Linguistics of Blame: Rape Reporting Remains Sensationalist

Image Courtesy: Herald

On Monday, June 10, six of the seven men accused in the 2018 rape and murder of an eight-year-old girl in Kathua were convicted by a special court in Pathankot. The verdict is being seen as the victory of justice over communal propaganda. Last year, the case had garnered international attention, with the media extensively reporting on the story in 24/7. In its reporting of the crime, the Indian media outlets brazenly flouted suggested guidelines on rape reporting by making information about the victim such as her name and images public.

From two rapes per hour in India in 2007 to four rapes per hour now, the statistics on sexual crimes paint a grim picture. Despite this, the State’s impunity and inaction are highlighted in how the Nirbhaya funds remain underutilised till date. Only 42% of the funds have been released since 2015. While India still needs more than 1,000 Special Courts to try cases of rape. The number of reported rape cases has shot up by 88% in the last decade. The depressing statistics indicate that 37 crimes committed against women every hour, meaning that the rate has doubled in the last 10 years.

In such a backdrop, the media coverage however, has fallen into a bandwagon effect. A slew of instances of violence has been reported in the month of May and June, with renewed media attention on the issue of sexual violence against both women and children. In Uttar Pradesh, various instances have come to light. The most recent being the a case of murder of a two year old child in Aligarh, which had sparked controversy, with fake claims of her rape being shared across social media alongside graphic details. It was later discovered in the post mortem report that the child was not raped. Following this, a series of other instances have also been reported from the state. A 12-year-old child belonging to the Dalit community was allegedly raped in Kushinagar, in the first week of May. In another instance, another 12-year-old was also sexually assaulted in a Madarsa in Meerut by a cleric.

A sample from across publications such as Hindustan Times, India Today and The Times of India among other publications was analysed to understand the patterns in reporting. In reports about Kushinagar, the publications were fixated on aspects such as the girl being dragged out of her house and the fact that she was raped in front of her parents. Thereby, attempting to both create graphic imagery for the audiences to illicit shock, while at the same time reinforcing the ideas of shaming the community by assaulting the women of the family in front of her parents.

Given the pervasiveness of rape in India, many stories get subsumed under the bulk of others. To carry them across the water and garner responses from the audiences, media houses often tend to focus on the elements that can incite audiences. This aspect of news coverage has led to the sensationalising of sexual violence, de-contextualising the issue from the larger discourse in the society and misinterpretation of the incident and nature of the crime by taking elements out of context in the news coverage. Often these themes of trivialisation of the victim’s experiences and naturalisation of aggression and violence implicitly condone the crime.

The reports also aim to dehumanise the perpetrator thus creating a vague or ambiguous image around them with language such as “Six men raped the girl” without putting the perpetrator in the spotlight. Perhaps, the most shocking theme prevalent across publications remains to be an attempt to trivialise the discussion on rape and sensationalising the graphic details. In rape cases reported from Rajasthan, the coverage follows a similar pattern.

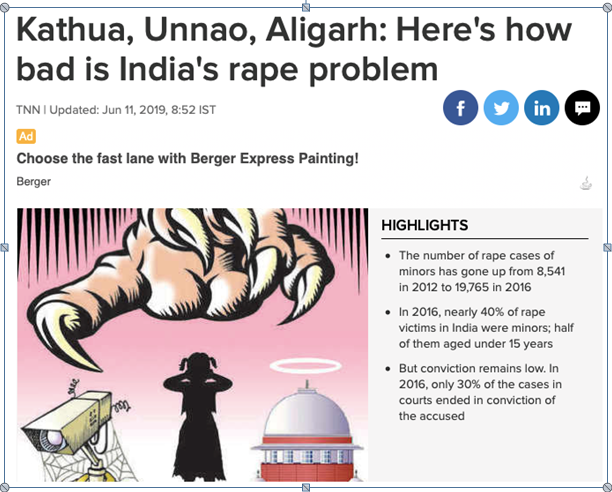

In Alwar, a woman was gangraped by six men in the last week of April and the case surfaced in the media in early May. Lets take a look at the reportage in this case and subsequently in another case in Bikaner. In mainstream media outlets such as India Today and The Times of India, the premise of reports has been centred around the marital statuses of the women involved. The headlines consistently asserted how a “married woman” was raped. In instigating her marital status, the portals implicitly sexualise the accounts, stating that the victim does not fit into the virgin vs. prostitute binary of rape victims. The reporting in the portals has also reinforced the idea of shaming the husband by assaulting the woman as she is the “honour” of the family. The invocation of the victim’s marital status is not limited to media coverage, minister of state in Uttar Pradesh, Upendra Tiwari went on to state that when women who are married and in their thirties are involved in such cases then it is of different nature. His statement points towards the fault lines in how India views its women as sexual objects, after they are married. The Free Press Journal in an article explaining the case termed it a “political slugfest”, thereby trivialising the violence against the victim and associating it with the political connotations of the case. In a similar report, The Indian Express, while discussing the policy actions taken after the case used the term “fall out” to describe the case, essentially calling it a controversy. The harm in disassociating political action by sensationalising the cases is that it absolves the blame from not just the perpetrator but the institutions of power- the government, police and civil society by rendering them invisible in the narrative. Inflicting second wounds on the victims of blame by shaming them actually means that they are being subvertly held complicit in their own ordeal. Trivialisation in media narrative can also be highlighted when media organisations create a generalised framework for reporting on sexual assault such as this story by The Times of India, which clubs all instances of Aligarh, Kathua and Unnao together.

Apart from sensationalising sexual crimes, news reportage through the example of generalisation shown above, trivialises the issue of rape by isolating it from the broader concerns of safety of women and legal action in the reported cases. While reported cases have increased over the last five to six years, conviction rates, unfortunately, have remained stagnant. “At 18.9%, the conviction rate for crimes against women in 2016 was the lowest in since 2007. In 2016, one in four rape cases in India ended in conviction – the lowest since 2012,” IndiaSpend reported. It is important to note that conviction rates refer to only cases which have completed court proceedings in the current year. They do not include cases that carry forward, which incidentally are a large number. At the beginning of 2016, over 1,18,537 cases of rape were pending at the courts. At the end of the year, the pending cases went up to 1,33,813, an increase of 12.5%. It appears that news organisations are primarily interested in focusing on isolated instances of violence and the aspects of the coverage that could yield them benefits instead of shifting the focus to the broader picture of conviction rates.

The Times of India report dated June 11, which clubbed all the cases of Aligarh, Kathua and Unnao

Imagery of Sexual Crime

Not just text, the imagery used in the media reports has led the audiences into visualising the crime, giving graphic details, meant to horrify the readers, while cringe worthy details of the crime are shared to elicit shock, limiting the discussion on the issue of the crime. The portrayal is problematic not primarily because of the titillating account it creates but because it narrows down the discussion on rape and power. This leads to the account becoming massively sexualised, the intention behind sharing these details in the first place to encourage sales by dehumanising the victim and reducing her identity to that of victim. While publishing an analysis on the case of an eight-year-old’s rape in Bhopal, India Today shared a graphic image as its thumbnail. The use of such images subtly build a narrative in one’s mind about the helplessness of the woman and the superiority of the man shedding light on the larger power dynamic in the case. Images try to recreate the scene, or show a distraught woman whose world has seemingly fallen apart, or use colours like red and black that suggest blood and something sinister.

Image caption: The India Today report which used a graphic image as its thumbnail.

Imagery showing voyeurism or loss of innocence has been seen more commonly in the cases involving violence against children.

Image caption: A voyeuristic image used by the India Today.

If it wasn’t for these elements the story would have met the same fate as the other bulk of stories do. From a consumerist perspective, these accounts border on the line of crypto-pornography. The reportage analysed above can easily qualify as hyper-exploitative journalism, where details of the victim are used not to evoke compassion or understanding but to sensationalise the issue.

Amidst this, it becomes important for news organisations to introspect on whether or not they are following the set standards on the reporting of sexual harassment and violence against women and children

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.