Farm Suicides: Under-reported Realities of Indian Women Farmers

Image Courtesy: Hindustan Times

“I had to struggle eight long years to get one acre of land transferred to my name after the death of my husband,” said Vidya More, a 38-year-old woman farmer who had come to the national capital on Monday all the way from Osmananabad district of Maharashtra.

Vidya’s husband committed suicide in 2012 when she was only 30 years old following which, the liability they had, was on her shoulders. Even as the ex gratia compensation acts as an immediate relief to the families of the deceased, the government wasn’t ready to recognise the death of Vidya’s husband as a farm suicide.

Vidya is not the only one who had to face this issue. Korra Shantha, a 28-year-old woman farmer from Nalgonda district of Telangana tells a similar story.

“We do cultivation on a leased land. My husband committed suicide in 2018 and we have an outstanding debt of Rs 6 lakh. We applied for ex gratia with the help of local activists and have been trying to get this support. I have been to the local revenue office at the mandal and district level several times, but to no use so far. As my husband did not own land, I am not considered ‘eligible’ for getting ex gratia,” Shantha explained.

Vidya and Shantha were two among the group of 20 women farmers who have come to Delhi as part of a National Consultation co-organised by Mahila Kisan Adhikaar Manch (MAKAAM) and UN Women on the “Status of Women Farmers in Farm Suicide Families” where the affected women demanded a special support package from the government in the upcoming Budget itself. Women farmers from Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana were the part of consultation.

Widowed women often have to do several rounds of the local village offices and district level offices so that their husbands’ suicides can be recognised as farm suicides. There is no uniform policy and systems at each level maintain different sets of data on such suicides, said Kavitha Srenivasan from Karnataka, who works closely with the women farmers. Several state governments consider only land owners and land title holders as farmers while extending support after farm suicides. Tenant farmers, women farmers, etc. are usually not considered ‘eligible’.

“It is the duty of the respective [state] governments to figure out whether the suicides are farm suicides or not,” said Kavitha.

According to National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), as many as 3,53,803 farm suicides have taken place between 1995 and 2018 across the country. 85.81% of the deceased were male farmers, indicating that around 50,188 female farmers had ended their lives in this period. It also shows that a large number of women from farm households inherit massive debts after their husbands’ deaths. Despite this, plight of these women remains an issue that has not received much attention and coverage.

A recent study commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare (ISEC, August 2017) had found that the highest number of women farmers’ suicides was reported from Telangana, followed by Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal. But MAKAAM and scholars associated with it point out that these official numbers are often under-reported and conveniently manipulated.

Though a combination of ecological, economic and social crises trigger farm suicides, it is important to note that suicides were high amongst the landless and the small and marginal farmers. Many activists working on the ground report that the official figures are often manipulated by the ruling parties for political gain. “In the data, there are many inconsistencies pointed out by scholars, which show unreliability of such official figures, especially regarding re-categorisation of the farmer suicides,” said Kavitha.

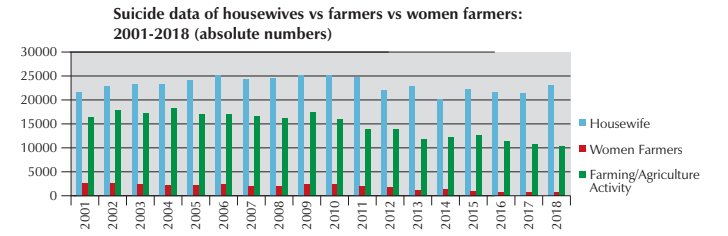

The Annual Report on Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India (ADSI) of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) publishes data on suicides of housewives as well—which is almost double the number of farm suicides. But the data does not give separate figures for ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ categories.

“It is therefore not possible to ascertain how many of the ‘suicides of housewives’ reported annually are from rural India, given that a large female workforce in rural India probably gets classified under unpaid ‘housewife’ category, but are actually farmers (as per an expansive definition given by the National Policy For Farmers, 2007). The same might apply to the category of female suicides under ‘daily wage earner’ in rural India. The figures under this category of female farm suicides is around 14% of the overall reported farm suicides,” says MAKAAAM.

For women farmers, denial of land rights and ineligibility for compensation in the name of technicalities stands as one of the frequent barriers as Vidya and Shantha mentioned. These women then have to continue with the same unsustainable farming the absence of social support.

Apart from this, there is wide variation in the ‘rehabilitation and resettlement’ packages given by different state governments. Andhra Pradesh provides compensation of Rs 7 lakh for each family where a farm suicide has occurred. On the other hand, Maharashtra, which records the highest number of farm suicides, gives only Rs 1 lakh ex gratia.

Consider the case of Maharashtra which had witnessed, according to NCRB, as much as 70,000 cases of farmer suicides since 1995. However, only around 30% of them were “eligible” for benefits. Kavitha points out that there is a contradiction between the NCRB data and Revenue Department data. The department has certain conditions for the beneficiaries; they must own their farmland, they must have taken an institutional loan form a bank and they should have suffered crop failure in that year. However, it does not necessarily recognise the accumulative nature of Indian agrarian debt crisis.

That is why the consortium, along with the affected women, demanded that the “criteria used to determine ‘farm suicides’ be revised and a uniform policy brought in, across states and departments (in police records, in agriculture and revenue departments etc.)”. The main criterion should be a suicide in a farming family, it said.

“Socially marginalized communities (Dalits and Adivasis) should get priority support in this policy package,” they asserted. The women farmers also demanded that there should not be any suppression of data.

Lastly, the women farmers along with MAKAAM, have urged the government to take action to prevent farm suicides including strict implementation of land reforms.

“For example, panchami lands in Tamil Nadu or Gairan, ceiling surplus lands in other states need to be identified and redistributed to dalits and other landless people. Along with this, all women farmers’ cases for recognition of rights to land under Forest Rights Act (FRA) or under other land succession laws be dealt with for recognition and documentation on urgent basis. Task force comprising women’s organisations, women lawyers and representatives of relevant departments be set up for this and for convergence of government services.”

Also read: Karnataka: Loan Waiver Money Deposited in Farmers’ Accounts Disappeared After LS Polls

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.