CAA/NRC: India’s Credibility Crisis Is Only Getting Worse

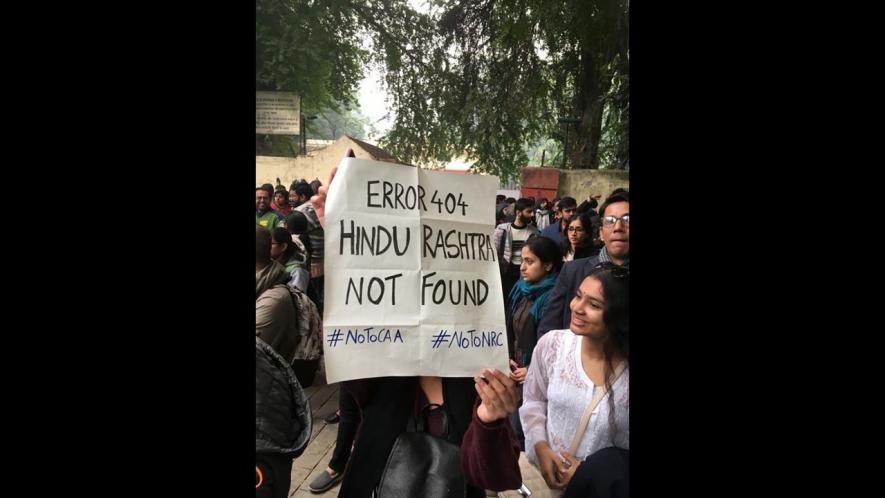

A protester holds a placard during anti-CAA-NRC protest in New Delhi. | Image Courtesy: Twitter

The Ministry of External Affairs is on overdrive. Last week, it released a statement saying its missions abroad had conveyed to authorities in different countries that the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019, and National Register of Citizens (NRC) were matters internal to India and, in any case were meant to expedite the grant of citizenship status to persecuted minorities.

It also told the Lok Sabha on Wednesday that the Union government’s proactive outreach to the international community iterating that the abrogation of Article 370 and the bifurcation and downsizing of Jammu and Kashmir into two Union Territories instead of one state, were also an ‘internal’ matter, to counter Pakistan’s campaign on the issue, had been received favourably, with several countries agreeing with India’s position.

The regime now in power is run by people who are in many ways hard-headed realists, which is a polite way of saying that many of them display clear signs of an enhanced sense of ruthlessness and amorality that borders on psychopathology, which gets more intense, the higher you go. But in many ways, the leadership of the regime either lives in a world of fantasy because their constant recourse to falsehood, otherwise called propaganda, blinds them to reality.

The reality is that India’s reputation as a constitutional democracy has taken a savage beating as well it might, given that the current regime has inaugurated a police state by subverting constitutional guarantees and sabotaging institutional integrity. We are on the verge of becoming a fascist state. And members of the international community are calling the regime out.

We may well say, for instance, that the United States, with its appalling human rights record generally speaking, but especially under Donald Trump, is hardly in a position to point a finger. True. That does not, however, make the charges against the regime go away. They remain equally true.

Let us look at the recent record going backwards chronologically. On Monday, the city council of Seattle, the largest city in the state of Washington, unanimously passed a resolution, sponsored by an American of Indian descent, against the CAA and NRC because they were ‘discriminatory to Muslims, oppressed castes, women, indigenous…people’. Just a bunch of coastal liberals in the United States, you could well say; of no great importance.

On 29 January 2020, however, the US Congress was briefed on the situation in India in connection with the CAA and NRC by human rights groups. An Indian human rights activist, Dr Sandeep Pandey recounted the persecution of anti-CAA/NRC activists being carried out by the regime. He had been placed under house arrest and countless other activists had been persecuted. He also told the US Congress that Muslims were being targeted in Uttar Pradesh, brutalities were being committed on students and the regime was following a policy of communalisation and polarisation. “It is a politics of divisiveness, polarisation and communalisation for political gains. The government has become an enemy to a segment of the population, Muslims and people who don’t agree with its views,” he concluded. Seattle might not be a big deal, but the US Congress probably is.

A few days before this, a resolution that was sharply critical of the CAA, calling it “discriminatory in nature and deeply divisive”, was tabled in the European Parliament for a debate and a vote. It seemed to have overwhelming support, though the European Union (EU) itself distanced itself from the resolution. The vote was postponed to March, in view of, inter alia, an upcoming summit meeting between India and the European Union, for which Prime Minister Narendra Modi will visit Brussels and the pendency of suits against the Act in the Supreme Court.

On 23 January, billionaire investor George Soros had some harsh words to say in Davos about India, alongside the US, Russia and China. “Nationalism, far from being reversed made headway. The biggest and most frightening shock came from India where a democratically elected Narendra Modi is creating a Hindu nationalistic state, imposing punitive measures on Kashmir…and threatening to deprive millions of Muslims of their citizenship.”

On the same day, The Economist cover declared, “Intolerant India. How Modi is endangering the world’s biggest democracy.” The cover story said the Modi government was turning India into a Hindu state and was building detention camps to house people rendered stateless by the CAA and population registers.

On 22 January, the Economist Intelligence Unit released its global democracy rankings for 2019. India had fallen ten places on the table, its score falling below seven for the first time since the rankings were instituted in 2006. India had always been categorised as a “flawed democracy”, meaning that though it had free and fair elections and basic civil liberties, there were weaknesses with regard to governance, political culture and people’s participation. India was among 11 countries which fell in the rankings. Its position is now 51 and score 6.90, down from 7.23. The main reasons for this was stated to be an erosion in civil liberties in the shape of the scrapping of Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomous status, and the CAA and NRC, which, it was noted, was alleged to have targeted Muslims.

In December last year, the UN Human Rights Commission (UNHRC) had characterised the CAA as being “fundamentally discriminatory”, as well. In September, it had expressed concern over the curbs imposed on Kashmir, a polite way of describing lock-down enforced by an army of occupation.

These are neither bleeding-heart liberals nor loony lefties. We are talking about bodies like the UNHRC and the US Congress and a conservative media organisation like the Economist, on the one hand, and a man like Soros, on the other. Parroting the internal matter line will not help wish away the erosion of credibility. In any case, the CAA/NCR is not exclusively a matter of internal concern, for two reasons. One, if people in Assam, Bengal and Tripura are deprived of citizenship on a large-scale, it will have an impact on Bangladesh, because, while a large number of people may be rendered stateless and bundled into hideous panopticons, a large number are also likely to be pushed into Bangladesh.

India’s dwarfed neighbour has not protested because it cannot given geopolitical realities, but it has signalled its apprehensions and displeasure, with Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina saying the CAA and NRC were unnecessary.

Furthermore, India says the CAA has the humanitarian goal of giving shelter to persecuted minorities—which is a lie given that the body of the CAA does not mention this goal and many senior BJP leaders have said that grant of citizenship will be on a case-by-case basis because in many cases it would be extremely difficult to prove that a person had indeed been persecuted. The actual reason as we all know is promoting polarisation and trying to pander to the BJP’s fundamentalist Hindu vote-bank.

Just making this argument, however, constitutes meddling into the ‘internal affairs’ of Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Who gave the Indian government the right to decide who is being persecuted in whatever country? If India’s tinpot despotic regime can make such imputations, surely other countries can make similar imputations against it with respect to its persecuted minorities. The evidence is out there, in bucket-loads. India has been accused of interference, for instance, by what Indians may consider an unlikely source. Minority groups in Pakistan—Christians, Hindus and Sikhs—have rejected the CAA as a divisive tool in the hands of the Indian regime. The Pakistan Hindu Council has rejected the Act and Pakistan’s Hindu leaders have called it the “hatred” law, against Pakistan and against minorities in both India and Pakistan.

It can be argued that the minorities are saying these so as not to fall foul of the establishment. That could be true of both Pakistan and India. It still does not give India the right to interfere in the affairs of its neighbours. What Delhi’s regime must do, but will not because it is authoritarian bordering on fascist, is restore India’s constitutional democracy, however flawed. Or, one hopes, the people will.

The author is a freelance journalist and researcher. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.