Human-Elephant Conflict Escalates to a New High in Odisha as Fodder Shortage Drives Herds Into Villages

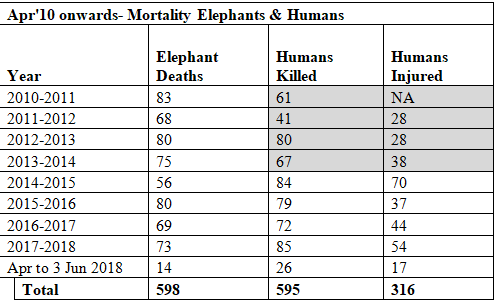

Dhenkanal forest (Odisha): The human-elephant conflict in Odisha and particularly in Dhenkanal has increased to an alarming level, claiming lives of 595 humans and 598 elephants since April 2010, thanks to the rapid dwindling of fodder and drying up of water bodies in the core areas of the state.

Largescale tree felling and the unplanned industrial activities in the forest vicinity have also pushed the elephants to nearby villages in search of food and water causing serious problems for both humans and elephants.

The conflict has become more acute in the recent past since fourteen elephants were killed for various reasons including diseases and train mishaps since April of the current financial year; while 35 human-elephant encounters took place resulting in a loss of the lives of 26 villagers, an all-time high casualty in the state.

This alarming rise in the deaths of both elephants and villagers, as a result of the human-animal conflict in Odisha, has raised a serious concern among environmentalists and wildlife enthusiasts who blame the state Forest Department's ‘non-serious and callous approach’ for the grave problem that villagers in the nearby forests are facing and have sought an immediate action plan to prevent further loss of precious lives.

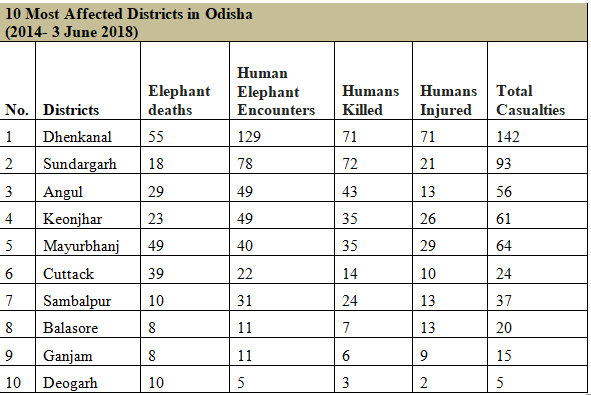

Dhenkanal, with its significant forest cover, has witnessed twelve elephant-human encounters since April in villages like Sogoro, Ichhabatipur, Rodho, Gailo, Pandua, Latadeipur, and Palas Sahi among others, injuring five people and claiming the lives of ten villagers and an elephant.

Since 2014, a total of fifty-five elephants and seventy-one villagers have died, and an equal number of people injured in the one hundred and twenty-nine human-elephant encounters that took place till 3rd June in Dhenkanal itself.

However, not only in Dhenkanal, this human-elephant conflict is witnessed in other districts of the state as well, including Sundergarh, Balasore, Deoghar, Angul, Mayurbhanj, Sambalpur, Ganjam and Cuttack.

According to Biswajit Mohanty, the convenor of Gajah Bandhu, a group of wildlife enthusiasts, “shortage of fodder in the natural forests was the main cause for elephants venturing into human habitations. The shortage happens primarily due to large scale felling of trees for timber, forest fires, rampant harvesting of fruits in summer, cutting off fodder creepers and the forest department’s non-serious approach has brought the situation to this alarming level. The Dhenkanal district is the most affected.”

The correspondent met a 35-year-old lady Sabita Sahoo and her family at Nuasahi, Sogoro village, who was gored by an adult male inside the village early morning on 27th May last year. The injury was so severe that the local Dhenkanal hospital had to immediately forward her to a government hospital in Cuttack. Her condition became so critical at the Cuttack hospital because of the delay, that her family members took no chances and shifted her to one of the leading private hospitals of the state. This saved her life but at a hefty-cost of about Rs 7 Lakh, while they had received a mere Rs 5,000 from the forest department as per their inadequately provisioned guidelines for injuries.

Incidentally a large male elephant had passed through Sogoro village only in the first week of May and villagers were in a constant fear of elephants during the nights.

Thereafter, the correspondent met the family members of late Surendra Naik of Icchabatipur village and late Patali Behera of the adjacent village Radhangi.

A large male elephant, possibly the one that had attacked in Sogoro, had trampled both of them to death within five minutes, early in the morning of 9th June. The male elephant had broken the wall of a temple, entered the premises, and charged at Surendra who was outside his home. After that, while being chased by barking dogs, found Patali at a distance of about 200 meters while she was going to relieve herself.

The villagers said that the particular male elephant had been seen several times in the village after the incident and that they are always-from dusk till dawn- in fear. Both the families have received a compassionate amount of Rs.3 lakhs each, as per guidelines.

In the Gailo village of the Mahabirod Range, a particular Tusker had damaged about eight to ten houses. This happened on the night of 3rd May this year at about 10.30 PM when majority of the villagers barring a few children and women had gone to attend a festival in a nearby village.

From the circumstances it appeared that the villagers had kept liquor in their homes because of which the Tusker went berserk toppling one hut after another, looking for the stuff. Fortunately, not of the children or women were seriously injured. Elephants had entered the same village about two months ago as well.

In Rodho village of the Mahabirod forest range, the correspondent met a 55-year-old man Chakadi Sahu, who was gored in his thigh and genitals by a male elephant. Chakadi was going to his farmland at about 7.30 AM on 21st May, 2017 when it happened.

Incidentally, last month a woman was forced to give birth in a culvert, after her house was destroyed by an elephant herd six months ago in Sarubila village under the Sukruli block in Mayurbhanj district.

A herd of elephants destroyed the house of Pramila Tiria, wife of Manglu Tiria, about six months before. Later, he built a temporary thatched house at the same spot and used to stay there. Unfortunately, even this house was damaged, this time due to the Norwester (Kalabaisakhi) rains.

Without getting assistance from the concerned authorities, pregnant Pramila was staying under a tree in the day time and spent the night in a culvert nearby with her husband and six children.

According to an analysis done by Gajah Bandhu,

- Over 60 per cent of these encounters result in deaths and severe injuries caused by adult male elephants, about half of which happened early in the morning.

- Most of the vulnerable villages face frequent power cuts and have no street lights.

- About 20 per cent of the deaths occurred when people had gone out to relieve themselves.

- About 20 per cent of the deaths occurred when in search of stored grains and liquor, elephants toppled the house walls over the sleeping inmates.

- It is also possible that the elephants, even after attacking the houses for stored food, are still hungry and therefore attack out of frustration.

- The same elephant can attack multiple times in the same day or within one or two days.

- There were two thousand and forty-four elephants in the 1979 census. The number has now reduced to 1976 as per the 2017 census.

According to the data prepared by the Wildlife Society of Odisha, in collaboration with Wildlife Protection Society of India and Elephant Family, nearly fourteen hundred elephants have died since 1990 because of the human-animal conflict, out of which five hundred and ninety-eight have died in the past eight years.

In the same period, twelve hundred people were killed by elephants, with the last eight years accounting for five hundred and ninety-five of them.

From an average mortality rate of thirty-three per year between 1990 and 2000, the number grew to forty-six per year between 2000 and 2010, and reached an alarming average of seventy-three elephants per year from 2010-11 to 2017-18.

If the rising death trend continues, it spells doom for the species as it might significantly overtake the birth rate, Mohanty said.

According to the data, of the five hundred and ninety-three elephants' deaths since 2010, two hundred and seven died due to unnatural reasons such as poaching (95) and electrocution (87), trains killed twenty-three, two died in road accidents and seven elephants died falling into open wells.

“On an average, Odisha is losing eighteen adult breeding male elephants every year. In the last five years, at least sixty-two adult males have been poached, but not a single culprit has been apprehended till now due to the lack of an effective intelligence network”, said Mohanty, accusing the Forest Department of doing little to protect the adult breeding males.

Admitting the need to make a concerted effort to save precious lives, a senior forest official however said that many steps are being undertaken to prevent this human-elephant conflict. “It is an on-going process and the state machinery is alive to the problem. Villagers also have a crucial role to play, like not storing country liquor in their houses which attract elephants to villages.”

Demanding that adult males be radio collared, tracked, and monitored to protect them and also to prevent unsuspecting people from encountering them, Gaja Bandhu, a network of wildlife volunteers, has sought an immediate action plan to curb the high rate of elephant mortality in the state.

Besides the increased number of elephant deaths, Gaja Bandhu volunteers, who are spread across the districts of Sambalpur, Keonjhar, Angul, Dhenkanal, Jajpur, Cuttack, and Deoghar, noted with deep concern, the escalation of human-elephant conflict in the region.

Shortage of fodder in the natural forests is the main reason for elephants venturing into human habitations. The shortage happens primarily due to large-scale felling of trees for timber, forest fires, rampant harvesting of fruits in summer, and cutting off fodder creepers like Siali, said Mohanty, who is also the convener of Gaja Bandhu.

Suggesting both short and longterm measures to reduce human-elephant encounters, Gaja Bandhu has sought preventive measures. Tracking of herds and lone tuskers is essential to anticipate danger to locals. Dedicated trackers need to be engaged at least for the problem tuskers. Regular tracking can also protect adult tuskers from poachers.

Seeking support of the locals, Gajah Bandhu has suggested that tribesmen like Malhars, Mankadias and other forest dwellers are the right candidates for such a task.

Gajah Bandhu also suggestted that power supply to villages should not be cut off when there is elephant movement in the area, presumably to prevent the animals from being electrocuted by sagging power lines.

Communication through SMS/Whatsapp alerts about the position of a herd and lone males has been successfully adopted in Bengal to prevent encounters. Such a system can be studied and immediately introduced in Odisha's elephant districts.

As far as long-term solutions are concerned, Gajah Bandhu suggests that street lights with inverter back-up be installed in vulnerable villages to discourage the entry of elephants and alert locals to their presence at night. Also, air-tight storage bins for paddy should be given to each farmer in the affected areas to avoid elephant raids.

Identified problem tuskers should be radio-collared and RFID listening posts set up in villages which can pick up signals from over five hundred metres. Whenever a male elephant is close by, sirens and lights would switch on to warn the villagers.

According to Gajah Bandhu, the state government's ‘compassionate guidelines’ for loss of crops, cattle and houses, as well as human casualties, etc., are inadequate and ambiguous. Also, the process of payment is extremely unfriendly. Though elephant depredation, loss of property and loss of life have been included in the Odisha Right to Public Services Act, the system of receiving claims and releasing funds is in a dismal shape.

Gajah Bandhu maintains that unfair and inadequate provisions in the rules in case of injuries to humans caused by wild animals need to be amended. Temporary and permanent injuries have not been defined. Secondly, while in the case of temporary injury, the government pays just Rs. 5,000, it is Rs.1 lakh for permanent injury -- but there is nothing in between. Also, the victims are compelled to go to private hospitals in the absence of adequate facilities in government hospitals.

(Arun Kumar Das is an independent senior journalist. He can be contacted at [email protected])

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.