Modi Government Shows How Not to Memorialise Partition

Tucked away in the neatly preserved piles of letters of my great grandmother, a freedom fighter who declined political appointments in 1947, was a bunch from her dear friend in Karachi. The letters, written during the tumultuous 1930s and 40s, display a bond between intelligent and sensitive women who, though widowed early, found their metier in the freedom movement—much like the sisterhood between their cities, Bombay and Karachi. Towards the end of 1946, her letters became increasingly grim; the few that came the following year captured the cataclysmic events of Independence and Partition.

In a few, she described the horrors of Partition through stories of people in relief camps in the newly-minted Pakistan, detailing what happened to families they both knew. She expressed disgust at what her community was doing and, as a Muslim, apologised. My great grandmother could never celebrate 15 August in India without melancholy and pain. Her stories of 1947-48 almost always touched on the sub-surface Hindu-Muslim tension or open conflagrations of the Partition when the land was divided and people brutalised, when a mad frenzy made human beings brutal beyond belief. Our Independence was blood-spattered, but we put it all behind us to build a new nation, she would say.

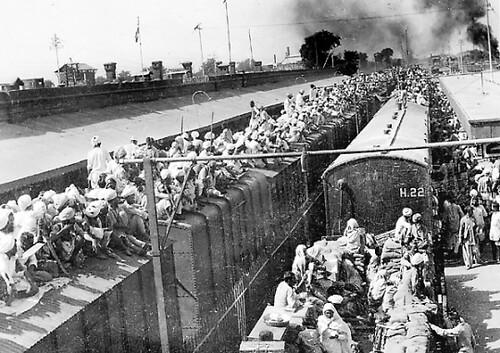

Nearly 12 million displaced, two million dead, thousands of women raped or forcibly abducted and converted by men of religions other than their own, homes abandoned and fields forsaken—the Partition was always a story not fully explored and told. It was like a repulsive scar that must be hidden, a trauma unspoken. Beyond the macro geopolitical stories and leading actors, there always lay human stories of the sort in the letters from my great grandmother’s friend, stories from the ground that speak of both the brutality and humanity in the lives of people caught in the cataclysm.

Shaken by the references to such stories after the 1984 Delhi riots, author-publisher Urvashi Butalia tracked down people of the Partition to write the incredibly powerful “The Other Side of Silence”. Later, Butalia reflected that people were reluctant to remember and chronicle the horror because “there had been, at Partition, no `good’ people and no `bad’ ones; virtually every family had a history of being both victims and aggressors in the violence”.

Bhisham Sahni, whose “Tamas” brought alive that painful era and won him a Sahitya Akademi award, allowed more than 25 years to pass before penning that vignette-like narrative. The Partition Museum in India is a private initiative, as are modest chronicles on social media, all powered by people’s passion for their family’s past rather than a collective memorialisation by a nation. The hurt, real and painful, was recessed in the larger purpose of building a secular and forward-looking country.

It is this hidden hurt that Prime Minister Narendra Modi chose to play on when he declared 14 August would be commemorated as “Partition Horrors Remembrance Day”. Union Home Minister Amit Shah thanked the PM for a “sensitive decision”; his ministry notified it the same day. Both men came to this traumatic issue with their heavily botched record on communal amity, with their perceptions anchored in the ideological organisation which was more comfortable siding with the British—and in Bengal with the Muslim League—than with India’s freedom fighters. What can possibly go wrong?

For a start, it would be instructive to read Modi’s quicksilver announcements against an electoral backdrop. Remember the November 2016 demonetisation decision that analysts said helped in the Uttar Pradesh Assembly election of 2017? The state is poised for its next election. Already a cauldron of religious polarisation, the “Partition Horrors Remembrance Day” helps the divisive agenda.

Modi infused a convenient dog whistle into the innocent-looking idea. Even though he did not mention a community, he picked Pakistan’s Independence Day, thereby conflating the idea of Muslims as brutalisers during Partition. The truth is far more complex, as historians and chroniclers have told us. People of all communities—Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs—were aggressors and victims; neighbours and friends had turned on one another. At the same time, people of all communities also shielded the targeted and helped the victims. There were no straightforward heroes and villains in the Partition saga. But the deliberate though unstated identification of one community with the horrors of Partition allows the faithful bhakt brigade to step up its hate. To a BJP leader, this seems clever; to an Indian, it looks dangerous.

Then, there is the cussedness to mar Pakistan’s big day. There’s no doubt that Partition and later dismembering of Pakistan into Bangladesh shaped India’s attitude and relations with her neighbours. The immediate post-Partition years were tougher than any. Still, India accepted the new reality and went about establishing—or re-establishing—her place in the comity of nations. To now subtly mar Pakistan’s day as “Partition Horrors Remembrance Day” shows more immaturity than newly-divided India’s first government did.

Modi achieved yet another cynical purpose. All of India may be hurt about Partition but none more than Punjab and Bengal, where the suffering lingers in every other home even 75 years later. In Mumbai, south of the Vindhyas, the pain is once removed, given that few families were uprooted or lost all they had. Bombay received refugees, and businesses took a significant hit, but it was unlike the visceral human brutality that northern India, especially Punjab and Bengal, saw up close. With the Union government leading one day to remember its horrors in a pan-India commemoration, complete with its underlying communal slant, the latent and lingering animosity that many Partition-affected people carry can spread far and wide.

Does this mean there should not be memorialisation? Far from it. The mistake of the early decades after Independence was to suppress or hide the horrors of Partition in secret recesses, to focus on the political or meta-narrative without appropriately documenting people’s stories, and to shy away from constructing a memorial to the memory of millions who suffered beyond imagination. Modi made it look like he was correcting the error, but he made a new one. In declaring one day as a “Horrors Remembrance Day”, he reopened old wounds and uncovered scars without offering ways to heal them as a nation. Partition, wrote historian Saaz Aggarwal whose family suffered, was more than rape-murder-looting and involved large-scale migration, loss of ancestral links, loss of food and culture and more.

Modi is priming younger Indians to nurse anger against Pakistan birthed by the “two-nation theory” in selectively recalling the horrors perpetrated by a community. This anger, kept on a slow simmer, can prove electorally useful when Modi’s popular rating sinks and serious governance lapses make anti-incumbency a factor in elections. The day seems less about reaching out to Partition’s victims in the spirit of regret and reconciliation. Instead, it repeatedly tells India’s Hindus, especially the young, that Muslims had dismembered Akhand Bharat.

Cold cynicism and narrow political motives can run a good effort to the ground. It is more likely to happen when the memories and emotions of millions are involved, and a sensitive issue travels across national boundaries, in this case, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Nations that suffer traumatic events find solemn ways to remember them and pay homage to what is lost. The prominent examples are Germany and Israel memorialising the Holocaust and Japan remembering the Hiroshima-Nagasaki horror. The approach is sombre; the intent is to remember the horror so that it is not repeated.

The collective or national memorialisation of Partition is important. More significant is its intent and spirit. If it comes from a place of hate, anger and injustice—as Modi’s idea seems to—it would be better to leave the traumatic memories in people’s homes and personal conversations. They do find ways to express regret, as my great grandmother’s friend did.

The author, a senior Mumbai-based journalist and columnist, writes on politics, cities, media and gender.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.