Coronavirus is Scary: Your Biases Make it Feel Worse

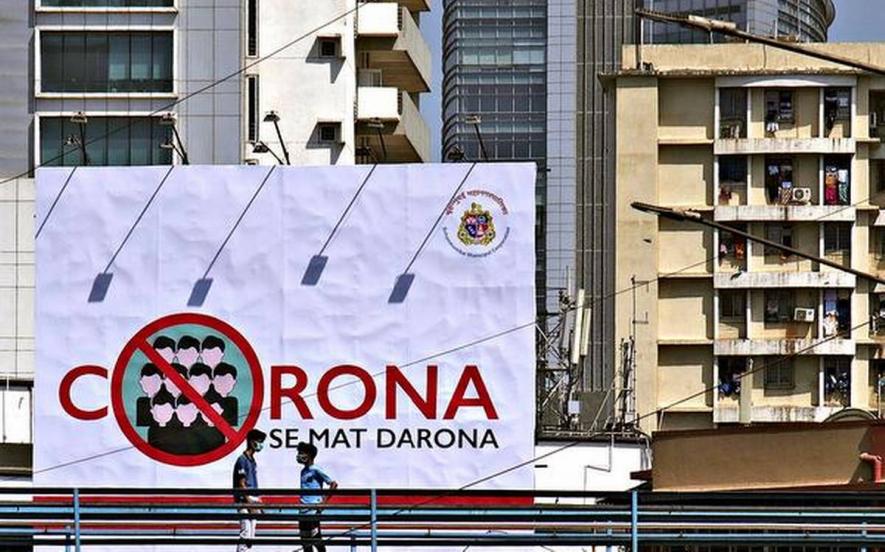

Representational image. | Image Courtesy: The Hindu

Suspended over a road rolling out of Delhi’s Vasant Kunj colony is a billboard featuring microscopic images of the Novel Coronavirus painted in white against a crimson red background. Embossed on it is the line, “Don’t Panic, Take Precautions!” The visualiser of the billboard seems to accept as natural that the Novel Coronavirus will throw citizens into panic and tries to divert them towards taking precautions instead.

David P Ropeik, a former instructor in Risk Communication at the Harvard School of Public Health and author of the book, How Risky is it, Really? Why Our Fears Don’t Always Match the Facts, said to us, “‘Panic’ is too strong a word to describe how people [across the world] have reacted to Covid-19, [the illness caused by the Novel Coronavirus]. Fearful certainly, but not running about wildly. Society did not break into chaos.”

Yet visuals from the national lockdown did conform, at times, to Ropeik’s definition of panic. Thousands upon thousands of migrant labourers defied the lockdown to trudge home hundreds of miles away. Scores died during the exodus from cities. Their travails, ultimately, compelled the Union government to arrange transport for them, staving off what might have led to a societal meltdown.

We may not be in panic mode, but scared we certainly are. This is partly because of the timing of the lockdown, which was imposed nationwide on 24 March, when India had just 536 Covid-19 cases. This framed the virus as an invisible killer waiting to pounce upon every human. India entered Unlock-I on 1 June, by which date the cases had multiplied to 1.98 lakh.

The message this conveyed was that the government had failed to check the spread of the virus. It fanned anxieties all around, compounded further by poor public communication—of which the billboard in Vasant Kunj is an example. An even more telling example was Prime Minister Narendra Modi telling the nation in his 24 March address that the Coronavirus could be vanquished in 21 days.

The lockdown was supposed to provide the government a head-start to repair and augment the broken public health infrastructure, before Covid-19 infections grew exponentially. It was supposed to bring down the virus’s basic reproduction number, or RO, which is an estimate of the number of people one patient could infect. The RO slid from 1.83 between 4 March and 11 April to1.22 on 4 June. An RO above 1 means the infection still remains highly contagious. The RO in India ranges from 1.03 in Uttarakhand to a high of 7.92 in Bihar.

The slide in RO may be encouraging, but this cannot be said of the health facilities, which still remain too shambolic to inspire confidence in people. They fear contracting the Coronavirus as much as they dread that if they were to fall ill, they would be denied prompt medical attention. This has spawned a feeling of helplessness among us.

Helplessness always breeds anxiety and fear in people. Our helplessness is our own creation.

“I have coined a new term for what we have been made to experience—Anthropescenity,” said Dr Anurag Mishra, founder of Psychoanalysis India. Anthropescenity is a creative combination of the words “Anthropocene”, the current geological age during which human activity has had a dominant influence on climate, and “obscenity”. “Anthropescenity means obscenity arising out of human stupidity,” Mishra said.

One of our incredible stupidities was to impose the lockdown at an early stage in our tryst with the Coronavirus. Isolation is considered the most effective instrument, in the absence of vaccination, to check an epidemic. We exhausted our firepower, so to speak, long before the Coronavirus graph started its steep northward climb.

“We needed to lockdown the virus, not the people,” Mishra said. “The only way to lockdown the virus, once we knew it was spreading around the world, was to emphasise the wearing of face masks.” He said the advent of HIV, a virus transmitted by the mingling of body fluids during sex, made the use of condoms widespread. Likewise, the human lung and its vicinity is where the Novel Coronavirus replicates, and every person needs to wear a mask to ensure he or she does not infect others. “Face mask is the new condom,” Mishra said.

These factors have created conducive conditions for the germs of fear to thrive and grow. Yet, fear also involves humans assessing the risks they take in any situation. American psychologists Paul Slovic and Baruch Fischhoff have shown that risk is a feeling—that our fears are not so much an outcome of our objective analysis of facts, but how these facts feel to us.

Covid-19 versus road accidents

On the face of it, the facts regarding the Coronavirus in India are not as menacing as they feel. Column 5 of Table I shows that only 28 persons per every lakh run the risk of contracting the virus. The figure for India is higher than for West Bengal, but lower than for Delhi, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat.

The Coronavirus infection does not necessarily kill the person who has contracted it. As of now, death for every lakh of persons (Column 4, Table I) because of Covid-19 is a mere 0.82. This figure plunges for Tamil Nadu and West Bengal.

A person forms his or her sense of the risk or vulnerability by comparison. India is not a middle class country; the ownership of vehicles here is still limited. Yet, as Table II shows, the risk of accident that every Indian faces is higher than what he or she does from the Coronavirus. Thirty eight persons per every lakh of citizens met with an accident in 2018, as against 28 contracting the Coronavirus.

In 2018, 1.51 lakh people died in road accidents. Or, to put it another way, 12 persons out of every lakh Indians perished on the road. India’s Coronavirus fatalities are still a long way away from catching up with the death toll in accidents.

Yet few Indians shy away from hitting the highway, even after witnessing battered cars and trucks turned turtle. They do not shy away, as Slovic and others have shown, because they feel they are skilful drivers. Once they grip the steering wheel they feel they are in control of their destiny.

After terrorists crashed aircraft into the World Trade Centre in New York on 11 September 2001, domestic air travel in the United States was down 8.7% in May 2002 compared with the previous year, say George M Gray and Ropeik in their paper, “Dealing With the Dangers of Fear”. A good many Americans took to driving instead of flying from one city to another. Data showed that between 700 and 1,000 more people died in motor vehicle crashes from October through December of 2001 than during the same three months the year before.

Stress can bust you:

The fear of Indians regarding the Coronavirus could prove inimical to them. Fear releases hormones such as adrenaline, norepinephrine, and cortisol in humans. “If we are chronically more worried than normal, that suppresses our immune system. That is not what we want with the germ spreading around,” Ropeik said.

So excessive worrying about catching the bug could make you even more vulnerable to the virus, especially if you have a pre-existing heart ailment. The fear of venturing outside could also have you adopt a sedentary lifestyle, a no-no for those who have hypertension.

The location of a person could also determine his or her levels of fear. Table III shows the total cases and deaths per lakh of population for Chennai, Mumbai, Ahmedabad and Kolkata are far higher than in the states in which these cities are located. Delhi’s is far higher than India’s. These cities are densely populated, creating a fertile ground for the Coronavirus to spread. Their residents are likely to be relatively more scared than those who live in towns that have not witnessed inbound migration and are thinly populated.

Cities that are economically or politically important generally have greater concentration of news media. All five cities in Table III have been in the media spotlight. “Media coverage raises awareness everywhere, which raises fear to some degree,” Ropeik said. “But news of what is happening in one place does not automatically make people elsewhere greatly afraid. In fact, when risk is occurring elsewhere we tend to tell ourselves, ‘Well, at least it is not happening here.’”

In other words, people are scared when they personally feel at risk.

Covid-19 versus tuberculosis:

Our fear of road accidents is mitigated by our belief in our driving skills. We do not seem to have such a shield against the risk of contracting tuberculosis, which is counted among India’s major killer-germs. Take a look at Table IV.

The incidence of tuberculosis for every lakh of Indians (Column 4, Table IV) is far higher than the number of Coronavirus cases on the same scale—178 against 28.35. Divide the total number of deaths (Column 5) by 365 days of the year and you will be stunned to know that 1,232 Indians died of tuberculosis every day in 2018.

So why did tuberculosis deaths fail to grab media headlines? For one, other than Kolkata, the tuberculosis cases per lakh of people are far lower than the Coronavirus cases in the five cities listed in Table III. Urban centres doubling up as media hubs dominate news. They did not think deaths outside the urban centre were worthy of coverage. Besides, the RO for tuberculosis was 0.92 between 2006 and 2011. RO below 1 for any infection means it is no longer alarmingly contagious.

Yet, death due to tuberculosis significantly outstrips death due to Coronavirus. India reported its first death due to Covid-19 on 12 March, in Karnataka. On 16 June, the death tally stood at 9,900 (Column 1, Table I), which means roughly 111 people have been dying of Covid-19 every day since 12 March, nowhere near the victims tuberculosis claimed in 2018.

Tuberculosis does not worry us because it has been around for decades. For instance, the founding members of the Tuberculosis Association of India comprised Lord Linlithgow, who was the governor general and viceroy in British India between 1936 and 1943. Humans do not tend to fear what they are familiar with.

The Association’s FAQ says that because tuberculosis is an infectious disease, the person suffering from it should cover their mouth with cloth while coughing or sneezing. Sounds familiar, does it not? Yet tuberculosis is not feared also because it has a cure. The Association’s website says, “When a patient starts treatment, then after about two months he or she becomes non-infectious.”

By contrast, most Indians likely heard of the Novel Coronavirus in December and January, and did not even then fathom the danger it poses. Its treatment still involves a hit-and-trial method. We are not even certain that a person cured of Covid-19 becomes immune to it. Death in Coronavirus cases can be swift. A routine cough can become a desperate gasp for air in just a day or two. A Coronavirus-infected is dependent on chance for his or her cure. And chance makes us nervous. For a religious country such as India, chance prompts people to “petition the Lord with prayer” for their safety.

But it is also true that we do not obsess about tuberculosis because the incidence of it in the middle class is low. A World Bank study quotes the World Health Organisation to say, “TB is a disease of poverty.” That is because “poor nutrition and an inadequate diet weaken the immune system and increase the chances of infection and developing active TB.”

It is likely that TB, despite its high death rate per lakh of people, has not become India’s obsession because the middle class, which dominates all narratives and prioritises national issues, is relatively insulated from it.

Death by drinking, smoking:

Every packet of cigarettes manufactured in India has to carry the mandatory warning: “Tobacco Causes Painful Death.” Every packet features an image of cancerous protuberance on the neck, so ghastly that the inveterate smoker will likely close his eyes to relish a smoke.

Table V shows death by tobacco is as high as 77 persons per lakh of population. This figure includes cigarettes and other forms of tobacco use. In fact, 9.37 lakh died because of tobacco abuse in 2018, a figure the Coronavirus fatalities will not touch, judging from worldwide trends.

In contrast to smoking, death due to drinking alcohol is relatively lower. Nearly 2.6 lakh people die due to ailments caused by excessive drinking, as Table VI shows.

Yet smokers and alcoholics do not kick their addiction, because death is a possibility in the distant future, around the time they would be old and waiting in the “departure lounge of life,” to quote a phrase the late lawyer Ram Jethmalani often used. Ropeik provides a fresh perspective on the smoker’s apparent disdain for death: “Four out of five smokers try to quit. They recognise the risk but their addiction overrides their fears.”

Strong identification with social issues can have people overcome their fear of death, in the same manner as the craving for nicotine does in a smoker. Take the mass protest against the death of George Flyod in the United States. Thousands upon thousands swept aside their fear of contracting Covid-19 to pour out on the streets there to protest against racism.

Ropeik said, “For those who joined public protests, the brutality of the video [showing a policeman choking Flyod to death], on top of pre-existing emotions about racist police, on top of how anxious and emotionally raw people were because of Covid, had much more power than the fear of the disease.”

Or desperation could become an antidote to fear. For instance, the failure to find work and earn a livelihood in cities turned lakhs so desperate in India that they openly flouted the curfew code of the lockdown to go home.

Both Mishra and Ropeik say people are more sensitive about risks that are catastrophic than those that are chronic. It triggers a feeling of awe in them. Fear of the Unknown is a dominant human emotion. From this perspective, it is understandable for Indians to be scared of the Coronavirus.

But they do themselves harm by worrying excessively, as it would suppress their immune system at the time they need it to work efficiently. What is excessive is, of course, subjective. Yet there are telltale indicators of excessive fear: Does your heartbeat race every time you think of the Coronavirus? Have you become obsessive about tracking Coronavirus cases and information? Do you become nervous every time your throat itches or you sneeze? Do you feel like a warrior going to a battle every time you step outside? Yes. You need to get a grip.

The government too needs to get its messaging right and ensure people are not unduly scared. For starters, they need to change the line on the billboard in Vasant Kunj. For instance it could say, “Chill and Take Precautions.” And replace the images of the virus against a crimson background, for those seem like creatures from the netherworld in search of a prey.

Ajaz Ashraf is an independent journalist and Vignesh Karthik KR is a PhD student at King’s India Institute, King’s College, London. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.