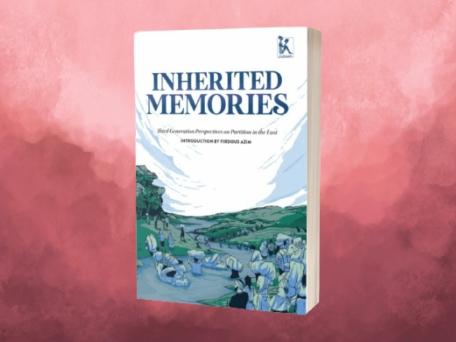

Inherited Memories: Third Generation Perspectives on Partition in the East

In 2015 the Goethe-Instituts in Kolkata (India) and Dhaka (Bangladesh) began a collaborative project entitled ‘Inherited Memories’. The project began with a key question that grew out of discussions on memory and history: was there such a thing as a ‘culture of remembrance’ in India, something akin to the Erinnerungskultur in Germany? The question was asked specifically in relation to the Partition of India in 1947: why was it that such a major historical event found little reflection in public memory? At the time these discussions began, many, perhaps most, of the survivors of the 1947 Partition were no longer alive and their memories therefore lost to us. It is often said that memory jumps a generation, so a decision was taken to talk across borders with the children and grandchildren of Partition refugees in the Bengal region, to look at how memory is passed down, what is retained or lost, and how it is owned and shared by subsequent generations.

This book, which comprises interviews from both Bangladesh and West Bengal, is the result of these discussions. Guided by a committed and engaged group of writers from both countries, the book explores, through the stories of ancestors the memories people carried with them, the things they never forgot, the yearnings that did not go away, the journeys that remained unfinished, and those that were accomplished. Through these, it examines how history simultaneously looks so similar and so different from either side. Introduction by Firdous Azim.

Foreword

Nasez Afroz

As the issues of migration and refugees due to the escalation of conflict in Syria raged on in world politics, particularly in Europe, it was just the right time to carry out research on memories of one of the biggest refugee crises and migrations in recent history. The current debates mostly centre around the broader theme of what impact the refugees would have if they were allowed to settle in a particular society. So, it would be pertinent to look at what legacies previous massive conflicts, and the mass movements arising out of them, leave in the societies these refugees moved into.

One such event is the Partition of the Indian subcontinent and the creation of India and Pakistan in 1947. A considerable amount of research has been done on the Partition of India and its impact in both the east and the west. Some oral histories have also been, and are still being, carried out to record the testimonies of witnesses of Partition, and they have either been published or made available on the internet. But there has been hardly any research on the post-Partition third generation. And there is little doubt that the third generation would have grown up with memories inherited from the two generations that preceded them, memories that are partly idealised, party imagined and partly extremely negative. This process of passing on and inheriting memories is likely to distort the contours of an individual’s understanding of history unless divergent views are brought together and presented in parallel.

Keeping these in mind, the ‘Inherited Memories’ project was conceived to explore how these ‘un-objectifiable memories’ and subjectively transmitted stories influence the third generation’s understanding of post-partition history.

[…..]

The Search for Roots

Tunazzina Sharin

It was the month of August in the year 1946. Communal riots were spreading fast in the streets of Kolkata. Like many others, a girl of about six was trying to save her life by fleeing with her family and other Muslim neighbours from the neighbourhood of Ramchand Ghosh Lane in the Beadon Street area of North Kolkata.

She might have forgotten a lot about that day, but the way they had to walk barefoot in the scorching summer heat and on the burning tarmac of the lanes of Kolkata still remains strongly etched in her memory.

Seventy years have passed since then. The six-year-old girl is now 76 years old. It is yet another month of August and the year is 2016.

She gets out of a car at the same old Beadon Street, near the gate of the historic Minerva Theatre, in order to trace her long-lost home at 7 and 8 Ramchand Ghosh Lane, which she had left behind in her childhood. The crew behind the lens started preparing to record her first emotions with their cameras.

My mother and I were a part of the search for this 76-year-old woman’s home, this woman who was my grandmother. One of the lanes that we crossed on our way from Minerva Theatre to Ramchand Ghosh Lane was named after Zarif, a forefather of my grandmother. Interestingly, it seemed that the architecture of the North Kolkata houses had not changed much, and it felt like they stood almost in the same fashion as they used to some 70 years back.

House number 8, which used to be the main ancestral home of my grandmother, stood in a dilapidated condition, urgently needing renovation. Jointly owned by many families, rooms have now been added to the original structure to accommodate more people. The way through the main door was exceptionally dark and slippery. Grandmother had told us about a square shaped yard in front of the house with two platforms on either side. This used to be a favourite spot for the family to have their morning and evening chitchats. This yard has now been transformed into a room, perhaps to meet the growing demands of the increasing population of the present household.

The quadrangular courtyard also seemed to have reduced to almost one third of what it used to be, because of the rooms that have now been added. As we went up the very dark and dingy stairs we were cautioned against falling down by one of the residents, as the slippery stairs could very well deceive newcomers who were not very accustomed to them. We were guided up to the roof terrace by this person, who had to get the keys from another woman in the building.

As we went up I could not help but feel sad at the crumbling condition of the unkempt terrace. The two rooms in the terrace, however, looked quite similar to what they used to be during my grandmother’s time there. One of them has been turned into a home for pet birds owned by one of the tenants, while the other remains locked and unused.

There were a few broken utensils on one side of the terrace, a few clay tubs with flowers scattered here and there. A dalim or pomegranate tree was placed on one of the walls; it seemed like a bonsai variety to me. One could easily see quite far into the distance from the terrace. As I stood there, it felt strange to think that this was the very terrace from which the men of the family had to fire guns at the rioters from other localities during the very riots in which my grandmother had to leave her home.

After a series of photo shoots on the terrace, we went down, precariously following the same staircase.

It was when we were coming out that I managed to catch a final glimpse of the house. The half opened electric box, cement flakes coming off the damp walls, its unkempt, unrepaired state all added up to a sorrowful picture of the dilapidated structure as it stood silently loaded with memories of the past.

We made our way out of the house with heavy hearts, as the August sun blazed over us. Pausing for a while to interact with a small child in his mother’s lap, we walked towards a curious looking teashop at the end of the lane, with a mosque-like dome on it. Intrigued by the peculiarity of the structure, we entered the shop, ordered a few glasses of tea and asked the woman there about the history of the building. She responded by recounting a story she had once heard from her father-in-law. She narrated it to us excitedly, telling us how the then owner of this house, probably an Imam, had given the keys of this building to her father-in-law at the time of the riots, and asked him to save his house from becoming a drinking den as he had to flee from the locality to save his life. From then till the present day, the building had always been taken care of as promised by her family, she added.

After finishing our tea, we moved out to the main road, leaving behind my grandmother’s ancestral home, the mosque turned teashop and the narrow lanes of north Kolkata with their roadside water taps relentlessly gushing out water. My search had finally come to an end. As we left Beadon Street I realized that this was probably my first and last meeting with the old decaying house at Ramchand Ghosh Lane, which was standing still and getting old, and witnessing history unfold in front of it every day.

[….]

The Bangaal-Ghoti Divide

Sraboni Ghosh

Nobody takes these things seriously anymore. I don’t think so. Why? Because I’ve been born in this country and this to me is my native land. But there is of course this thing about one’s roots. I really used to feel quite despondent, especially after seeing what we had there. I had seen our village, and the land that was ours. It was a large tract. So, deep down, one does feel sad. And when all those people were telling me about my grandfather and father, I felt so pensive, and this question welled up in me – why did we have to leave all this and move away? It would have been so much better had we remained there. Apart from this, considering our present condition, there is no question of going back. I don’t think of it.

What significance does [the border] hold for me? It would’ve been better had it not been there at all, because a line or border cannot create a cleft in the minds of people. I’ve seen my father and mother – though they live here physically, a part of their heart and mind remains in their native land. It is almost as if a part of them has been left there. I feel it is better done away with. If there wasn’t any border or so many fences all around, we could have gone there so often, and our relatives there could have come here too. It would have been so convenient; we could’ve touched our land.

All borders. That’s what I feel. What use are borders anyway? I don’t understand. What’s the use of creating enmity between people? There’s no use, is there? There’s all this tension along the border between India and Pakistan. There’s so much acrimony. It would have been best if the border had not been there at all. After all, they lived together as one people, didn’t they? A country got partitioned? What for? Why? Maybe it was a consequence of certain political circumstances, but did the people actually want [Partition] at all? Perhaps they don’t want borders segregating them, or perhaps they don’t even understand what constitutes a border. When I visited my native place in Bangladesh, everyone, from the autorickshaw puller to the rickshaw puller was so cordial, so friendly, asking me, ‘Oh! So you lived here once? Where did you live? Where was your native village?’

The warmth with which they would strike up a conversation – there was such familiarity and a genuine fellow feeling in these exchanges. It makes you feel like ordinary people don’t really understand the significance of a ‘border’. To them, being a Bengali is what matters. It is immaterial whether you are Hindu or Muslim. You are a Bengali [regardless]. You’ll see how two Bengalis bond when they are abroad. It doesn’t matter whether you’re from India or Bangladesh. I’ve felt so elated whenever I’ve seen a Bengali on my travels. It hardly weighs on my mind what that person’s nationality is or, for that matter, what their religious beliefs are.

India [is my native land], of course, [but it’s different for my parents]. You see, my parents were born there, so it is natural that they would have a different kind of attachment to that country. They were brought to a new land. If you uproot a tree and transplant it somewhere else, even with all the care in the world, its roots remain in its place of origin. I do feel sad, I do feel despondent about our coming away, and there is always this feeling that it would have been so good had I been able to go there. But the fact remains that I was born here; everything I have is here; I’m a girl of this soil. Let me give you a small example. Before you get married, the attachment to your father’s home is supreme; but once you get married, there is also a pull towards your in-laws. You cannot deny either, and both are equally strong. I feel, in the case of my parents, they cannot deny this dual pull. In my case, I simply cannot deny that this is my country.

Sharing Stories

Everything – I want to tell the next generation everything because I want subsequent generations to know what it was like – a whole generation of people, their families who lived in a particular time, who had their roots in a particular country, who had to leave their own country – the struggles they went through and how they overcame adverse circumstances to establish themselves once again. My father and his elder brother had to undergo such privation. They had to keep the household running even as they tried to study. They had to take up so many odd jobs just to eke out a living somehow. It is essential that the next generation also knows the stories of these struggles. So, I want to tell them everything in detail.

I told you some time ago how [my father and uncles] would buy goods from the farmers directly and then sell them at a profit at the weekly haat. They would buy rice and other things too. They would do this very quietly, and my grandmother didn’t know about it. She was a very grave and strict lady. She didn’t know all this was going on. In my memory, too, my grandmother has that grave [feel to her]. When my father and his siblings grew older they started a small business, then bought an autorickshaw. We also had a biri shop which worked like a biri manufacturing unit. Then there was the garment shop, which we still own. That’s how they established themselves. My mejo-jyethu got a job. So this endeavour to pitch in, to make the family’s economic situation better, was always there.

I visited Dhaka when I was in Class VIII. That was in 1998-99. I saw this canal flowing past our village homestead, verdant all around, and the house was like any other village house. But here in Kolkata our house in Beleghata was built on a very small patch of land with bricks and mortar. No such expanse of greenery, but you know wherever Bangaals live, they try to make the surroundings as green as possible. But our Jalpaiguri house is very different. Lots of trees are planted there. My jyethu is in the habit of planting trees – something that I’ve inherited – and he has planted lots of coconut and betelnut trees all around our house in Jalpaiguri. Maybe he’s trying to recreate our village homestead because he misses his home.

[My family] had to live in rented lodgings at first. Then this plot was purchased in the name of my pishi-thakuma, a child widow, to provide for her. Grandfather bought the land in his daughter’s name. My grandfather, my father and my jyethu lived there. Obviously, the living conditions weren’t ideal, and it wasn’t to their liking either.

But when we went to Jalpaiguri – and I told you about the Sahas (owners of a nursery) who helped a lot – we bought a house right beside theirs. Our house there is quite a large house, and as our financial situation improved, the area was enhanced, more land was purchased. I feel it was impossible for them to continue living in a small, constricted space; the aspiration for a larger holding remained. That’s my assessment. I’ve never asked Father what he felt about it though.

During Partition, the situation was tremendously volatile; there were riots. That’s why [my grandfather] came away. Then the situation on both sides became calmer. The house in our native village remained, and so did the people who were looking after it, so he had to go back. Besides, my grandmother was there too. My grandfather continued to travel between the two countries. My great-grandfather, as I told you earlier, had this rented place, from where he would keep the operations going both here and in Bangladesh. My grandmother would see to the affairs there, and my grandfather would be on the lookout for income opportunities on his visits here. But this was rendered impossible after 1971. Perhaps my grandfather felt that it would not be possible to live there after that. Father was a child, only two or three years old. He remembers nothing of those times. He just remembers that they had come away. Father used to be very naughty as a child. My grandma would try to scare him by saying, ‘Let your father come here from that country, then you’ll know what’s what.’

Father was brought [to India] in 1952. He remembers sitting for a scholarship test when he was in Class IV, around 1955 or 1956. That he remembers, but he cannot remember the years before that very clearly. Those recollections are somewhat hazy. I’ve heard these stories from my father, so I too wouldn’t be able to tell you about those years.

[As I told you earlier] grandma had a tremendously powerful personality and had a lot of grit. She knew how to live alone and managed pretty well. There were many people who tried to scare her into giving up her house and going away, but she managed to ward off these threats. I’ve heard stories about how people would dress up as ghosts and try to scare her at night, and how, unperturbed, she could come out with a kathari in hand to catch the truant prankster. So she never really had any trouble. And, as I told you, there were helpful neighbours like Gobindo kaku and the Muslim families, who were very supportive. But after 1971, I guess they too couldn’t assure her safety, because the Rajakars were pillaging and murdering Hindus and Muslims indiscriminately. So it was no longer possible to remain there. They had to come away. […] Apart from the little bit of a chase that my grandfather had to dodge, the coming away was pretty smooth.

[In our home] it was my grandma alone who was an adult; all her daughters were still kids. Two of my aunts were really small, so I don’t know whether they had to face any struggle at all. They used to help a lot with the daily household chores, but I don’t think they had to go looking for jobs or sacrifice their education. That much is certain. Coming away from an established household – what I mean is, the family had a handsome income in Bangladesh. There was a lot of agricultural land where paddy was grown. When they came away, that wasn’t there any longer, so obviously there was financial trouble.

As I told you, I’d like to share everything with them. […] I strongly feel that people must know their past, because if they don’t, they’ll never be able to know their roots. Hence, I would like to share these memories in their totality. In fact, there are no harsh memories that I would like to hide, or not want to share. Most of these memories are rather funny – grandma standing up to the pranksters, or grandpa starting his medical practice. I also want to share stories of how my father and his brothers struggled to keep their education going. I want to share all of this with them. Or my mother’s story, for instance. She lived away from her parents, with her paternal uncles. Her memory of being homesick – just imagine a small child, studying in Class III, wouldn’t it be natural for her to want to be close to her own parents? She missed her mother a lot. These are the things I want the next generation to know.

[My parents’] memories have something in common – this longing for a place left behind. Mother had this pain of staying away from her family, whereas father had memories of struggle with his family beside him. Just a little different perhaps; but in both their memories, there’s a lot of pain. The pain of Partition – this pain gets so entrenched in the memory of a child that it never goes away, come what may; people carry it with them like a burden.

This is an excerpt from Inherited Memories: Third Generation Perspectives on Partition in the East published by Zubaan Books. Republished here with permission from the publisher.

Firdous Azim is a professor of Literature in the Department of English and Humanities at Brac University. She is also a member of Naripokkho, a leading feminist organization in Bangladesh. Her works include The Colonial Rise of the Novel (1993), a special edited volume (with Nivedita Menon and Dina Siddiqui) of Feminist Review, ‘Negotiating New Terrains: South Asian Feminisms’ (2009), and a special issue of Inter-Asia Cultural Studies entitled ‘Islam Culture and Women’ (2011).

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.