Ground Down by Hardship, Farmers Ready for Historic Bandh on Sept 27

Representational Image. Image Courtesy: PTI

A recently published government survey report has once again shown that farming in India has become highly unprofitable, with monthly income from crop production estimated at an average of only Rs 3221 in the country. Farmers in 16 states earn even less than this average. This has forced most farmers, especially the small and marginal ones, to supplement their incomes by doing wage labour or small non-farm work. Another aspect is the abyss of debt in which farmers have sunk – the report reveals that more than half of India's farmers are deeply indebted.

In these dire conditions, the Narendra Modi-led government's obstinacy in pushing through a set of laws that will further reduce incomes and force the farmers into servitude of corporate houses has naturally led to widespread opposition. Farmers have joined with workers and employees to confront the government with what amounts to alternative policies. It is in this series of struggles and strikes that a powerful combination of over 400 farmers' organisations and ten central trade unions have called for a 'Bharat Bandh' or general strike on September 27.

HOW MUCH DOES A FARMER EARN?

In the past year, as the farmers fought repression and braved harsh summer and winter to continue their fight for the withdrawal of the 'Black Farm Laws', government or ruling party leaders and apologist intellectuals have tried to show that farmers are apparently not doing as badly as made out, and that its only some vested interests that are propping up their struggle.

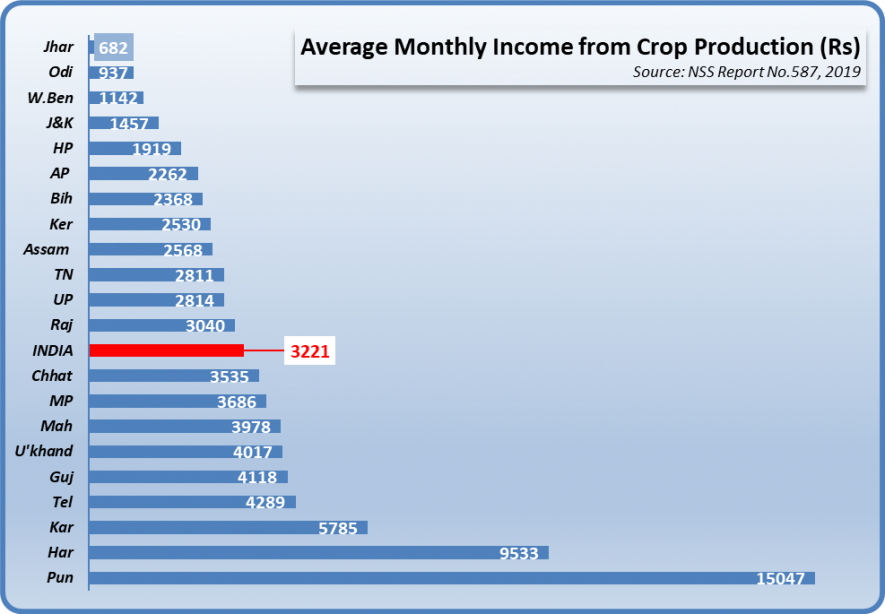

A report by the National Statistics Office (NSO) under the central government destroys this myth. In a survey carried out in 2018-19, the profits or earnings of farmers from crop production in various states were found to be abysmal, as shown in the chart below.

Seven smaller North-Eastern states and Union Territories are not included in the chart for the sake of clarity. Only Punjab and, to some extent, Haryana reported farmers' incomes that would qualify as minimum wage levels. The rest of the states had subsistence-level earnings, with some of the poorest states like Jharkhand, Odisha Bihar, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and others barely reaching Rs 3000 per month.

These are average monthly incomes, computed by subtracting the expenditure on crop production from the total receipts. Expenditure includes paid out spending (like seeds, fertiliser, labour, etc.) as well as imputed spending (like family labour, interest on loans etc.). Since these are annual averages, they cover all crop cycles that farmers undertake.

A notable feature is that the incomes vary sharply depending on how much land the farmer is tilling. Over 83% of farmers are small and marginal, that is, they operate landholdings that are less than two hectares, with over 70% having less than one hectare. Their incomes are much less than those who have larger landholdings. The averages are, as always, hiding a much deeper level of deprivation.

It needs to be emphasised that even in Punjab and Haryana, income levels are very low although they are much higher than in poorer states. Thus, about Rs 15,000 per month in Punjab or Rs 10,000 in Haryana is equivalent to minimum wage levels for unskilled industrial workers or informal sector workers in these states. The government's own Seventh Pay Commission had recommended back in 2016that its lowest-paid employee should get a minimum of Rs 18,000 per month.

This is why farmers are demanding better remunerative prices for their produce, which means that the government needs to fix a support price that should give them a decent profit after meeting all expenses. Such a formula was recommended by MS Swaminathan led Farmers Commission way back in 2004, but it has not been strictly implemented yet.

SO, HOW ARE FARMERS MANAGING THEN?

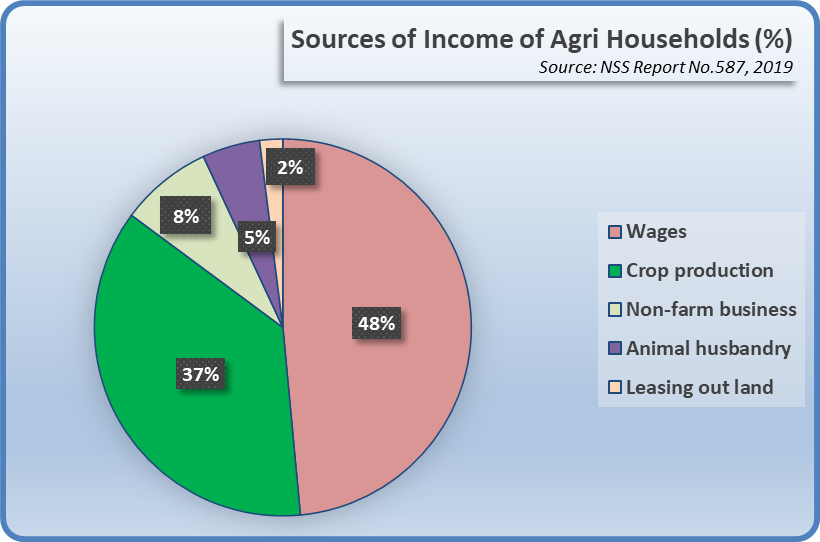

The obvious question that arises then is – how are farmers in India managing with these meagre earnings? The NSS report answers this question as well – families are supplementing their farming incomes with other work to make ends meet.

On average, for the country, a household that depends on agriculture is actually deriving only 37% of its income from crop production or cultivation, as shown in the chart below. The bulk of its income – 48% in all – is derived from wage work. This involves working in other people's fields for wages.

About 5% of income comes from farming animals and 8% from doing some non-farm business like retail shops etc.

What this shows is a system that is tottering on its last legs. Since there is rampant joblessness, there is not much scope for getting substantial income from non-farm work like jobs in industrial or services sectors. This forces more and more people to work in agriculture for less and less income. It's a downward spiral into poverty and misery.

GROWING INDEBTEDNESS

Since it is impossible to carry out routine agricultural activities with this kind of income, farmers are forced to rely on loans to survive. The NSS Report also lays bare this part of the story: just over 50% of farmers are currently indebted, and the average debt is a whopping Rs 74,121 per household. As always, these averages hide a much more serious picture. For instance, in the so-called more prosperous agrarian states like Punjab and Haryana, the average outstanding loan taken by each agri household is Rs 2 lakh and Rs 1.8 lakh. Other states with high average debt per farmer household are Tamil Nadu (Rs 1 lakh), Rajasthan (Rs 1.13 lakh), Karnataka (Rs 1.26 lakh) and Kerala (Rs 2.4 lakh).

Similarly, certain states have very high indebtedness prevalence: Andhra Pradesh has 93% farmers indebted, Telangana has nearly 92%, Karnataka has 68% and Tamil Nadu has 65%. This, incidentally, blows the lid off the popular myth that farmers are in crisis only in some states, and the farmers' movement is only confined to those. In reality, farmers are in distress everywhere in the country.

NEW FARM LAWS WILL BE A DEATH BLOW

The Modi government sought to 'resolve' this crisis by handing over the whole farming sector to corporate entities, both domestic and foreign. The new laws will pave the way for private business houses to determine what the farmers will sow, where they will sell their produce, at what price it will be bought, how much will be stocked or exported by traders, and even the prices these businesses will charge from consumers. There will be no guarantee of a minimum support price. In fact, there will be no guarantee of government procurement, implying that the ration card system will go out of the window. In sum, it is a catastrophic policy that will push the large mass of common people into poverty and debt.

The farmers have seen through this policy, and hence they have been fighting for its scrapping. In this fight, they have been joined by other powerful forces – the industrial working class and a large number of employees from the service sector. These two sections are facing a similar challenge because the Modi government scrapped earlier labour laws and introduced hire and fire rights for employers, diluted wage fixation procedures and presented difficulties in unionisation, among other things.

The Bharat Bandh of September 27 is thus a historic action meant to protect the country's working people from impending slavery to corporate houses.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.