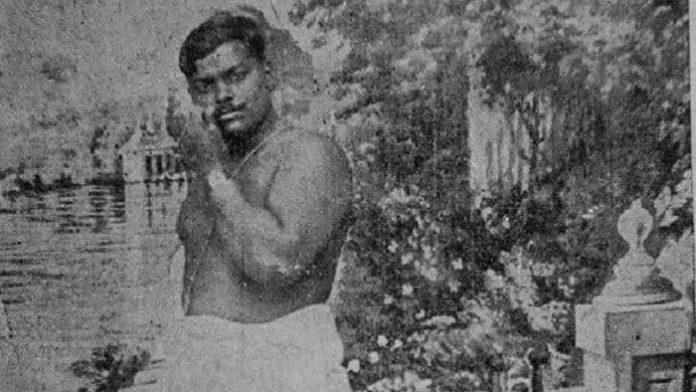

No Mere Martyr: Chandra Shekhar Azad Had No Truck With ‘Kaley Angrez’

It would be a travesty to celebrate the 113th birth anniversary of Chandra Shekhar Azad without considering the significance of his life in the current political context.

Azad was born in an ordinary Brahmin family and his mother Jagrani Devi Tiwari had envisioned for him a future as a Sanskrit scholar. Azad never considered that an option. His short life—he died at 24—is a testament to a raw and unselfconscious lust for freedom that was both personal and imbued the circles he inhabited.

Azad committed himself to fighting the British very early on when he was just 15 years old. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar of over 1,500 peaceful protestors was the primary source of his inspiration to fight the British. It was a cause he shared with his contemporary, the freedom fighter Bhagat Singh.

Azad was Bhagat Singh’s senior by a year. At the time of Jallianwala, the two had not met, but the revolutionary within them was set afire by the massacre. Bhagat Singh picked up a mound of earth from the site and kept it with him as inspiration all his life. Azad did not visit Jallianwala, but he was so moved by it that he decided to dedicate his life to fighting the British Rule.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre prompted Gandhi to launch a non-cooperation movement which went on for two years until February 1922. The legend about Azad is that he had taken a vow in 1919 that he would fight the British and never be captured by them. That is why he adopted the moniker “Azad”, is how the story goes. Perhaps the tale is apocryphal, but it certainly does match the personality of Azad. Indeed, he never could be arrested despite launching numerous attacks on the British.

Ram Prasad Bismil, Rajendra Lahiri, Manmathnath Gupta, Ashfaqulla Khan and Vishnu Sharan Dublish were among the forty who were arrested for the Kakori robbery case. The conspiracy included Azad, who disappeared. He died in 1931, of bullet injuries. Bismil, Thakur Roshan Singh, Rajendra Nath Lahiri and Khan were hanged by the British government, which had been pursuing them in other cases as well.

It is well known that many of these conspirators had Gandhian ideas in the beginning but with time they felt that Gandhi had faltered and let them down. The grouse was that Gandhi had put a lid on the youthful energy smouldering within them. Their disenchantment grew to the extent that in Kanpur they launched a Hindustan Republican Association (HRA) with a written constitution and published manifesto that they called ‘The Revolutionary’. Gupta, Azad and later Bhagat Singh became part of this group. Their bible was ‘Bandhi Jeevan’ by the veteran freedom fighter Sachindra Nath Sanyal.

The HRA constitution did not use the word ‘socialist’ but it was unqualified in saying that its members stood for the oppressed and the deprived. It conceived of a world devoid of ‘exploitation of man by man’. Surely this shows they stood for those on the margins of society.

Azad did not say much. He also did not leave his own writings for the future generations to peruse. Unlike Bhagat Singh, he did not collect books or read voraciously. His vision and worldview come forth in the HRA manifesto, which was vociferously against privatisation and believed in a strong public sector. That is why we should not remember him for his nationalism and martyrdom alone.

In 1928 the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) was launched in New Delhi on September 8 at Feroz Shah Kotla. Azad could not attend the meeting because he could not reach Delhi, but he sent his formal agreement.

In those days Azad and other revolutionaries would collaborate with the Congress party and he met many of its leaders including Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal Nehru and others. The Congress, although it did not agree with their violent political strategies, would provide them with arms and money. Therefore, Azad was the link between the Congress leadership and the revolutionaries.

Azad’s relationship with Bhagat Singh is worthy of note. Most members of his group were afraid of him. Bhagat Singh was very fond of watching movies, while Azad had few hobbies or interests. Azad would keep a watch on their cash while Bhagat Singh would try to whisk away small amounts of it, quietly, to watch a movie. At such times, Bhagat Singh would entreat the others not to tell on him to “Quicksilver”, their name for Azad.

Azad is someone Bhagat Singh looked up to for his bravery, his commitment, for the matter-of-fact way in which he wanted the British Rule overthrown. The two were very different people, but they had come together with a common goal long before they met one another. He was no big reader, approved of their posters, their pamphlets and left his stamp on them. The fact that he associated with Bhagat Singh, who wrote ‘Why I am an Atheist’ and who went to the gallows for fighting for freedom, and remained unwavering in his struggle, says a lot about Azad as well.

Bhagat Singh firmly believed, and said, that 2% of the people cannot rule over 98% of the people. He felt that the majority would have to have a role in governance, not just a small section of people. He opposed exploitation of all kinds. Exploitation by the ‘Kaley Angrez’, or Indian capitalists, after the British had left, was something he opposed oftentimes. This is the worldview that Azad belonged to.

Religion was also not central to either Bhagat Singh or Azad. The former was an atheist, while Azad was a believer whose religion never seeped into his political life. Bismil, Khan and Azad were believers who went to the gallows chanting lines from the Gita or Koran and throughout their lives they worked as one because religion never became a marker of their identity.

I tell people that if you believe in Bhagat Singh, the ultimate nationalist, then why do you need religion to be a nationalist when he did not. These days young people imitate the appearance of Chandra Shekhar Azad or Bhagat Singh, but their imitation is meaningless unless they understand their ideas. We cannot stop people from celebrating Azad whether they comprehend his legacy or not—but martyrdom and nationalism don’t define Azad adequately. His legacy is a set of ideas that go far beyond these two.

S Irfan Habib is a public intellectual who retired as Abdul Kalam Azad chair at the National University for Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA).

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.