Only 6.4% of Indian Children Get Minimum Adequate Diet, Says Study

The Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey (CNNS), the first ever nationally representative nutrition survey of children and adolescents in India was released by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) on Monday, October 7. The survey has found that shockingly, only 6.4% of children under the age of two years get minimum acceptable diet in India. The study also found that 33% of Indian children aged 0-4 years were underweight, close to one quarter of new-borns were wasted, and 35% of Indian children aged 0-4 years were stunted.

The survey pointed out, “Malnutrition has been identified as one of the principal causes limiting India’s global economic potential. The remaining socio-economic inequalities have stifled more equitable growth and subsequent economic expansion. While fertility and malnutrition declined in the past two decades, noncommunicable diseases (NCD) have arisen as major causes of death.”

The CNNS was conducted in all 30 states of India using a multi-stage survey design covering rural and urban households. The survey collected data from three target population groups: pre-schoolers (0-4 years), school-age children (5-9 years) and adolescents (10-19 years).

Dietary Trends

The survey pointed out, “A nutritionally-adequate diet during the first two years of life is necessary for optimal growth, health and development of children. Dietary diversity is a proxy for nutrient adequacy of the diet. Insufficient dietary diversity and meal frequency play a key role in nutritional deficiencies among infants and young children, leading to increased risks of childhood morbidity and mortality.”

It added, “The three core indicators of minimum dietary diversity, minimum meal frequency, and minimum acceptable diet are recommended by the WHO to assess the quality of complementary feeding practices for children aged 6 to 23 months.”

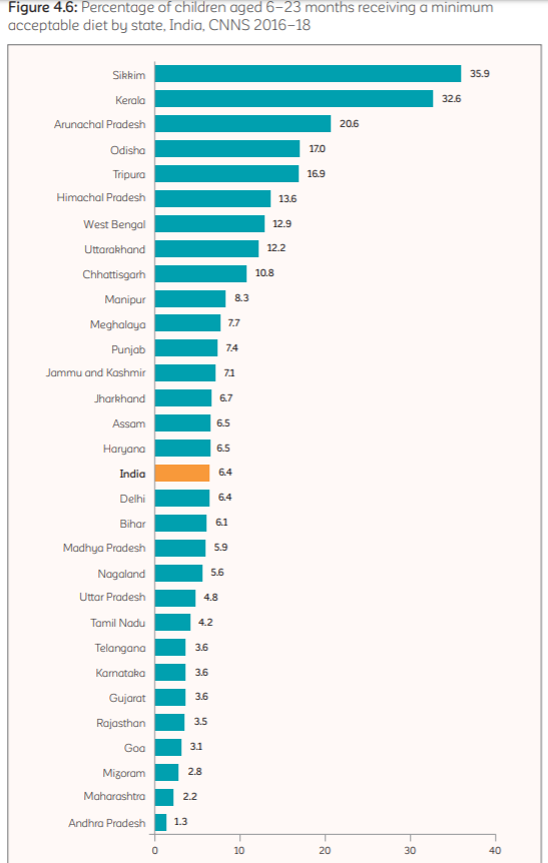

It was found in the survey that only 6.4% of children under the age of two years get minimum acceptable diet in India. At 35.9%, the percentage is highest for Sikkim, followed by Kerala (32.6%), and Arunachal Pradesh (20.6%). At the other end of the spectrum are Mizoram (2.8%), Maharashtra (2.2%), and Andhra Pradesh (1.3%). At 3.5%, Rajasthan follows Gujarat, Karnataka, and Telangana (all 3.6%), which rank close to the tail end of the list.

It also found that only 21% of the children between 6-23 months of age received that minimum dietary diversity. The proportion was the highest in Meghalaya (62.3%), followed by Sikkim (58.8%), Kerala (52.8%), and West Bengal (42.9%). Ranking towards the end of the list were Bihar (13.2%), Andhra Pradesh (11.9%), Rajasthan and Jaharkhand (both 11.6%).

Percentage of children under two years of age who received food minimum number of meals per day across the country was found to be 41.9%. The states with the lowest proportion of children fulfilling minimum meal frequency were Goa (23%), Punjab (22.6%) and Andhra Pradesh (22.0%).

The survey also pointed out that among this age group, only 8.6% of the children were fed iron-rich food. At 0.9%, the proportion was shockingly low in Haryana. Meghalaya, at 54.3%, ranked at the top of the list, followed by Manipur (39.4%), Kerala (37.4%), and Arunachal Pradesh (34.7%)

Referring to the dietary patterns of children between two and four years of age, CNNS said, “Child food consumption patterns varied by the mother’s schooling status and household wealth. The proportion of children aged 2 to 4 years consuming dairy products, eggs, and other fruits and vegetables increased with the mother’s education level and household wealth status.” It added, “A higher proportion of children residing in urban compared to rural areas consumed dairy products (74% vs. 58%), eggs (22% vs. 14%), and other fruits and vegetables (50% vs. 38%).”

The survey pointed out that food consumption patterns were similar between male and female school-age children (5-9 years) and adolescents (10-19 years), except for milk or curd and eggs. It said, “Among adolescents, a higher proportion of males consumed milk or curd and eggs, compared to females, with only a slight difference among school-age children.”

It found that food consumption patterns varied by the mother’s schooling status and household wealth among both school-age children and adolescents. The consumption of milk or curd, fruits, eggs, and fish or chicken or meat increased with higher levels of maternal schooling and household wealth.

Clinical Effects of Malnutrition

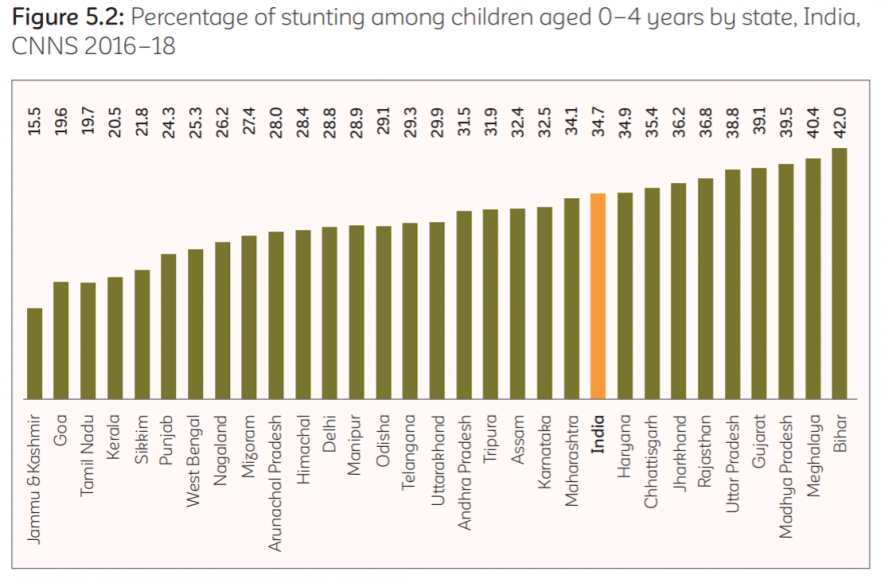

The survey found that 34.7% of Indian children aged 0-4 years were stunted. A number of the most populous states including Bihar (42%), Madhya Pradesh (39.5%), Uttar Pradesh (38.8%), and Rajasthan (36.8%) had a high stunting prevalence. The lowest prevalence of stunting was found in Goa (19.6%) and Jammu and Kashmir (15.5%).

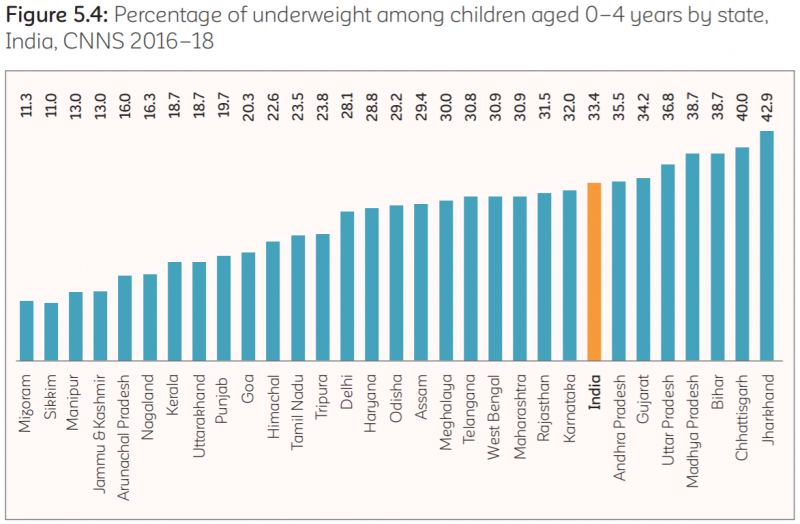

As per CNNS, 33.4% of Indian children aged 0-4 years were underweight. Many states in the Northeast of India, such as Sikkim (11%), Mizoram (11.3%), Manipur (13%), Arunachal Pradesh (16%) and Nagaland (16.3), had the lowest prevalence of underweight. Jammu and Kashmir (13%), Kerala and Uttarakhand (both 18.7%) ranked towards the top of the list. A higher prevalence of stunting in under-fives was found in rural areas (37%) compared to urban areas (27%). Also, children in the poorest wealth quintile were more likely to be stunted (49%), as compared to 19% in the richest quintile.

The states with the highest prevalence of underweight were Bihar (38.7%), Chhattisgarh (40%), Madhya Pradesh (38.7%) and Jharkhand (42.9%). The survey found that rural areas had higher prevalence of underweight in children under five (36%) compared to urban areas (26%). Scheduled tribes had the highest prevalence of underweight (42%) as compared to scheduled castes (36%), other backward classes (33%), and other groups (27%). Similar to stunting, children under five from the poorest wealth quintile had a prevalence of underweight more than twice that of the children from households in the richest wealth quintile (48% vs. 19%).

Overall, 17% of Indian children of age 0-4 years were wasted. High prevalence states included Madhya Pradesh (19.6%), West Bengal (20.1%), Tamil Nadu (21%), and Jharkhand (29.1%). The states with the lowest prevalence of under-five wasting were Manipur (6%), Mizoram (5.8%) and Uttarakhand (5.9%). A higher proportion of children under five years of age in the poorest wealth quintile were wasted (21%) compared to those in the highest wealth quintile (13%).

The survey said, “Stunting and underweight prevalence were both about 7% in new-born children, with a steady increase in both indicators until two years of age. The prevalence of stunting peaked at around 40% at approximately two years of age and slowly declined to around 30% by the fifth year of life. The prevalence of underweight was highest (around 35%) in the third year of life and ranged from 25% to 34% during 3 to 5 years of age.”

It added, “Of serious public health concern is that close to one quarter of new-borns are wasted and the prevalence decreases to only about 17% by six months of age. From one to four years of age, the prevalence of wasting stabilizes to about 15% until the end of the under-five period.”

Anaemia and Iron Deficiency

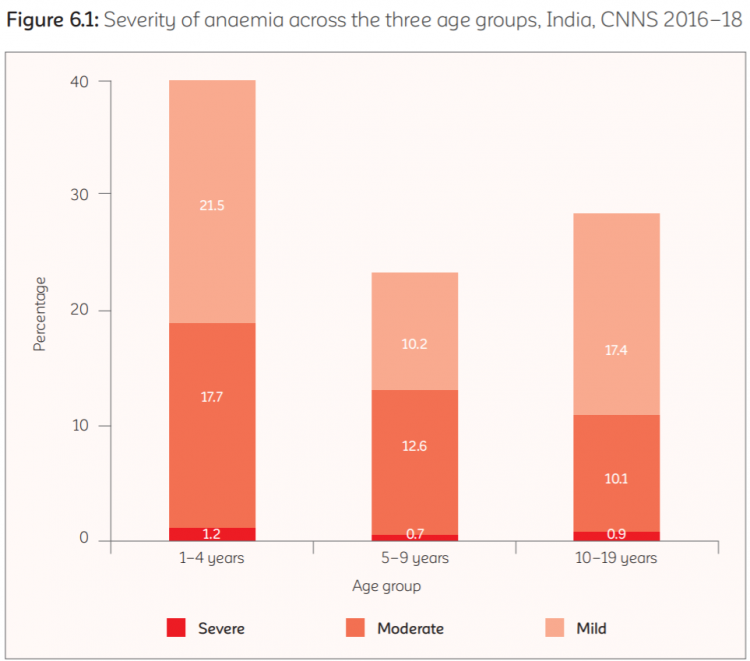

As per CNNS, 41% of pre-schoolers aged 1-4 years, 24% of school-age children aged 5-9 years and 28% of adolescents aged 10-19 years had some degree of anaemia. The severity of anaemia varied across age groups. Among pre-schoolers, 22% had mild anaemia, 18% had moderate anaemia and 1% had severe anaemia. Among school-age children, 10% had mild anaemia, 13% had moderate anaemia, and 1% had severe anaemia. Among adolescents, 17% had mild anaemia, 10% had moderate anaemia and 1% had severe anaemia.

Anaemia was most prevalent (more than 50%) among both boys and girls under two years of age and thereafter, decreased steadily to 11 years of age to about 15%. An increased prevalence was observed among older adolescents. Anaemia was more prevalent among female adolescents 12 years of age and older (around 40%) compared to their male counterparts (around 18%).

The survey pointed out that the prevalence of anaemia varied by the schooling status of children and adolescents. Compared to those currently in school, anaemia prevalence was higher among out of school children aged 5 to 9 years (32% vs. 23%) and adolescents aged 10-19 years (36% vs. 26%). Additionally, the prevalence of anaemia decreased with a higher level of mother’s schooling among both school-age children and adolescents.

It said, “In all three age groups, anaemia was most prevalent among scheduled tribes, followed by scheduled castes. More than half (53%) of pre-schoolers and more than one-third of school-age children and adolescents (38% each) belonging to scheduled tribes were anaemic.”

According to the survey, 32% of pre-schoolers, 17% of school-age children and 22% of adolescents had iron deficiency. It said, “The prevalence of iron deficiency followed a similar pattern to anaemia among both boys and girls, with the highest prevalence among children under two years of age and a steady decline to 10 years of age.”

Among male adolescents, the declining trend in the prevalence of iron deficiency continued with age. However, among female adolescents, the prevalence increased steadily with age due to the start of menstruation. Overall, a gender differential in the prevalence of iron deficiency was observed among adolescents, with girls having almost three times higher prevalence compared to adolescent boys (31% vs. 12%)

It said, “Anaemia continues to be a major public health problem in the country. While iron deficiency is an important cause of anaemia and of concern at certain points in the life cycle (pregnancy, infancy and adolescence), several other factors also contribute to anaemia including deficiencies of vitamin A, folate, vitamin B12 and zinc, illnesses, helminths and parasitic infections. Genetic conditions such as sickle cell anaemia and other haemoglobinopathies are also significant contributors to anaemia in South Asia.”

Also read: India Will Not Meet Nutrition Goals by 2022 at Current Rate, Says Study

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.