Bigotry, Corruption, Fake News and Patriarchy: Pataal Lok Mirrors India

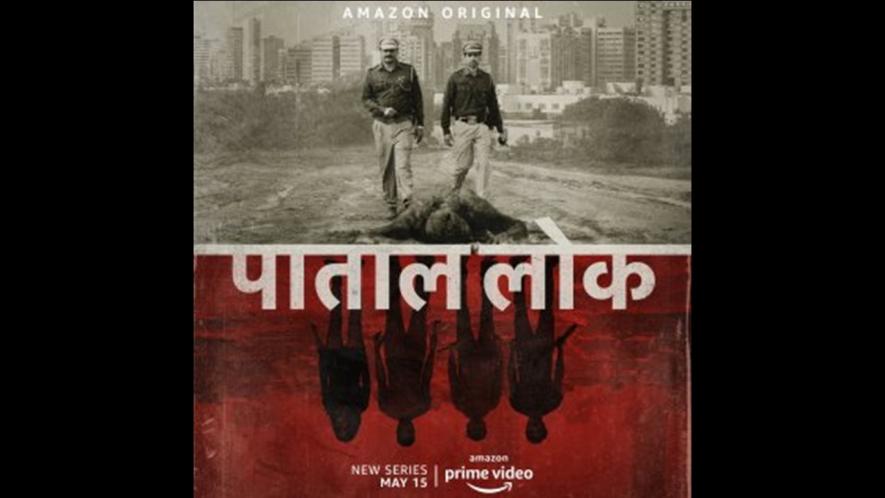

Patal Lok poster. | Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

Pataal Lok, the story of an investigation into a conspiracy to assassinate a prominent journalist directed by Sudip Sharma, is a stunning reflection of the socio-political climate in India. The series, (playing on Amazon Prime), opens with a jibe on how gullible people are to WhatsApp forwards. The main character, a low-ranked police officer named Hathiram Chaudhary (played by Jaideep Ahlawat), narrates the concept of swarg lok, dharti lok and paatal lok—heaven, earth, and the netherworld—to his collogues and says, “Waisey to yeh shastro me likha hai, par maine WhatsApp par padha—all this is written in our scriptures, but I read about it on WhatsApp.”

The plot begins as a Delhi Police team arrests four men in connection with the conspiracy to kill Sanjeev Mehra (Neeraj Kabi), a prominent journalist and editor of a news channel. The four accused are Tope Singh (Jagjeet Sandhu), Kabir M (Aasif Khan), Mary Lyngdoh or “Cheeni” (Mairembam Ronaldo Singh), and Vishal Tyagi (Abhishek Banerjee).

The investigation is assigned to Hathiram, who is assisted by his subordinate, Imran Ansari (Ishwak Singh). Ansari is an aspiring IPS officer who clears the UPSC mains later in the series. Hathiram, who is frustrated with his stagnant career prospects, sees in the high-profile case his only opportunity for a promotion. The case brings some thrill and meaning into his otherwise monotonous work-life.

The series confronts bigotry and discrimination against Muslims mainly through the character of Ansari. Even though Hathiram is portrayed as a “tolerant” person, who is on great terms with his Muslim subordinate, he uses derogatory terms while interrogating Kabir, the only Muslim accused. It underscores how the vocabulary of bigotry and indignity, when normalised, enters living rooms, bedrooms, and then the minds of even so-called tolerant people such as Hathiram. Ansari is visibly uncomfortable by the tone of the interrogation, and Hathiram apologises for this later.

The case in the series, like cases in real life, is eventually transferred to the CBI, which implicates Kabir and others in a larger “jihadi” terrorist plot. Having worked on the case earlier, Hathiram and Ansari realise that the CBI’s claims are riddled with loopholes. (Again, no surprise.) Hathiram discovers that senior officers in the Delhi Police had staged the entire crime on the direction of an influential politician. The extent to which corruption and compromise bedevil the investigative agencies should also not be a revelation for most viewers.

Ansari is one of the most sincere officers at the police station, yet any mistake he makes is casually attributed to his religious identity—usually behind his back, but sometimes on his face as well. Some forms of subtle harassment are also highlighted: for example, when Ansari dozes off, having worked late into the night on the case, his colleagues (Hathiram not included) start ringing a bell near the Hindu deity in the police station a little extra-loudly, which wakes him up.

The subtle and overt ‘Otherisation’ of Muslims and prejudice against the community is captured in many other instances. On finding out that Ansari has cleared the UPSC mains, a CBI officer congratulates him and says, “Aajkal inki community se kaafi aa rahe hain na? Dekhna, isse inki community ki image apne aap hi change ho jayegi—a lot of people from their community are now making it. This will change their image.” The implication is that there is something wrong with the Muslims, which needs to be “fixed” and the onus of doing so is on the Muslims.

It does not end there. During a mock interview, Ansari honestly answers a question about the changing state of minorities in India in the last few years, saying that he believes that they have been feeling more threatened of late. However, he was advised to tackle those questions with much more care, and asked to display a more “positive” attitude. Later, he recounts the incident and observes that Muslims are accepted by the system only when they qualify the prerequisites of being “positive” and “progressive”, the yardsticks for which are conceived by the majority, and its terms set especially for them. Even upward social mobility for Muslims comes with terms and conditions.

It seems that Ansari loses the zeal he initially had for UPSC as a result of all this. Through his character, the series highlights how it is problematic to set different standards for Muslims. His visible discomfort over bigoted remarks also goes to show that no matter how “minor” or “casual” people think their comments are, they have a huge effect on the self-respect of a person who is on their receiving end.

By going into the back story of Tope Singh, the series shows that the accused is himself a victim. Belonging to a “lower” caste from a village in Punjab, he was bullied and harassed by people from elite castes. One day, fed up with the harassment, he stabs three of them to death—thus entering the world of crime. On the other hand, caste-based endowments and support structures in Chitrakoot, the native place of Tyagi, show the hugely important role played by caste in deciding the dignity and quality of life of a person.

Hathiram, who portrays the lower middle class strata, struggles with the English language. His son, enrolled in an elite school in Delhi—he was admitted on the police commissioner’s recommendation—is often bullied and humiliated by his bourgeois classmates and other students. But his friends outside the school also make fun of him, for being “English-medium”. Hathiram’s son embodies a peculiar class struggle; he is either viewed as someone “sub-standard” (such as by his schoolmates), or as one who is trying to punch above his weight (by his peers and others).

Patriarchy, too, is a running theme in the show. All women, irrespective of their position in society, have been shown as victims of patriarchy. Some, such as Hathiram’s wife, are “unequal” in a more conventional sense—she does all the chores, takes care of the family, is often mistreated by her husband. Others, such as the journalist Sara (Niharika Lyra Dutt), are discriminated against more subtly—they are structurally oppressed by a system in which positions of power are occupied by men. The series also touches on the ordeal of Cheeni as a transwoman: from her childhood sexual abuse to her discomfort at being thrown into the male ward in prison.

Now consider the professional life of Sanjeev Mehra, the TV man. Here the series brings up the issue of corruption and the media’s compromises with ethics of the profession. Mehra is under pressure from the main stakeholder of the channel. He is on the verge of being fired, as the viewership and popularity of his channel—particularly his prime-time show—are declining. He manages to regain his popularity by juicing up the story of his own attempted assassination, by exaggerating it into a “threat to the nation”. His professional “stability” comes at the cost of his liberal principles and at the cost of journalistic ethics. Who can deny that this is the story of mainstream journalism currently being practised in India?

Yet the series is very subtle; it does not spoon-feed the audience on what is good or bad and rather presupposes that bigotry, patriarchy, etc. are bad and yet prevalent in society (all characters end up losing something as a result of this corrupt order). Through the backstories of the accused, the show tries to underscore that it is not individuals who are “good” or “bad”, but their experiences of being discriminated against or humiliated that usually turns them into what they become. By showing bigotry, corruption, the media’s compromises, patriarchy, caste and class struggles, Pataal Lok has taken on a portrayal of present-day India that we rarely see on the small screen.

The author studies political science at Ashoka University. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.