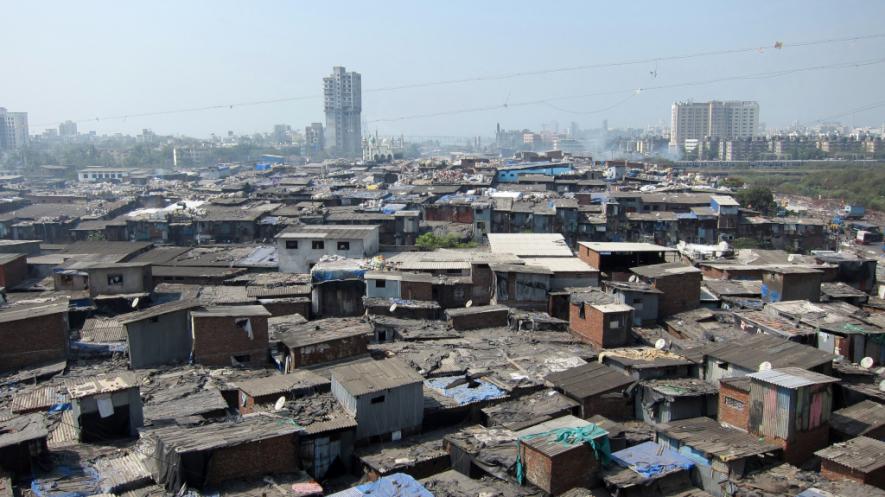

A Housing Rethink is Needed: Learn From Those Who Make Their Own

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Imagine a community, in existence for over a century, that creates its homes from salvaged materials, recycles much of the surrounding city’s waste, produces upwards of $1 billion in economic output and has done all of this while being marginalised, neglected and exploited by powerful political and economic actors.

I am, of course, talking about the Dharavi ‘slum’ in Mumbai, but similar conurbations exist in cities across the world. For decades now, successive governments have struggled to know ‘what to do’ with places like Dharavi and with those that call it home. In Mumbai, several government schemes over the past 50 years have been unsuccessful in addressing Dharavi’s problems. Some have sought to remove it, some upgrade it and most recently to squash it into tall high-rises. None have asked the question, what can we learn from it?

“We have seen the failure of Master Plans and their estimations as well as their inability to implement many of their mandates,” says Sameep Padora of sP+a architects, which has sought to reposition settlements like Dharavi as “potential model for affordable housing within the city”, rather than a problem to be solved. “Incremental urbanism coupled with loose framework plans could be the counterpoint to traditional forms of planning, especially in contexts like India,” he adds.

Incremental urbanism is, in short, the process whereby people make ad-hoc and small scale adjustments or extensions to buildings over time, depending on the resources, space, skills and equipment available. While such actions may seem piece-meal or unplanned, they actually result in a rich array of building types and uses. Incremental urbanism, participatory planning, recycled construction materials, a focus on overall space rather than floor space, and the ability to adjust buildings to prevailing climatic and economic conditions are just some of the ways in which we can learn from slum housing.

The intention here is not to romanticise or obfuscate the conditions within informal housing settlements—they face myriad problems from sanitation, healthcare, educational opportunities and infrastructure. And furthermore, the perception of slum settlements as “poor but happy” conglomerations, reinforced by pervasive ‘slum tours’, needs to be challenged. But what can we learn from such forms of incremental urbanism that can then help inform future housing policy?

“From an architectural point of view, these are impressive structures,” says Pinkish Shah, of award-winning S+PS Architects in Mumbai. He sees them as an incremental process that is attuned to the needs of residents and develops over time. “We have seen that people have the ability to make changes in their homes. We’ve seen homes that have grown a story. They have gone from ‘kutcha’ (temporary) to ‘pukka’ (permanent),” he explains. “And then over time they get washing machines and ACs, so people have the resources and abilities—they’ve just not been able to break into the formal networks where finance and rights are accessible to them.”

“We’ve misread them in many ways and that’s really sad in terms of policy—to not really see the true potential,” he adds.

Padora agrees and argues that the nature of slums means that every construction is rigorously assessed in terms of what it provides to the individual or community. “The frugality of resources, whether land or finance, that slum dwellers are faced with, not to mention issues of tenure, creates an ecology where every aspect of what they build, whether house or neighbourhood, is subject to its performance.”

This efficient use of resources, high levels of community engagement and clear performance criteria for new constructions results in a process that has more accountability and transparency than many high-end construction projects, which are often intentionally opaque in terms of funding and ownership.

Moreover, “incremental urbanism can be a lot more light-handed and responsive, and can operate in shorter time spans,” says Padora. A more reactive form of housing construction offers increased flexibility and the ability to adapt to changing conditions, be they climatic or economic. However, “their potential can only be unlocked and scaled up if regulatory frameworks acknowledge the relevance of this kind of urbanisation and make allowances for building codes and city plans to incorporate these new and hybrid forms of settlement,” he adds.

Hussain Indorewala, educator and urban researcher at Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture (KRVIA) highlights how, ironically, many of the city’s middle class inhabitants, who lament the presence of slums in the city, actually enjoy the benefits of such loose frameworks and relaxed building codes—middle class apartment blocks and gated communities often deviate from planning norms, acquire land dubiously and circumvent building regulations, yet are still seen as part of the ‘formal’ housing sector.

The idea of housing as being made from scratch, a widespread and typically accepted idea in architecture, needs to be challenged in favour of seeing it as an iterative process. Architects should “develop new ways of thinking about housing and develop the conceptual, institutional and technical tools that can help improve already existing settlements—upgradation and retrofit—rather than think of housing as something that they have to conceive from a scratch,” says Indorewala.

He says housing should be seen as “a process (a verb), and not a thing (a noun)” and that architects should view it as a right, rather than a commodity. “Achieving good living environments is not simply about making idealised plans,” he explains, “but often about providing the necessary infrastructure for settlements to grow and change with time.”

Home-grown and negotiated strategies for organising space are in high demand given that fewer than one in 10 families in Mumbai can afford to buy a house, according to the National Institute of Urban Affairs. Therefore, there is not only the demand but also the need for a different form of housing provision—one that caters to the majority of its residents.

“Unfortunately, Mumbai has become this golden goose for real estate developers and there is such a glut of provision in the high-end housing market,” says Shah. “I think the city authorities assume slum dwellers don’t exist, but more than half of our population reside in slums. We seem to want to wish it away.”

India faces a stark choice in the coming years. Continue to leave the provision of ‘formal’ housing to the private sector or adopt new strategies and ways of thinking that could empower individuals and communities to organise and create their own homes. The former has clearly not worked for most residents in cities like Mumbai. Maybe it is time authorities looked closer at the latter.

Recognising the importance of incremental urbanism to people and relaxing some of the codes around it in the right places is a start, but there also needs to be a fundamental rethink of how we see housing. Within the trinity Roti, Kapda aur Makaan, the only ambiguous part is Makaan. Shelter takes many forms and protects against a variety of conditions, and this must be recognised by city authorities when they make decisions on housing. A penthouse in south Bombay and a shack in Dharavi: both are Makaan.

The author is a freelance journalist with an interest in how geography, housing and architecture reflect and reform social relations in the city. He has written on slums, smart cities and traditional design in the Indian context.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.