Afghanistan’s Tumultous Forty-Year Journey

Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

Historians believe that old sins have long shadows. For instance, the unjust and punitive terms of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 against Germany directly led to the rise of Nazi Germany whose revenge policy culminated in the Second World War.

Soviet intervention in Afghanistan in December 1979 was not born from old sins. Tsarist Russia maintained amicable relations with Durrani-ruled Afghanistan. Russia’s presence checked British ambitions in Afghanistan and Central Asia, enabling both Afghanistan and Central Asian khanates to preserve their shaky sovereignty. Conversely, for centuries, Afghanistan had problems with Iran, whose armies periodically overran this land. So Iran’s Islamic Revolution which commenced in 1978 cast a long shadow on Afghanistan’s destiny and ushered in a turmoil that continues today.

By the end of 1880, the British had retreated from Afghanistan after two humiliating defeats in the Afghan Wars. The ground had been laid for the Great Game in the preceding decade, in which Britain competed against Russia for pre-eminence in Afghanistan at the expense of Afghan interests. Later, in 1908, spurred by their mutual fear of German militarism in Central Asia, Britain and Russia felt compelled to enter into the Pamir Convention. Now Russia controlled much of the Pamir territory, up to the banks of the Oxus.

After the Bolshevik revolution, Russians engaged in peaceful penetration; they optimistically believed that poverty, inequality, a strong communist party and proximity to the Soviet Union would bring Afghanistan within the Soviet sphere. They did not realise that Afghanistan, despite being poor and feudal, was fiercely independent.

The end of British rule in India and the disastrous Partition in 1947 also affected Afghanistan. The Afghans protested against the arbitrary Durand Line created by Britain and agreed to by King Abdur Rahman Khan. This division of territory was intended to weaken Afghanistan and strengthen Pakistan. The Soviet Union, however, supported Afghanistan and condemned the Durand Line as another act of British Imperialism.

King Zahir Shah established the Afghan Constitution in 1950. He wanted friendship with both the United States of America (US) and the Soviet Union. As Pakistan’s ally, the US refused economic aid to Afghanistan, so it turned to the Soviet Union, which readily offered economic and military aid. The Russians assisted the Afghans to build roads between Kabul, Herat and Kandahar that would outflank the Hindu Kush, constructed tunnels, built silos for storing food grain and invested in small-scale industries. It concluded a $25 million arms deal with Afghanistan and gave an economic aid package worth $550 million. With Soviet assistance the Helmand Valley project was revived, power generation began in the Duranta Dam.

Afghan defence personnel were trained in Russia, military equipments were supplied by Russia, 40% of Afghan exports went to Russia. Young Afghan men and women received medical and technical education in Soviet universities, and Russian language came into wide use.

With Russian help, education received an impetus in the 1960s and seventies. Literacy rates increased, even among women. Girls attended school, half the university students were women, 40% of doctors were women, 70% were teachers and 30% were civil servants, some were judges and members of parliament. Afghanistan seemed on the road to modernity and progress.

Soviet diplomacy triumphed in the non-Western world during 1957-1978, and was particularly successful in Afghanistan where Russia gained goodwill through aid and amity. Encircled by US allies, Russia invested in a stable and friendly Afghanistan.

When Iran’s alliance with the US ended in February 1979, the Soviet Union was the first nation to recognise the Islamic Republic. But it swiftly saw the menace of Islamic fundamentalism that aimed to incite religious strife in the Muslim Central Asian republics of the Soviet Union. A call to Islamic fundamentalism could dismember the Soviet Union.

Having lost its base in Iran, the US wanted to ensure that Russia would not have influence there and sent messages to Iranian leaders that the ‘infidel’ Soviets wanted to stir rebellion among minorities to weaken the Islamic republic and that Iran’s real enemy was not American imperialism but the Soviet Union and a pro-Soviet Afghanistan.

While the Ayatollahs were enforcing Islamic fervour in Iran in 1979, the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan or PDPA led by Nur Mohammed Taraki, Hafizullah Amin and Babrak Karmal gathered strength. The party received full support from Moscow. When food shortages led to riots and student agitation in 1977, Premier Daoud suspected the hand of the PDPA in fomenting unrest, and gave orders for the arrest of its leaders.

On 28 April 1978, Afghan army officers carried out a bloody coup d’etat that overthrew the government of Prince Daoud, cousin of the deposed King Zahir Shah, the last of the Durrani dynasty. The Revolutionary Council of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan formed the government. It was dominated by the leftist Khalq faction. The moderate Parchami group was side-lined. Nur Mohammed Taraki became the president, and Amin and Karmal his deputies.

PDPA leaders attempted to modernise Afghan society, which was steeped in inequality. Taraki’s socialist government planned land reforms to help the exploited peasantry, abolish usury, improve the legal status and rights of Afghan women.

Afghan political leaders wanted to telescope time and take the country into the modern age. Rural people were satisfied with the subsidies for cottage industries; the Darunta Dam situated on the Kabul River built by Russians in the 1960s supplied 40-45 megawatts electricity; the Panjshir Valley project provided water for irrigation and electricity generation. Further east was the Daury Project. The Soviet government continued projects in the Helmand, constructed a railroad over Amu Darya to Pol-e-Khomi and Kabul, Towaragondi and Kheyrabad; they laid the natural gas pipelines out of Sheberghan into Turkestan and Tajikistan.

Warlords and tribal leaders watched the modernisation, and their grip loosening, with growing dismay. They allied with the clergy to intimidate the workers and peasantry, warning them to not support the socialist government. Iran stirred the cauldron by sending mullahs. Pakistan, the traditional foe, did not want a strong Afghan government either and incited insurrections along Afghanistan’s eastern border. Educated, professional Afghans were deeply anxious about the situation.

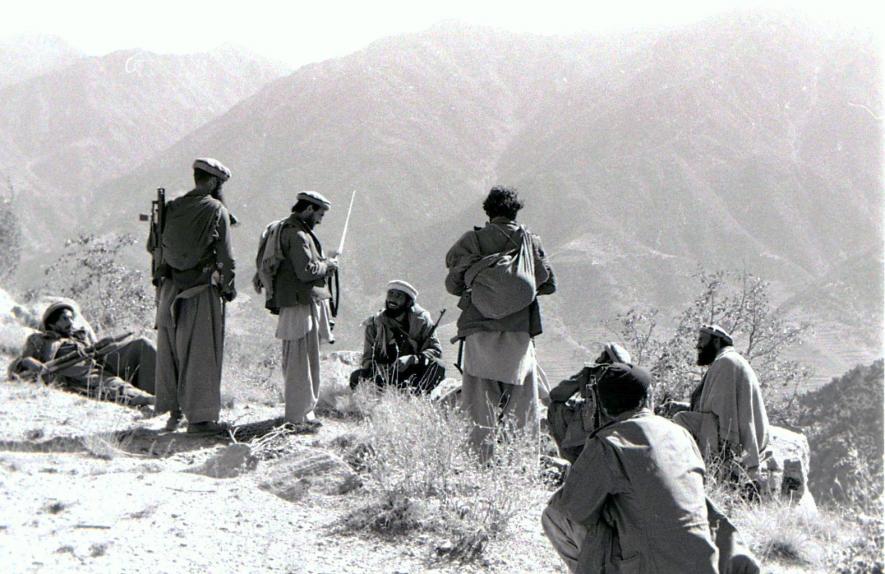

While Taraki’s government struggled with socio-economic problems, Muslim clerics sent followers to foment civic strife. Wiser after Vietnam War, the US decided against direct intervention in Afghanistan. Instead, it directed Pakistan’s Inter Service Intelligence (ISI) to train unemployed youth who were anointed as mujahidin, ‘warriors of god’—a travesty of the word god. Their religiosity was fuelled by some one billion US dollars. The US armed and funded them while Pakistan and Iran incited them with the banner of Islam.

The ISI received $3 billion dollars to train mujahidin-terrorists. They received C4 plastic explosives, long-range sniper rifles, wire-guided anti-tank missiles, anti-aircraft missiles and external satellites, reconnaissance data on the location of Soviet targets. Some 90,000 Afghan guerrillas and another 100,000 reserve were trained in Pakistan and equipped with 122 mm howitzers, AGS-17, grenade launchers, M-4L 82 mm mortars, SA-7 surface-to-air missiles.

Armed bands from Iran to the west and Pakistan to the east crossed the porous border with weapons and money to incite rebellion against the new People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) government. Training camps were established in Pakistan, where unemployed young Afghans were trained in terrorist warfare.

The lethal cocktail for an uprising—unemployment, inflation and food shortage—was present. Unaccustomed to governance, members of the PDPA adopted repressive measures. Many were corrupt. The ruthless deputy president Amin, who controlled the KHAD (Khademate Ettelate Dowlati or secret police) began eliminating opponents. Afghan army officers, the main support of the PDPA were alienated by the sudden arrests, summary trials, and disappearance of anyone suspected of deviation.

Instigated by Iranian clergy, serious disturbances engulfed Herat town in mid-1979. Led by senior commanders, several army units mutinied, taking the Afghan government by surprise, and joined the jihadists. They murdered Soviet advisers. The ISI also collaborated with Chinese agents to undermine Russian influence; China wanted to be the paramount power in Asia, which she could not be so long as Central Asia was part of the USSR.

Taraki’s government refused Moscow’s advice to involve the Afghan people in governance. The repressive acts of PDPA leaders strengthened feudal chiefs, mujahidin and mullah-mentors. Unable to control the growing unrest, Taraki requested Moscow for military intervention.

Soviet Ambassador F Tabayev informed the Kremlin: “Time is running out for the PDPA. Moscow would have to formulate a policy quickly.”

Soviet Foreign Minister Gromyko saw the danger of Afghanistan falling to Iran’s jihad, and the dangerous repercussions this would have on the unity of the Soviet Union with its Muslim Central Asian Republics. Nur Mohammed Taraki went to Moscow to plead for Soviet military intervention. Soviet leaders sternly advised Taraki to concentrate on economic development and social justice for his compatriots. They sent large shipments of wheat and agreed to send MI-24 helicopters, armoured transport and military infantry vehicles, modern communication and promised to train military personnel including pilots. Moscow’s counsel for moderation fell upon deaf ears. The situation deteriorated swiftly between May and November 1979. The immoderation of Taraki and Amin led to scattered uprisings in rural Afghanistan. There was terror and turmoil.

Amin began negotiating with the US for support to seize power. He offered the US military bases on the borders of the Soviet Central Asian Republics, in return for their support to become president. Simultaneously, Amin began dialogues with fundamentalist forces in Iran and Pakistani military personnel, ready to renounce all claims to Pashtunistan in return for Pakistani assistance.

When Soviet intelligence operatives informed Kremlin, it considered replacing the Khalq faction by the moderate Parchams led by Babrak Karmal, with the support of Tabayev and his advisers. But Moscow shied away. This tragic vacillation changed the course of history in Afghanistan and future world events.

In July 1979, Amin seized power in a violent coup and had his colleague and friend Mohammed Taraki murdered. Between July and November 1979 Amin’s repressive policies compelled some 11,000 Afghans into exile. Another 10,000 were killed. The Soviet Union sent in more observers and advisers to check the mounting chaos; and expressed concern for “the situation in Iran and the spark of religious fanaticism in parts of the Middle East as the underlying cause of the anti-Kabul agitation.”

There were rumours that the US and Pakistan were planning to install a US-backed regime in Kabul. Iranian jihadis were planning to foment trouble in the Soviet Central Asian Republics and threaten Russia, and finally there were fears that with Pakistan’s assistance, the US would occupy Afghanistan and arrive at Russia’s doorstep.

Had Russia’s relations with America been more amicable, the two powers could have arrived at a consensus regarding Iran and Afghanistan. Had the United States seen the real danger of Islamic fundamentalism, the tragic events of West Asia would have been averted. Instead, US president Jimmy Carter backtracked on arms reduction and began fortifying NATO presences all around the Soviet Union, intensifying the Cold War.

In mid-December 1979 the Press Corps in Kabul speculated on an imminent Soviet intervention. Few could predict the consequences of the intervention that would unfold over the next two decades. The same mujahidin that the US had trained and armed to fight Russia would carry Islamic jihad into the heart of America and Europe. Dark events of the future lay hidden behind gaudy slogans of democracy.

On 12 December 1979, Soviet leaders sent some 75,000 troops into Afghanistan. Two days later the General Staff operative team under Marshal Sergey Akhromeyev was on the Afghan frontier in Termez, Uzbekistan. On 18 December, members of an operational team arrived at the Bagram Air Force base in Kabul.

Tabayev authorised the official Soviet news agency to inform the international media of the dual dangers facing Afghanistan and the Soviet Union. A representative of Agentstvo Pechati Novosti informed Kabul-based journalists at the conference hall of Hotel Kabul: “We have confirmed information that CIA and ISI are financing bands of mercenaries to create disturbances and violence in Afghanistan…Their aim is to remove the pro-Soviet regime and replace it with an anti-Soviet regime that would allow Afghanistan to be the staging ground for aggression against the Soviet Union which has a 2000 kilometer long border with Afghanistan… Decision has been made to deploy several contingents of Soviet troops stationed in the southern regions of the country to the territory of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan in order to give international aid to the friendly Afghan people and also to create favourable conditions to interdict possible anti-Afghan actions from neighbouring countries…”

The international response to Soviet intervention varied. There were diverse responses from the non-aligned nations to Soviet intervention in Afghanistan. Former colonies of European powers chose not to oppose Soviet policy because they had received moral and sometimes armed support from the Soviet Union during their liberation struggles. At the height of hostilities, India silently supported the Afghan government and offered humanitarian aid. A few Muslim nations issued adverse remarks. Warsaw Pact members, except Rumania [now Romania], supported Russia.

The US feared that Soviet presence would challenge its influence in the Persian Gulf region, especially as the Soviet air base outside Kandahar was 30 minutes flying time away for a strike aircraft or naval bomber to the Persian Gulf. The US believed that having established a base in Afghanistan, the Soviet Union could gain access to the Indian Ocean region where American allies, Thailand and Philippines, are located.

Zbignew Brezenski, USA’s numbskull of a security adviser, publicly declared that he has instructed Pakistan for a joint and coordinated response, “the purpose of which would be to make the Soviets bleed for as much and as long as is possible; and we engaged in that effort in a collaborative sense with the Saudis, the Egyptians, the British, the Chinese, and we started providing weapons to the Mujahidin, from various sources…”

Pakistan’s military dictator Zia-ul-Haq obeyed the US diktat. Director General of ISI at the time, General Rahman, suggested a covert operation in Afghanistan by inciting and arming Islamic fanatics. “Kabul must burn!” he declared. This was Pakistan’s revenge for Soviet support to India during the Indo-Pakistan war of 1971.

Thus, began a decade of violence and destruction. Dollars and jihadi sentiments made the Afghan rebels pawns in a disastrous game which shattered their country.

The mujahidin did not engage in direct combat; they relied on sabotage. While targeting Soviet bases they also blew up power transmission lines, oil pipelines, radio stations, government offices and public places such as hotels, cinema houses even hospitals. They mined the land, endangering the Afghan people whom they claimed to be fighting for. They made local inhabitants, even children, assist them. They killed indiscriminately—passengers in airplanes and buses, students, teachers, government officials. The mujahidin were the enemies of the Afghan people.

The war in Afghanistan did not alienate Central Asian Muslims. There were no instances of Soviet Central Asian soldiers defecting to the Muslim mujahidin in Afghanistan.

The Soviet government had replaced the cruel lunatic, Amin, by the moderate Babrak Karmal and Najibullah. Soviet and Afghan armies had begun to bring a semblance of stability and order to the troubled land. Alarmed at the prospect of permanent Soviet presence in oil rich West Asia, Stinger missiles were given to the mujahidin. They began to rout the Soviet and Afghan national army.

Two decades later Hilary Clinton, then US Secretary of State, declared that supplying missiles and other advanced weaponry to the Afghan terrorists was the greatest blunder in recent US foreign policy. Today, US President Donald Trump has said that US aid to the mujahidin proved disastrous for the world.

From 1987 onwards, Soviet leaders began to formulate an “exit strategy”. This entailed training the Afghan defence forces to combat the mujahidin without Soviet armed assistance. The Soviet decision to gradually withdraw caused anxiety in the Afghan government. Without active Soviet armed assistance, they were unable to withstand the fierce mujahidin terrorist tactics, the skirmishes at Arghanbad, Paktia and Zhawar showed.

As Soviet forces began withdrawing, the US stepped up arms supply to the mujahidin-terrorist outfits; Ahmed Shah Masood’s contingent unleashed greater violence and casualties, especially on civilians. Operation Cyclone made America an active participant in the violence in Afghanistan. The ill-conceived and fatal Reagan Doctrine escalated the violence. The Central Intelligence Agency funded bin Laden and other Arab volunteers to assist the mujahidin against the ‘infidel’ Russians.

Thus Al-Qaeda was born.

A decade later, bin Laden turned his implacable wrath on ‘infidel’ Americans.

These developments were simultaneous with the advent of Mikhail Gorbachev as ruler of the Soviet Union. He wanted to usher in a new era in Soviet foreign and domestic policy. Unfortunately, he embarked on a policy of appeasement without considering the consequences. Economic reforms, Glasnost and Perestroika were fine concepts but negotiating from a position of weakness did not enhance Soviet prestige or position. He hoped to end the Cold War by signing the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in the US. His gravest miscalculation was to withdraw from Eastern Europe without a formal treaty to guarantee that NATO would not intrude in this area. Shortly after the Soviet withdrawal from Eastern Europe, USA and NATO reneged on verbal assurances and made partners of former Warsaw Pact members, followed by violent dismemberment of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia.

Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan began in May 1988 and continued by stages up to February 1989. Their departure left the field free for the terrorist-mujahidin, whom the Afghan national army had difficulties resisting. Karmal was unable to consolidate the position of the government. Several cities and provinces were abandoned to the mujahidin, which soon reinvented itself as the infamous Taliban. The next president, Mohammed Najibullah, introduced a new Constitution and embarked on a policy of national reconciliation, bringing a measure of stability. A United Nations negotiator, Diego Cordova formulated the Geneva Accord, which the Soviet Union, the USA and Afghanistan signed.

Military historians have been baffled by the reverses sustained by the Soviet army in the war against Afghan mujahidin. The valiant Red Army—that turned the tide of the war against the formidable forces of Nazi Germany, that had swept across hostile terrain and minefields until arriving in Berlin to raise the flag of the USSR on the roof of the Reichstag—was defeated by an uneducated mujahidin inspired not so much by religious fervour as the lure of dollars provided by its opponents.

It is the circumstances that were completely different, as was the nature of warfare. Two professional European armies of Russia and Germany fought in the Second World War on familiar European soil, both trained in conventional and large-scale warfare. In the unfamiliar, formidable Afghan terrain, the Soviet forces could not outwit the mujahidin and their guerrilla warfare. The mujahidin would retreat into hide-outs; the heavy Soviet tanks and columns announced their presence, with perilous consequences. Soviet soldiers were conscripts, not always well-trained. They did not have the commitment that the Russian soldiers had when fighting for defence of a Mother Russia invaded during a world war. The elite teams such as Spetsnaz and VDV were inadequate in numbers and too thinly spread across hazardous terrain. Success in guerrilla warfare requires effective counter intelligence. Soviet forces relied on radio interceptions for information gathering rather than infiltration into mujahidin ranks. The Cold War was a White Man’s war where Russians and Americans could penetrate each other’s citadels and espionage systems. This was not possible for Soviet operatives in Afghanistan where the tribal ‘bush’ telegraph operated.

All would-be conquerors of Afghanistan have been defeated not so much by the valour of its natives but by the unforgiving terrain that defeats open warfare. The Afghans know the intricacies of their mountain passes.

Finally, the inherent contradiction of the intervention removed the commitment that is essential for victory. The Soviet Union had encouraged and supported wars of liberation against colonial powers. Afghanistan was different. It was a civil war between a pro-Soviet regime and US-China-Pakistan-sponsored rebels. Despite the pleas of two Afghan presidents, Taraki and Amin, Soviet leaders resisted intervention through 1979, until the southern frontiers of the Soviet Union and nuclear installations there were threatened by Islamic fundamentalism. Support of the regime became an evil necessity dictated by the Soviet Union’s own security needs.

Had the USA not decided to “make Afghanistan Soviet Union’s Vietnam”, the untold misery and displacement of Afghan people, destruction of the nation’s infrastructure, heavy casualties of Soviet army personnel and of the Afghan people would have been avoided. The tragic scenario continues today.

Most of all, there would have been no mujahidin, al Qaeda, Jubbar al-Nusra and Taliban, who are soaking the good earth in the blood of the innocent. Like Attila and his Huns, the Taliban are the scourge of God. Like the Huns, these assassins will also disappear. And civilisation will reclaim humanity.

The author is a retired civil servant who writes on international relations. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.