A Feminist’s Rattle: Gender Politics of Rent

Image Courtesy: Facebook

“Rattety, rattety

Sounding the rattle,

they ratted on bailiffs

Rata-tat-tat

intent on evictions”

- excerpt from Mary Barbour’s Rattle by Christine Finn

A quick search on the internet of the above will bring you to the massive rent strike of 1915 in Glasgow led by Mary Barbour along with around more than 25,000 women tenants. The women sat with bells and rattles ringing them at the threat of eviction alarming others to come to their rescue. The hike in rents were seen as an act of exploitation by the landlords seeking advantage of the war situation. With men off to fight, the women had to face the brunt of harassment and eviction threats, leading them to organise themselves and rattle. Rent strikes have been of particular interest to the working class, specifically, women.

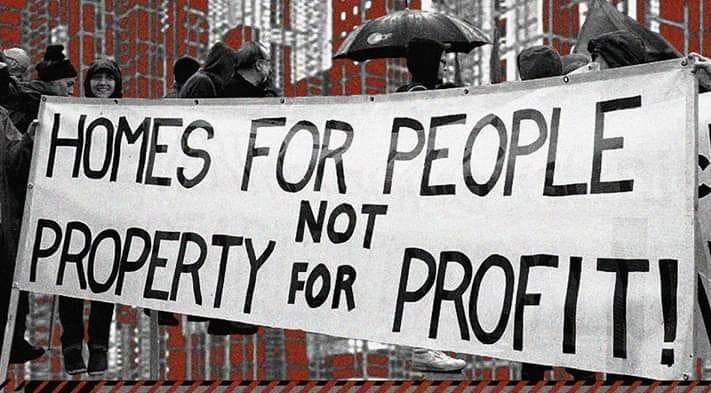

While it is not a completely new phenomena, the need for a rent strike seems to be echoing right now. You wouldn’t hear the rattle during a pandemic that requires you to ‘stay home’ but the sound of “can’t pay, won’t pay” rings loud around the world on windows, doors and social media. Rent strikes are already being proposed in the U.S., U.K., Australia and even in Indian cities like Mumbai and Delhi.

Within this whole discourse of rent strikes and tenant unions, the gender politics of tenants is, more often than not, overlooked. For us to come to a holistic understanding on the need for tenant unions, it becomes imperative that we look at ‘women as tenants’ as the specificities that such a grouping allows and holds the power to unearth questions of inequalities, discrimination, harassment and the like in a much more vivid fashion. No doubt, tenant unions are crucial ubiquitously to many sections of the society. However, the cognisance of intersectionality promises a better understanding in the realisation of the pivotal role such a union can play.

There exists vast literature on the gender wage gap but the fact that it results in a gender rent gap, i.e. women spending higher proportions of what they earn on their rent is often overlooked. This makes being able to afford a decent place (forget living alone) a luxury, often leading them to share spaces in cheaper localities. This exposes them to other vulnerabilities like spending more on commuting and transport, lack of privacy, restriction on movement and mobility around the city, etc. Moreover, women often are charged more in the name of safety and security. In simple terms, accommodation is a relatively costlier affair and securing a place in a decent safe locality is harder for some just because of their gender. In Indian cities, these disparities are glaring. In Delhi especially, the discriminatory patterns of rent and fee have been pointed out by students on multiple occasions and have been protested against from time to time.

Owing to the patriarchal structure of most Indian households, women sent to other cities, especially Delhi, for higher education are often not supported throughout. Often when the families’ resources are limited, a woman’s education ceases to be a priority. Since the women are to be married off and owing to the patrilocal patterns of residence Indians follow, the investments in terms of her academics will only bear fruit to the in-laws. The appearance of a potential spouse, the need to lend a helping hand to earn for the family, etc., are other reasons which lead to families calling back the women, disrupting their studies. In attempts to control their own lives, evade marital pressures from the family and pursue academics, many women work part-time striving to be financially independent and funding their own education. This makes it all the more difficult for women to continue living in cities during this pandemic induced lockdown. With no source of income or family support, such women are often left alone to source their own rent.

Family and societal pressures on women to lead their lives in a certain way and to follow the cultural norms and gender roles, often restrict many opportunities for women. The media-accentuated image of cities like Delhi being the capital city of rape intensifies the fear of sexual harassment, often making women pay more to secure a safe accommodation, snowballing mental stress on their families. Especially during this lockdown when most students are back home, many women are having to live alone at rented places or in deserted hostels and PGs, making them more vulnerable to harassment of all kinds from houseowners and other authorities. The houseowners and hostel and PG wardens are very well aware of the fact that these women have nowhere to go and monstrously take advantage of their helpless situation by threatening them with eviction, increasing rents, etc., often entering their houses and rooms without permission. Parents send their children to study in far off cities assuming hostels are a safe haven but many a time, these safe havens themselves become a source of threats and harassment.

The societal ‘honour’ attached to a woman often leads to moral policing of behaviour and lifestyles, resulting in discriminatory practices in terms of accommodation and bullying from the houseowners. For instance, female students from the North Eastern states of the country living in Delhi reported that it becomes very difficult for them to secure a place because of the stereotypes attached to them of being promiscuous which results in them having to pay more than usual. They are often made passes at by the landlords (Duncan McDuie-Ra, 2013). Female students living on rent are also frequently bullied if they have male visitors and are judged on the basis of the time they return home, the kind of clothes they wear, their lifestyles, etc. “Our owner called us up randomly, asking us to vacate the house because apparently, our neighbours complained that a lot of men visit our house,” a student pursuing her masters from the University of Delhi and residing in Kalyan Vihar said. On another instance, “We were forced to vacate a house after paying the security because the owners suddenly decided that men would not be allowed in the house. We study in co-educational colleges, naturally making the visits of our male friends a common practice. Moreover, we have group projects which makes it inevitable for our male colleagues to drop by too. So, we decided to leave the place, and the landlord and the broker harassed us, making up stories just to hang on to our security amount. We eventually had to let go of the money, the price we had to pay in exchange for peace from the bullying,” another student from DU residing in Vijay Nagar said.

These female students are not alone in their experience. Women are often spoken to in higher tones, intimidated, and taken advantage of by houseowners and brokers. The houseowners and brokers often have strong networks in place and the police seem to be hardly helpful to the tenants in such contexts.

The pandemic induced lockdown has not only intensified the already existing problems for women but has also created new ones. The increasing number of eviction threats, the intensified bullying and the harassment by houseowners, and hostel and PG authorities, have amplified the precarious living conditions for women. With no structure in place to seek help in such situations, the recently started Student Tenants Union in Delhi by members of the Students’ Federation of India came as a support space and as a sigh of relief to many tenants, especially women. The number of cases received by the union on their helpline on a daily basis is evidence for this fact. Though the plight of female students in specific has to be highlighted and addressed at a much larger level, this union is a start nevertheless. The union’s demand for a rent waiver for the period of lockdown seems to be pivotal for women and their precarity, now more than ever. We might not be able to hear Mary Barbour’s rattle amid the national lockdown, but our voices can definitely be heard loud and clear.

Just like with any other social issue, the lockdown has shed light on the plight of tenants and the need to collectivise. Not limiting it to the lockdown, the tenant union, like any other union, has the scope to hold one end of the bargaining power, eliminate the middle-men, find recourse to discriminatory practices on the basis of religion, region, ethnicity, caste, sexuality, etc., protect one from harassment of all kinds, and raise collective demands. With proper legal measures, this, hopefully, will be able to cement itself with time.

Also read: Maha Postpones Rent Collection; Case Doubling Rate Stands at 6.2 Days in India

The author is a student of Sociology at the Delhi School of Economics and a student activist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.