the Indian state either provides avenues for empowerment (Newton) or the state-market-society nexus victimises the Dalit community (Karnan, Kaala, Court). On this count, Love Story charts a different path, as Revanth is hopeful that engaging with market forces will liberate him.

As a child, Revanth experienced caste discrimination as well as economic deprivation. His mother tells him the discrimination will not end so long as they are economically dependent on upper castes. With a hope to transcend his socio-economic handicaps, Revanth starts a fitness enterprise around teaching Zumba. He even tells Mounika, “The future belongs to those who start businesses.” The genesis of his relationship with Mounika lies in economics: Mounika desperately seeks a job and stable income, which Revanth offers to her as he aspires to expand his business. Later, love blossoms between them. (Rationalist Govind Pansare had said that even love-based inter-caste relationships are possible only when the upward economic mobility of the non-elite castes challenges social inequalities.)

Economist Thomas Piketty has argued that we live in the era of “patrimonial capitalism”, wherein only those who inherit massive economic assets can prosper in contemporary capitalism. Revanth experiences the brunt of this reality. His family owns only half an acre of land, so, despite his entrepreneurial skills, he fails to mobilise capital to expand his business. His story exposes a primary myth of capitalism: anyone with a business idea, entrepreneurial mindset, and who works hard can prosper. Revanth ticks all three boxes yet falls short for no fault of his.

Another incident highlights a different aspect of the caste-based order: even economic empowerment fails to challenge caste inequity. Revanth and his mother visit Mounika’s home with a marriage proposal. They signal their upward economic mobility by wearing their best and finest clothes. As Revanth’s mother is about to tell Mounika’s mother about Revanth’s entrepreneurial successes, Mounika’s mother, indifferent and disinterested, simply walks away. The scene destroys another myth about capitalism: the wealthier you are, the more social respect you get. Economic empowerment is a necessary but insufficient condition to transcend the caste barrier.

Solidarity Overcomes Oppression

Love Story conveys an essential truth about love: it involves not only exploring and learning new things together but unlearning many things we imbibe from society and hold deep within us. Living in a patriarchal society makes us all patriarchal. The same applies to caste. In such conditions, love may emerge but cannot sustain. The movie depicts how deep-seated caste consciousness almost separates Revanth and Mounika. In one scene, Mounika angrily blurts out that “people like Revanth”, that is, people from lower castes, “should not be trusted”. Caste may go dormant but raises its ugly head even in a love relationship. So, how does one overcome what one is unaware of? Mounika claims she does not possess a “caste mentality”, but castelessness is a myth that only the privileged elite can believe in. An actual anti-caste stance involves collective action and genuine dialogue between those oppressed by caste and those who possess caste privileges but are willing to shed them.

Further, transcending caste requires action in the direction opposite to caste norms. Caste, based on notions of purity, requires members of elite castes to maintain a distance from ‘impure’ non-elite castes. The lead couple’s relationship, almost decimated by Mounika’s casteist remarks, is rejuvenated only by a radical act that transcends the possibility of distance.

Indeed, Mounika has experienced the oppression that a woman born in a patriarchal household in rural India faces, and worse. Her traumas have shaped her life, both private and public.

A defining question about Indian public life is the power dynamics between two people who are subject to different kinds of oppression. Does patriarchy override caste, or does caste superiority overpower patriarchy? Most people have experienced oppression and exploitation, so one difference is the degree of oppression. An upper-caste woman has to suffer from caste patriarchy but a lower caste man encounters a double axis of exploitation due to caste and class.

Can shared experiences of oppression help us transcend the desire to oppress, to “end the exploitation of humans by humans,” as Bhagat Singh dreamed? Normally, memories of oppression are perceived as too violent and disturbing to recount or re-tell. However, Kammula conveys that only we share experiences of oppression can we build solidarities and partnerships that can help us fight and transcend our exploitation. Then, traumas of the past have the potential to become the building blocks of a brighter future.

The author is an independent commentator. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.