Shahnama Revisited: Iran’s Turbulent Journey to this Moment

In Iran’s turbulent and troubled days her people have looked back to their past for inspiration. The nostalgia was initiated in the 11th century by Iran’s greatest poet Firdausi in his famous Shahnama which is one of the greatest national epics in world literature. The epic celebrated ancient Iran’s heroes and history and reflected the fact that Islam was originally alien to the classical heritage of Iran.

Firdausi laments:

Oh Iran! Where are all those kings

Who adorned you

With justice, equity and munificence/

Who decorated you

With pomp and splendour?

Iran’s history, like India’s, is woven with legends and facts and goes back three millennia BCE. Firdausi celebrated the ancient powerful Achaemenid dynasty whose kings Cyrus, Darius and Xerxes expanded their empire beyond Fars (Persia) to encompass Afghanistan, Central Asia, Southeastern Mediterranean and finally Greece. Darius’ army seized Athens and set fire to the Acropolis. In turn Alexander of Macedon defeated the Persians and extended Greek rule to former Iranian territories that became the Seleucid Empire. Iran’s classical heritage lived on through Ghaznavid and Mongol invasions.

Iran continued as a world power under her Sassanian rulers who built their capital at Ctesiphon. In the midst of this effulgence the Umayyad Caliphate at Baghdad defeated Iran’s Shah Yazdegerd III in 655 AD. However, Islam was not able to extinguish classical Iranian culture; the new rulers absorbed and adopted Persian ways, especially the art of governance. But the conflict between Iran’s classical legacy and Islamic traditions continued into the present. Several dynasties ruled Iran with varying effects. It was under the Safavid dynasty that Iran experienced another burst of glory, especially under Shah Abbas the Great in the 16th century. This effulgent era was followed by the rule of the Afsharid, and then the Qajar dynasties. By the nineteenth century Iran fell into chaos, poverty and weakness.

Nations have turning points in their existence, when their destinies are decided. A grim turning point in Iranian history was in 1908 when a British geologist George Reynolds under the patronage of William Darcy discovered oil. The Anglo-American Oil Company sent to Europe “huge waves of oil” and millions of pounds sterling through its sale. To safeguard their interests this infamous Company engineered a military coup to depose the Qajar king and placed Colonel Reza Shah on the Peacock Throne. He made attempts to modernise Iran and granted a Constitution. The last thing the Anglo-American oil barons wanted was a modern Iran; they deposed him and enthroned his weak and incompetent son who strenuously supported Anglo-American oil interests.

That the discovery of such wealth in a country should be the harbinger of its misery is one of history’s tragic ironies. Neutral Western observers recorded the abysmal conditions in which Iranian workers lived in the big oil city of Abadan. Citizens of a sovereign state endured misery and injustice from foreigners.

Until 1953 West Asia was a conglomerate of oil-rich Arab nations that catered to the West. But the rise of Egyptian Gamal Abdel Nasser and the assassination of Iraqi King Faisal deeply worried the West.

Another turning point in Iran’s history came when the democratically-elected Mohammed Mossadegh became Prime Minister. Enraged by foreign depredations he took action to curb British and American plunder at the expense of the Iranian people.

President Truman supported Mossadegh; he was the voice of reason and progress, who wanted to strengthen democratic institutions and practices, who could reconcile Islam with modernity. Truman foresaw the disintegration that would follow a coup against Mossadegh and prophetically warned his compatriots: “Mishandling of the Iran crisis would be a disaster to the free world.”

Iran then stood at the crossroads; she could forge ahead as a modern secular state or sink back into poverty and oppression. But a dark destiny awaited her.

President Eisenhower approved Mossadegh’s removal. The legitimate and fiercely patriotic Iranian Prime minister was overthrown in 1953 by an Anglo-American coup called Operation Ajax because Mossadegh refused to countenance the ruthless exploitation of Iran’s wealth—as Chile’s Salvador Allende was deposed for the same reason, twenty years later.

The oil boom of the early seventies enriched Arab power elites and was supported by Western patrons. The paranoiac Shah, who had seen his father deposed, was unwilling to meet the same fate collaborated with Western oil interests at the expense of his own people. In return he had unwavering American support. He and his family members accumulated vast wealth and led lives of fabulous luxury. The Iranian ruling elite also thrived. Most Iranians were poor with little education and lesser opportunities to drag themselves out of abysmal misery.

By supporting the Shah’s dictatorship the United States of America alienated liberal Iranians who had looked to it for help in modernising Iran. This alienation provoked attacks on American citizens and installations in the early seventies. The USA became synonymous with the Shah’s oppression, the economic inequalities and social injustice. People lamented that the country with a rich intellectual heritage had become a police state where a murmur of protest against the Shah ended in imprisonment or mysterious disappearance. The sullen populace was controlled by suppression of freedom and harsh laws. The political parties—Peoples’ Mujahidin of Iran, Tudeh Communist and Socialist parties—were placed under stern surveillance. Any infraction by their members, even erroneously perceived, led to imprisonment without trial or unexplained disappearance.

The past casts long shadows over both men and nations; Iran’s past was about to catch up with the present through epochal changes.

The tinderbox was lit in October 1977 when Mustafa, son of the exiled cleric Ayatollah Khomeini, died. The dreaded secret police Savak was blamed for the death. When widespread demonstrations erupted, the Savak dispersed the crowds with live ammunition. The ensuing deaths of liberal leaders and demonstrators were also ascribed to the Savak and the ruthless militia. It was presumed that the display of brute force would stifle future protests. This only enraged the populace.

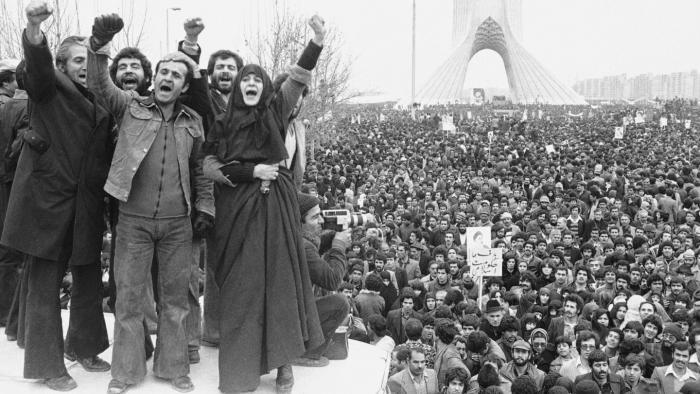

Image for representational use only.Image Courtesy : FT

Supported by the people, opposition came from the urban educated middle classes who wanted modern governance in accordance with the framework of the 1906 Constitution. The Islamic clergy or Ulema, which the Shah had suppressed, was not united in either their aims or their alliances. Sometimes they collaborated with the Islamists, at other times with liberals and even with Marxists of the banned Tudeh Party. Many thought that the protests were isolated outbursts and that the Shah could not be deposed. He had a standing modern army of 4,00,000 men and American military support. The necessary ingredients for a successful revolution were missing—defeat of the ruler’s army, a mutinous army and police force, revolt by the peasantry and proletariat, and a financial crisis.

Nevertheless, an undercurrent of resentment against the Shah gathered force. The mood of revolt intensified in ensuing months. There were protests on the streets, heated and secret discussions of discontent. Everyone resented the prevailing inequalities between the rulers and the ruled. They resented that benefits of the 1970’s oil boom went to the rulers instead of the people. The rising prices of essential commodities caused serious inflation and the purchasing power of people declined, making Iranians poorer.

Iranians expected liberals and socialists to lead the movement demanding equal rights, opportunities and incomes, and usher in a Western-style revolution. But the ideology for rebellion was provided by religious leaders who reviled the Shah for being a puppet of the West and for undermining Iran’s cultural and religious traditions. While Iranians chafed under restrictions, Westerners enjoyed privileges that were denied to them. The Shah’s folly of creating a single-party political monopoly with the corrupt Rastakhiz Party alienated the commercial classes.

In January 1978 there were ominous signs of revolt: strikes in factories organised by the communists and the socialists, and street demonstrations. Instead of the usual police methods to dispel crowds—plexiglass shields, water-cannon and tear gas—the police fired live ammunition and killed hundreds of protesters. The reign of terror further enraged the people. The pampered police and militia had never been trained to maintain law and order or to defend the nation. Their sole purpose was to maintain the Shah in absolute power through force.

Though the Ulema’s influence grew, the intelligentsia was confident that the clergy’s role would be ineffective as they had neither experience of modern governance nor ideas on economic development and social reform. Educated Iranians scoffed at the Islamist clergy; they were proud of their Zoroastrian past, of the Achaemenid and Safavid rulers who had nurtured great civilisations.

As the French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville observed: “...when a people which has put up with oppressive rule over long period without protest suddenly finds the government relaxing its pressure, it takes arms against it.”

Smouldering fury erupted into a mass movement in late 1978. But the opposition leadership slipped into clerical hands. At first, it seemed preposterous that a medieval clergy would attempt to govern a modern nation. The bizarre phenomenon of a theocracy in the twentieth century became possible through Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a Muslim cleric from the sacred city of Qom.

In 1963 Khomeini organised agitations against the Shah’s proposed White Revolution. This was unfortunate; at this time the Shah genuinely wanted to modernise Iran, introduce social and land reforms and reduce the power of the Muslim clergy, as Napoleon had curtailed the power of the Catholic Church. Afraid that these reforms would reduce the power of the Ulema, Khomeini declared that the Shah had embarked on the destruction of Islam in Iran. When riots began Khomeini was arrested and exiled in 1964. Living in the security of Neauphle-le-Château in France, he proclaimed his readiness to be martyred and reviled capitalists, communists, Western habits and customs and the modern ideas of economic and social progress.

In the meantime, discontent grew. Demonstrations and protests intensified in 1978 resulting in police violence. All sections of the population united in their opposition to the Shah’s regime. A general strike and mammoth protests in Iranian cities in October 1978 impacted the country’s economy adversely. The Ulema organised themselves. Regardless of the fact that they could be mowed down by a vicious militia, millions of Iranians protested on the streets. Though the new prime minister Jafar Sharif-Emami tried to introduce some freedom, Iran now moved inexorably towards revolution.

Unable to see imminent change, the American Security Adviser Zbigniew Brezenski assured the Shah in November 1978 that USA would maintain his regime.

Sensing the revolt, the opportunistic Iranian military and Savak gave covert aid to it. When the American ambassador William Sullivan suggested a military takeover, he was rebuffed and told that if Americans interfered in Iran, Americans there would be in danger. Seeing the nationwide opposition to the Shah’s rule, his staunchest ally, the USA told the Shah that he must go. Desperate, dying of cancer, the Shah and his family left Iran in January 1979.

Tehran burst into a festive mood. People marched through the streets carrying banners that announced end of a dark era.

Ayatollah Khomeini entered history on 1 February 1979. He left his French exile and arrived in Tehran on a chartered Air France flight. A surging crowd accorded Ayatollah Khomeini a tumultuous welcome in expression of their loyalty and veneration.

To demonstrate his disdain for power, Khomeini declined all posts but swiftly dismantled every feature of the Shah’s regime. He reappointed Mehdi Bazargan prime minister as he had been a prominent member of the opposition. Khomeini soon revealed his agenda by issuing a stern warning to Iranians that there would now be a government based on the Sharia: “Opposing this government means opposing the Sharia of Islam. Revolt against God’s government is a revolt against God. Revolt against God is blasphemy.”

By 10 February 1979, the Enghalabi Eslami was installed in Iran.

Though there was a universal reaction against a century of Anglo-American exploitation of Iran, liberals and professionals could not organise to lead a movement. The failure of secular forces brought the theocratic rule of the Ayatollahs, which changed Iran and heralded a resurgence of Islam.

Iran’s new rulers were anti-Western and terminated the military alliance with the US. Considering the possibility of installing a Leftist government, the Soviet Union made overtures to the new government. Any illusions on this were dispelled by the Islamic Republic’s harshness towards liberals, socialists and minorities. A medieval ideology was imposed on the eclectic Iranian people who had for many millennia contributed to mathematics, science, architecture and literature and who had assimilated many cultures.

The revolution in Iran seemed like a dialectical phenomenon—a reaction to the subordination to the West symbolised by the Shah and a cleansing process. While the US was afraid of loss of oil and a client state, Russia saw the larger implications of the Islamic Revolution; that it challenged secular values and incited cross-border religious fervour.

Once more, Iran was at the crossroads of history. Had the theocratic state promoted socio-economic progress, the events would have been different. But Islamic fundamentalism had a different code of conduct and values. Emphasis on religion was revived. The social and intellectual freedom for which thousands had given their lives during protests and demonstrations did not fructify.

Like the Christian crusaders, the Muslim clergy wanted to spread religious fervour beyond their frontiers. The mullahs played no small role in inciting Islamic fundamentalism in once-secular Afghanistan and in deposing a socialist government. Paradoxically, in this Iran and the US had a common aim; the Ulema who scoffed at socialism and America, which wanted to undermine a pro-Russian government. The so-called Mujahidin had patrons both in Iran and the US.

To punish a resilient Iran and undermine her strength, the US aided Iraq in a terrible eight-year war that ravaged both nations. But when President Saddam Hussein displayed independence—despite opposition from the United Nations and mammoth street protests by millions of Americans, Britons, French and Germans—the Bush-Blair duo invaded and ravaged Iraq. Even after seventeen years, no weapons of mass destruction have been found. But her oil still flows. Bush and Blair did not bring democracy to Iraq; they turned a stable secular Iraq into a war-ravaged state where the furious remnants of Saddam Hussain’s army have formed the ISIS. And an army of occupation is in Iraq.

Perhaps it was this scenario that prompted US President Barack Obama, together with Russia, Britain, France, Germany and China, to halt the deterioration of relations with Iran by formulating the Iran nuclear deal. These states wanted to lift sanctions so that Iran could become a stable state and not a potential dangerous foe. The leaders of these nations had the wisdom to realise that West Asia was a turbulent region with numerous warring factions armed with nuclear weapons and that one episode could endanger not only West Asia but could spill beyond its frontiers with catastrophic consequences for the world.

The incumbent US President Donald Trump nullified that agreement with Iran without assent or approval of the other signatories. While flirting with North Korea’s rocket man, he took punitive measures against Iran. Numerous sanctions were inflicted on Iran which adversely affected its citizens. Legatee of ancient civilisations and of resilient character, Iran spread her influence in West Asia.

As Iran’s influence spread in the region, Trump ordered the assassination of Iran’s hero and commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, Major General Qasem Soleimani. It was an arrow through the heart of the IRG. General Soleimani and his army had vanquished the Islamic state in Iraq and Syria. Many Americans condemned the unjustified killing. The Furies which seem to now preside over Iran’s destiny decided that this blow was not enough. Something more was needed. So a disastrous mistake was made by shooting down a Ukrainian civilian plane carrying passengers. The initial concealment infuriated Iranians resulting in widespread protests.

President Trump stoked the flames and offered support to the protesters. Many Iranians responded by reminding him of the sanctions he has imposed on their country which have caused them acute economic hardship. Others tore down photos of General Soleimani.

It is difficult to predict the future of Iran, which is facing economic stress and the hostility of a superpower. Britain, France and Germany have now initiated a dispute mechanism which complicates the situation. Encountering all this, Ayatollah Khamenei made a rare public appearance and spoke at Friday prayers on 17 January, admitting the need for some changes but also advising Iranians to remain loyal to their country.

Indians, legatees of great civilisations, feel sympathy for Iran whose history has been as splendid and as turbulent as ours. While wishing the Iranians peace and prosperity it is everyone’s hope that this great nation forges forward in achievements and not backwards into restrictive burdens of the past.

Perhaps Firdausi would agree.

The author is a retired civil servant and writes on international history. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.